By Anne M. Filiaci, Ph.D.

DEVELOPING A THEORY: EARLY LIFE, EDUCATION, INFLUENCES, 1874-1898

On January 1, 1898, the New York state legislature consolidated New York City into a single entity that included Manhattan, the Bronx, Brooklyn (Kings County), Staten Island (Richmond County), Long Island City, and a good portion of Queens County. This law also unified all of the area’s public schools into one system. William H. Maxwell, who had been Brooklyn’s school superintendent for over a decade, was elected to serve as the Superintendent for the expanded New York City school system in 1898.

The consolidation took place during a period when large-scale immigration was already straining the City’s public school resources. Compulsory education laws (no matter how badly enforced) added to the burden. Children who would not normally be in school were now expected to attend. There simply weren’t enough teachers or buildings to accommodate the large numbers of new students. Some schools adopted half-day sessions to double the number of students taught, while others simply turned thousands away.

Compulsory education laws also presented a multitude of other challenges to teachers. A single overcrowded classroom often included students from many different cultural backgrounds, some of whom were not fluent in English. Teachers also faced problems educating students of varying skill levels simultaneously. This task was made even more difficult because so many who found it difficult to learn in a traditional classroom setting were now attending school for the first time.

Lillian Wald became involved in the struggle for universal public education early on. In the midst of all of the changes and challenges, she had been attempting to find and recruit well-trained teachers, “urging alumnae of the established colleges” to take the qualifying exams and apply for teaching jobs in the New York City school system. One of the young women who had heeded Wald’s call became a Henry Street resident and a teacher at Public School No. 1 (the Henry Street School). While working, she got to know Elizabeth Farrell, who had come to teach at her school in 1899.

Elizabeth Farrell was born in 1870 and raised in Utica, New York. Her parents, like Wald’s father, were immigrants. She attended the Utica Catholic Academy and then studied teaching at the Oswego Normal and Training School (today’s SUNY Oswego), where she graduated in 1895. In 1898, after completing two more years of training, Farrell accepted a position as a teacher in a one-room school near her girlhood home, in the tiny community of Oneida Castle (then pop. 291). Soon after, Farrell moved to New York City and took up teaching at the Henry Street School (PS #1).

The school’s principal, William L. Ettinger, had put Farrell in charge of a group of children whom he described as “misfits.” They were students “unable to keep up with” their grade at school and now, because of compulsory education laws, public schools were forced to keep them in the system. Farrell could have been a glorified baby-sitter, but she took her job seriously. She had come to believe that educating special needs children to their highest level was her mission in life. Researching and experimenting with all that she learned, Farrell started to develop methods that were beginning to attract attention.

Henry Street Settlement’s resident teacher brought Wald “the glad tidings that there was a young teacher in her school [Farrell] who had ‘an idea’” about how to teach these “‘poor things.’” Wald’s confidante “submitted” that the teacher in question “‘needed looking after’”—“as if,” Wald wryly commented, “having ‘an idea’ laid her open to study, if not suspicion.” Wald immediately set about finding out more about Farrell and her work.

The first class of “misfits”** whom Farrell taught consisted of nineteen students, ranging in age from eight to sixteen years. She later described her class as “‘[m]ade up of the odds and ends of a large school,’” with “‘over-age children, so-called naughty children, and the dull and stupid children.’”** Twelve had been diagnosed “retarded.”** These children, “‘taken from any and every school grade,’” had at least one thing in common—they “‘were the children who could not get along in school.’”

Farrell’s students were often truant, and some refused to follow the school rules. Many were behind in their grade’s class work, and some could not read, write or count. Others had physical ailments that prevented them from achieving at their grade level. While some, it was true, “‘had been in trouble with the police,” Farrell believed that “they could not be characterized as criminal.’”

Farrell thought that the misbehavior of her charges and their difficulties in school was environmental as well as innate—something “‘which grew out of the conditions in a neighborhood furnished in many serious problems in truancy and discipline.’” Her analysis went against prevailing wisdom. The overwhelming consensus by the late nineteenth century was that mental illness and disability were not environmentally caused but genetic—the result of “bad blood.”** Because most doctors and scientists believed that these traits were inherited, many professionals in the field and some in government even went so far as to recommend sterilizing the mentally disabled in order to prevent them from having children. Most people also associated those who suffered from these disabilities with the criminal class. Institutionalization was recommended in order to protect society from these people.

Like Wald, Elizabeth Farrell did not believe that these children were criminals. They were also against putting children into institutions unless it was absolutely necessary. Luckily, they had cool hard fiscal facts on their side. Although many developmentally disabled people were institutionalized, the state facilities were crowded and it was wildly impractical to incarcerate everyone who had special needs. In addition, most of Farrell’s contemporaries realized that not all people with disabilities could or should be in institutions. They began to argue that the more mildly disabled could be educated, trained to work, and in the best cases might be able to live independently.

Educators and mental health professionals knew that some countries in Europe had been developing ways of educating developmentally and learning disabled children outside of institutions for years. Germany had begun to meet the challenge as early as 1859, by giving these children special instruction within the school system. By 1905, German officials estimated that 15,000 German students were receiving this type of instruction.

Lydia Chace reported in 1904 on the history of the establishment of special day classes for the mentally disabled. She noted that “In Europe, Germany was the pioneer in 1867. Norway followed her lead in 1874, and England, Switzerland and Austria in 1892.” In Prussia, Chace noted, towns having a population of at least 20,000 had been obliged to establish these types of classes and schools.

The United States began to follow the lead of Europe by the end of the nineteenth century. Providence, R.I. was the first city in the U.S. to offer a special class to the mentally disabled, in December 1896. A second class followed in December 1897, and a third was opened in Dec. 1898. Boston offered its first class starting in January 1899, and was up to seven classes by the time Chace submitted her report. Philadelphia’s Board of Education took over the work of educating the mentally disabled, which had been started by others in 1899, in the summer of 1901. By 1904, it too had grown to six or seven classes.*

Farrell began to develop her own curriculum at Henry Street’s Public School Number 1 in 1899. At its core, her methods reflected the ideas, philosophy and techniques she had learned throughout her life. She imbibed an ethos of compassion for the less fortunate and a belief that it was her duty to serve them from her elementary and secondary school training by the Sisters of Charity—an order that devoted themselves to educating, nursing, and otherwise helping the poor.

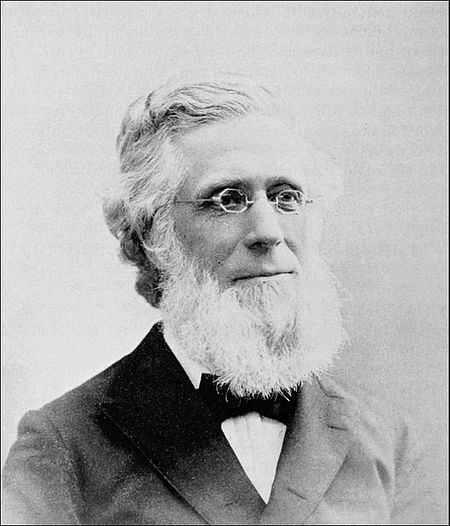

At the Oswego Normal and Training School, Farrell studied a curriculum formulated by Edward Austin Sheldon, who believed that teachers should explore and emphasize the concrete connections between school and life. He taught that education should be based upon the study of real objects, not intellectual abstractions. Sheldon, a follower of Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi, further believed that learning should be contextually based—that is, a teacher should teach something new by first placing it within the context of something familiar. His methods, embodied in the “Oswego Movement,”” were gaining popularity throughout the United States.

Farrell continued to develop her methods during her early years as a teacher. While at Oneida Castle, she taught in a tiny school district with a one-room school house. This experience honed her ability to teach students of varying levels all in the same room, in an “ungraded” class.

Elizabeth Farrell used all of the elements of her education, training and experience in that first class she taught at Public School No. 1 on Henry Street. From these—and from others she picked up in her continual search for newer and better techniques—she developed and implemented her own theory and methodology for special education. The theory relied on a combination of both the object method learning and “individualization” (seeing each child as unique and adapting to their individual learning style). She would teach students “concrete” arts or skills based upon real life experiences, but she would ground this teaching in each child’s individual talents and interests.

*There are some minor discrepancies between Chace’s dates and dates cited by other sources.

**These terms now have a derogatory and/or negative connotation, and for good reason. I have decided for the sake of historical accuracy to include them, but to use quotation marks to indicate that they were the terms used at the time, and not the terms I would choose to use today.

Bibliography

Chase, Lydia, “Public School Classes For Mentally Deficient Children,” by Lydia Gardiner Chace, Providence, RI, report compiled in Proceedings of the National Conference of Charities and Correction at the Thirty-First Annual Session Held in the City of Portland, Maine, June 15-22, 1904 scanned and online in full, Ann Arbor, MI: Univ. of Michigan Library, 2005, at http://quod.lib.umich.edu/n/ncosw/ACH8650.1904.001?view=toc

Current 3/1/17 (Chace’s report appears on pp. 390-401) (See pp. 391, 394-396).

Davis, Allen F., Spearheads for Reform: The Social Settlements and the Progressive Movement, 1890-1914, New York, Oxford University Press, 1967 (See p. 56).

Duchan, Judith Felson, A History of Speech-Language Pathology; Elizabeth E. Farrell, 1870-1932, Last revised: 04/20/2011 17:22:15 at http://www.acsu.buffalo.edu/~duchan/new_history/hist19c/subpages/farrell.html.

Duffus, R.L., Lillian Wald: Neighbor and Crusader, New York: The Macmillan Company, 1939.

The Encyclopedia of New York City, Second Edition, edited by Kenneth T. Jackson, New Haven & London, Yale University Press, 2010. “Public schools” entry, p. 1056.

[Epstein], Beryl Williams, Lillian Wald: Angel of Henry Street, [author’s name on title page is “Beryl Williams”], NY: Julian Messner, Inc., 1948.

Farrell, Elizabeth E., Inspector of Ungraded Classes, New York, Nov. 1, 1909, “Atypical Children: About 7,000 of Them Here Need Ungraded School Work.” Letter to the editor by Elizabeth Farrell, New York Times, Nov. 5, 1909 (letter dated Nov. 1, 1909).

Hendrick, Irving G. and Donald L. MacMillan, “Selecting Children For Special Education in New York City: William Maxwell, Elizabeth Farrell, and the Development of Ungraded Classes, 1900-1920,” Journal of Special Education, v. 22, no. 4, Winter, 1989 [c2001], pp. 395-417. (See pp. 396-398).

Kode, Kimberly, Elizabeth Farrell and the History of Special Education, Arlington, VA: Council for Exceptional Children, 2002 (ERIC Document ED474364) (See pp. 7-8, 14-16, 24-25, 94-95).

Mooney, “WILLIAM H. MAXWELL AND THE PUBLIC SCHOOLS OF NEW YORK CITY” (January 1, 1981). ETD Collection for Fordham University. Paper AAI8119781. In BiosGeneral.

Mooney, John Vincent, “William H. Maxwell and the Public Schools of New York City,” (1981). Etd Collection For Fordham University. Aai8119781.

Http://Fordham.Bepress.Com/Dissertations/Aai8119781 Current 3/1/17.

“Problem of Backward Children. How Science Takes Care Of Deficient Youngsters.” New York Times, November 14, 1909.

Wald, Lillian D., The House on Henry Street, NY: Henry Holt & Co., 1915. (See p. 117).

Wald, Lillian D., Windows on Henry Street, Boston: Little Brown, and Company, 1934. (See pp. 133-34).

Woods, Robert A. and Albert J. Kennedy, The Settlement Horizon: A National Estimate, New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 1922.

Illustrations

Farrell, Elizabeth, Photo/Portrait (copyright?) http://cecblog.typepad.com/.a/6a00d83452098b69e20167666511de970b-pi Current 3/6/17

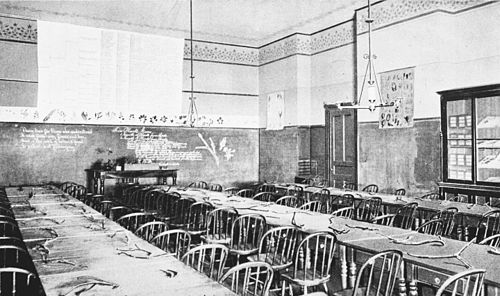

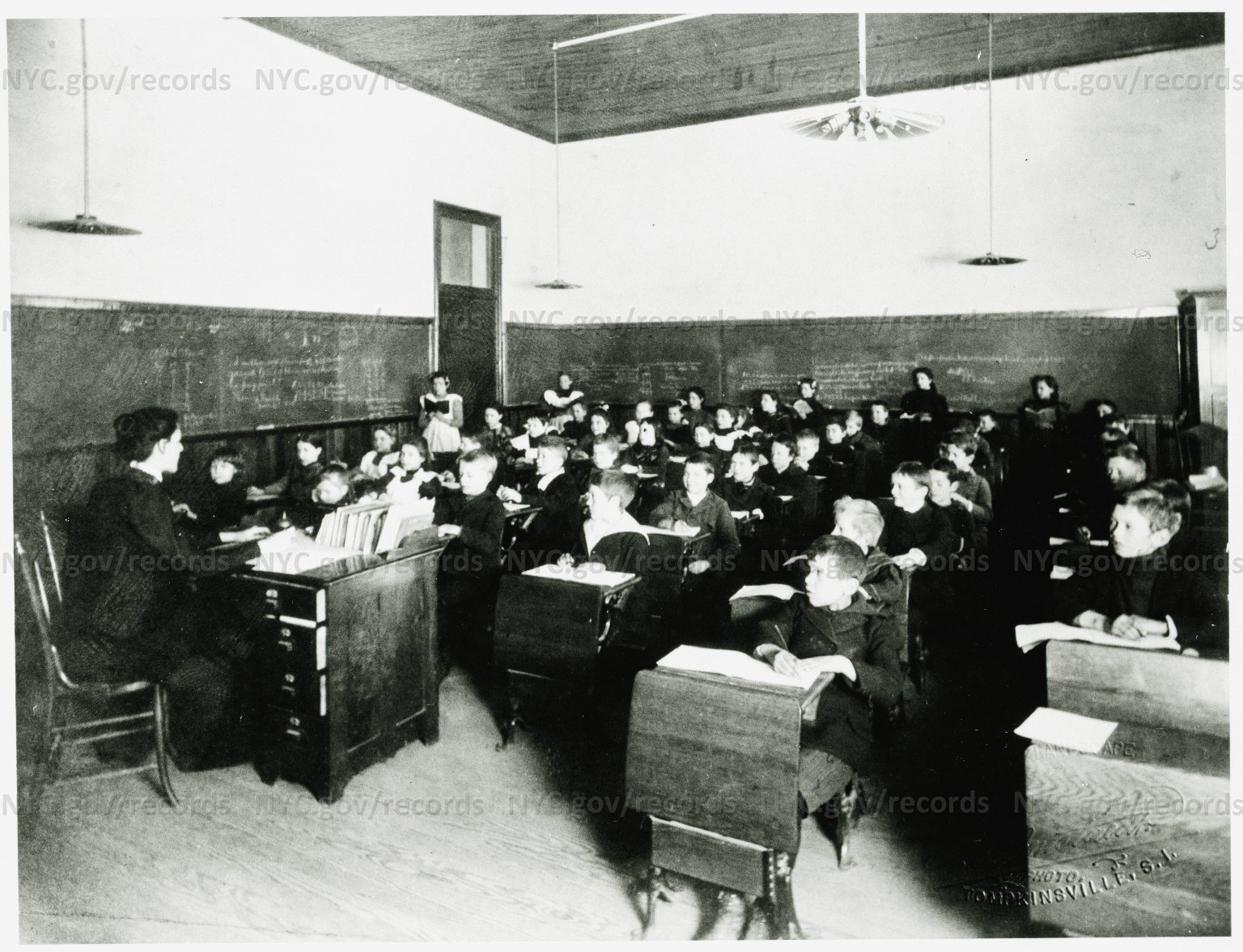

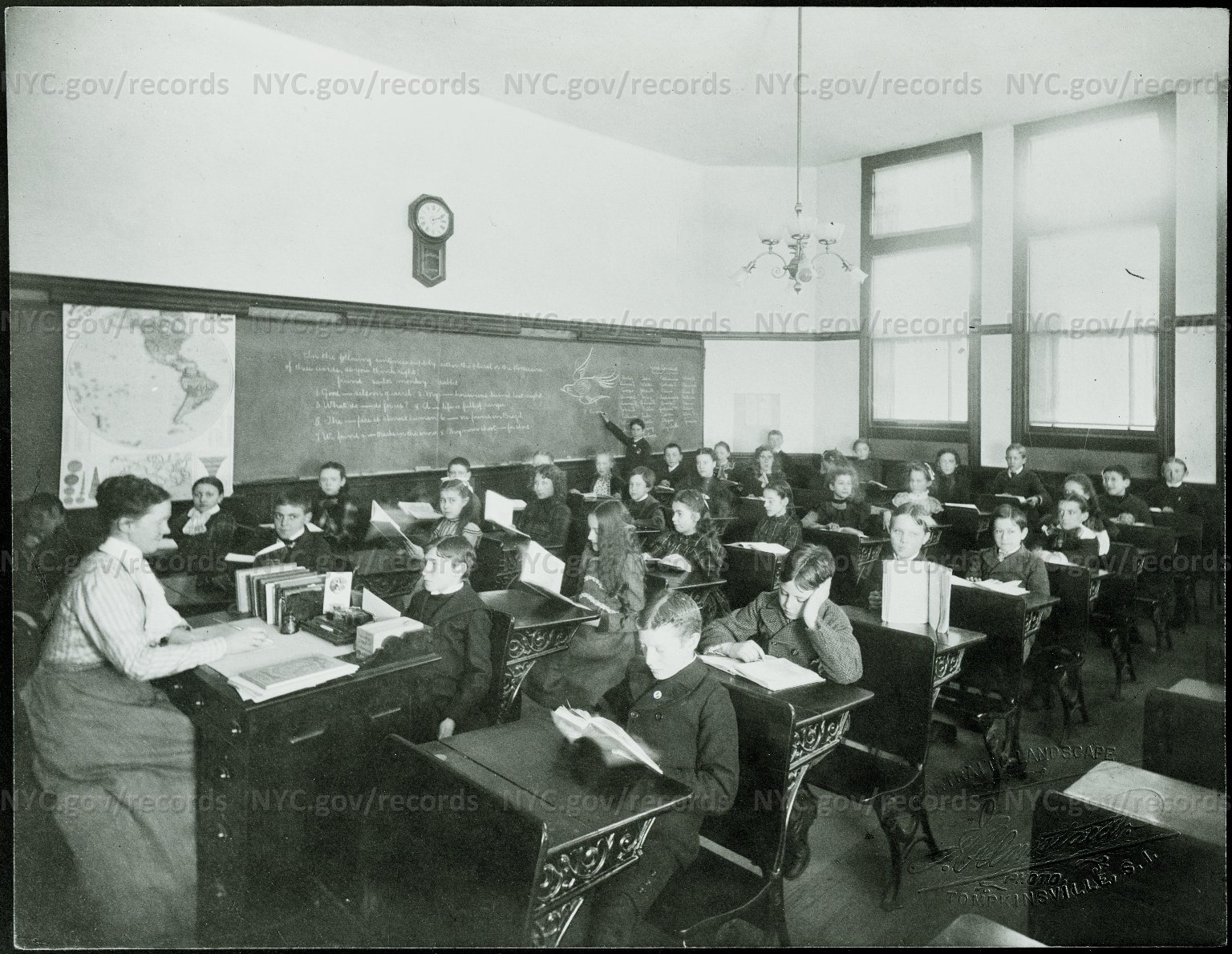

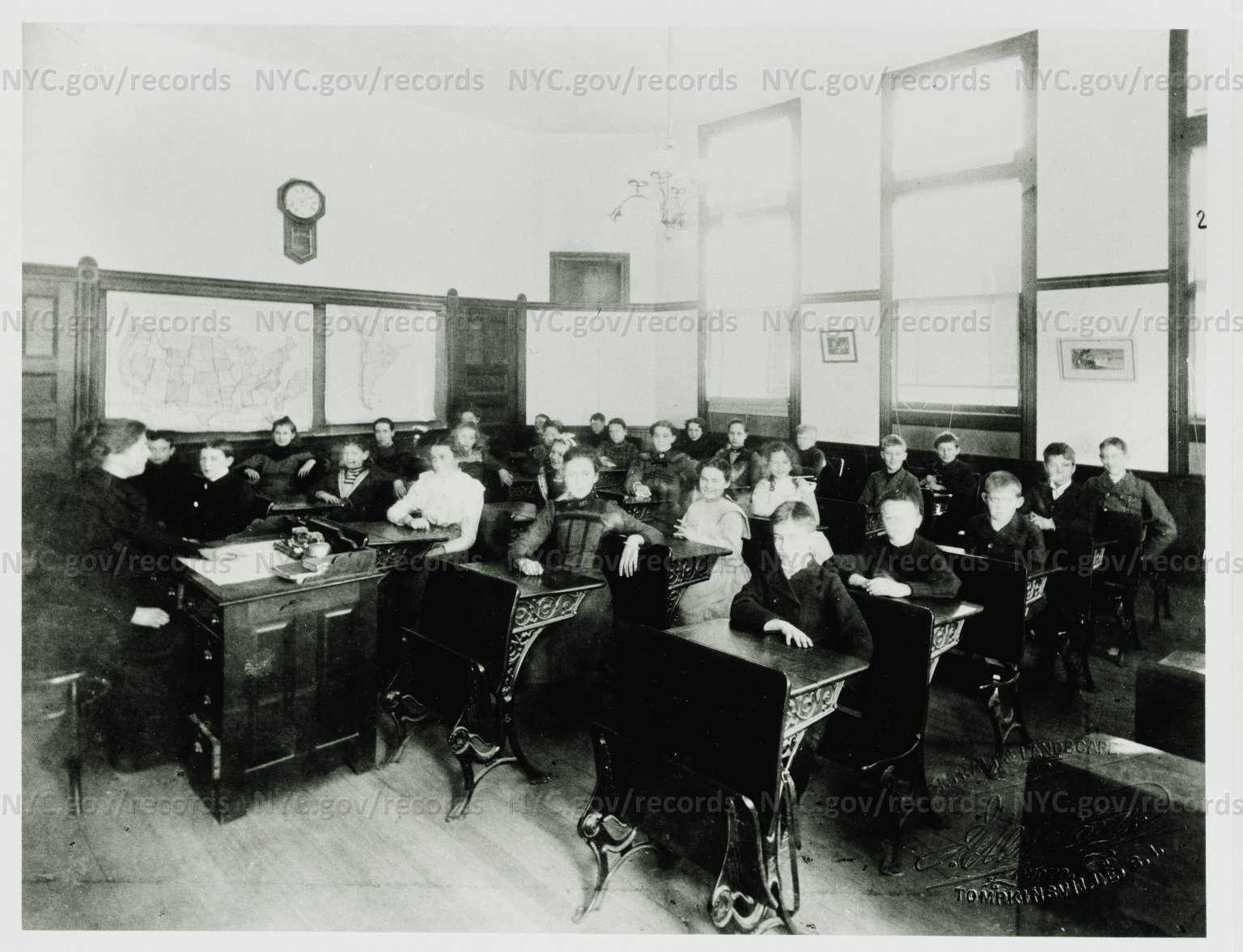

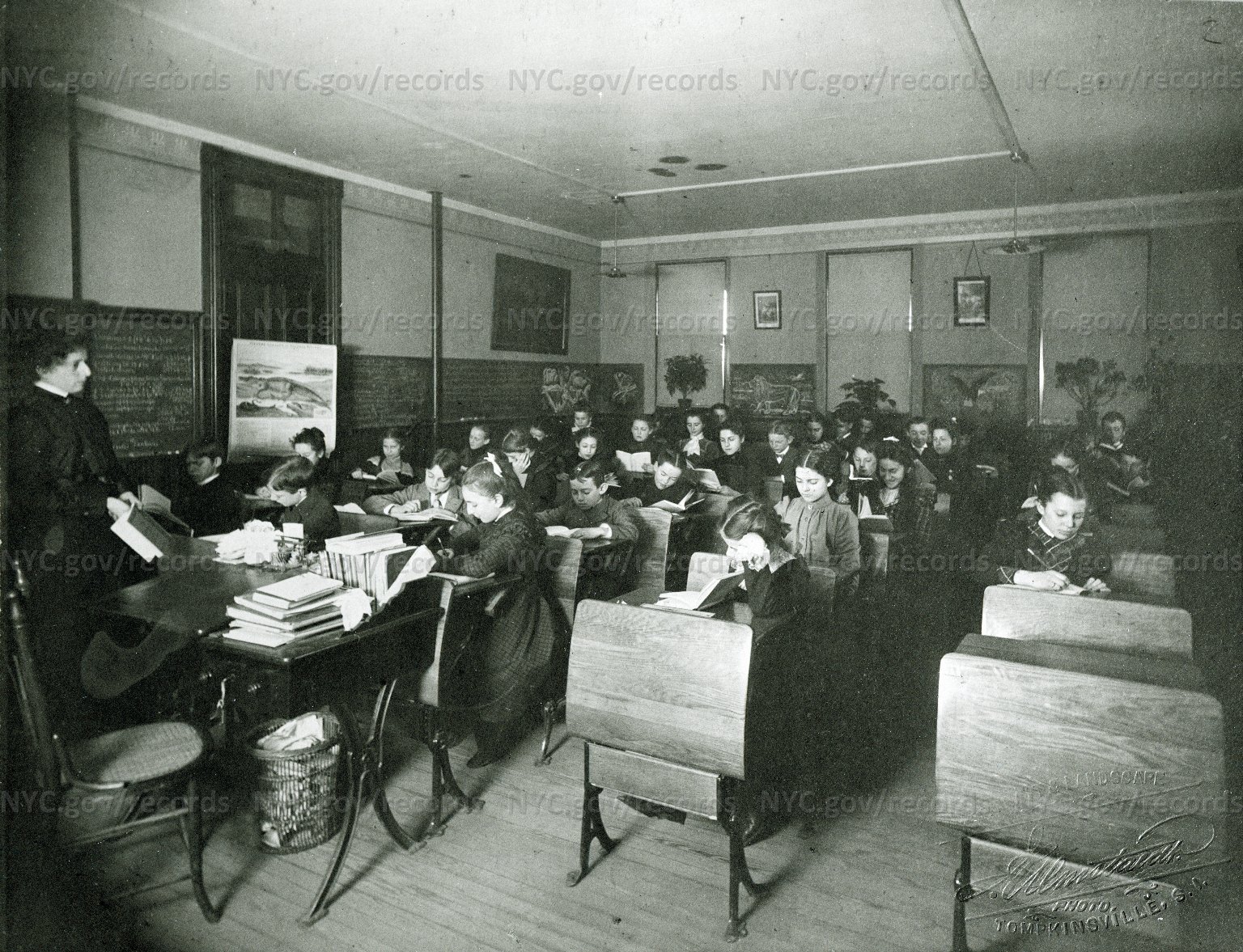

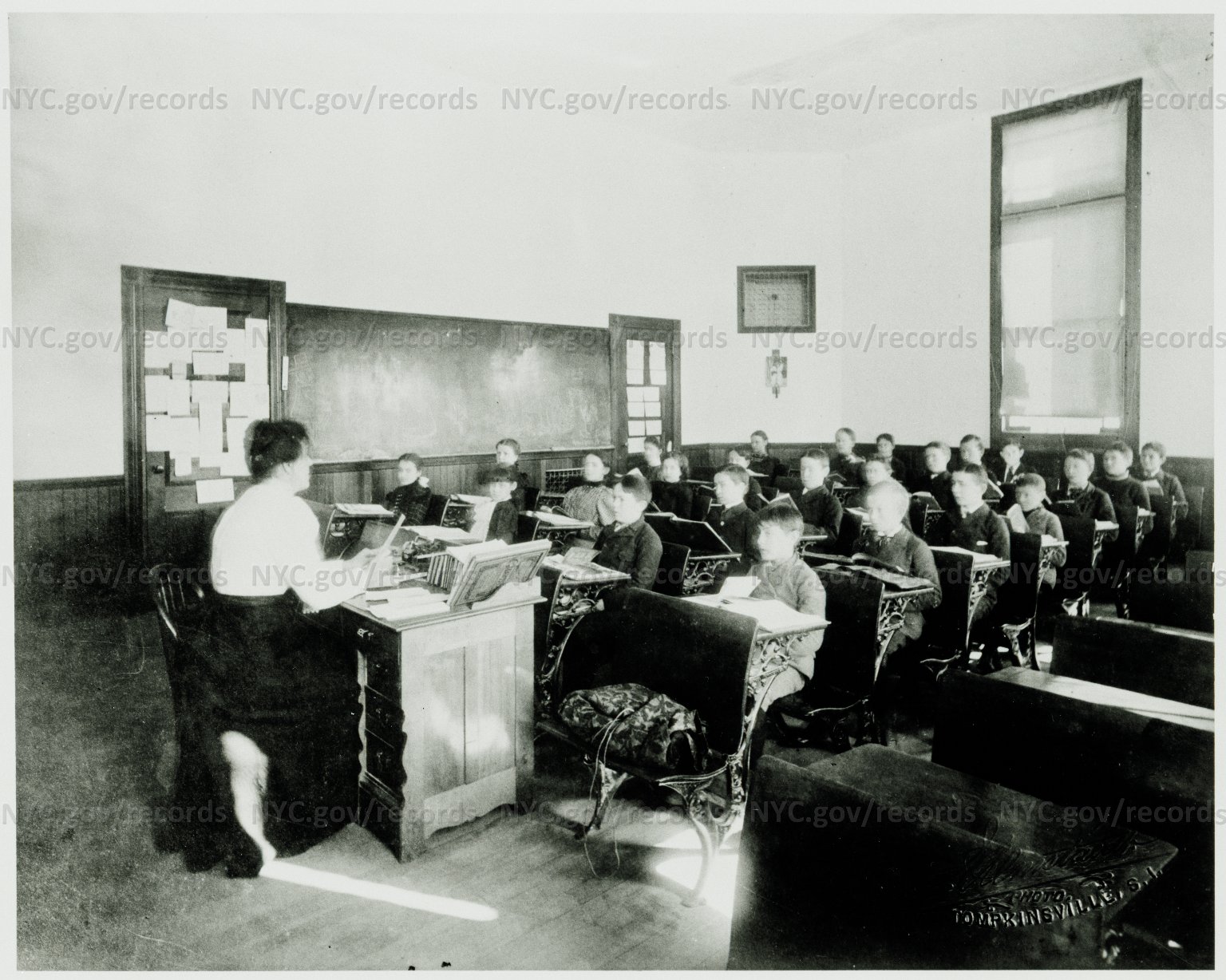

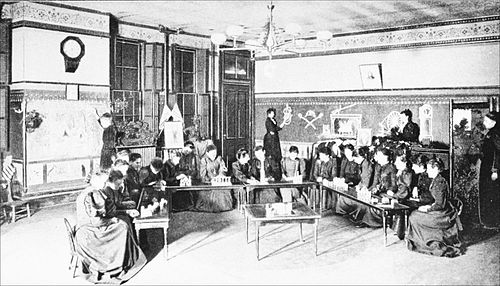

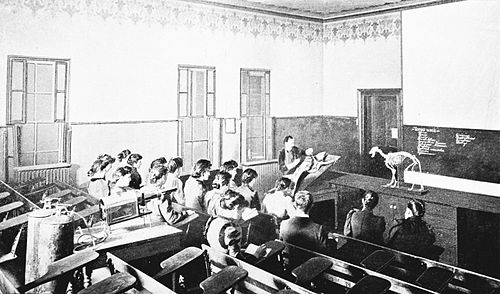

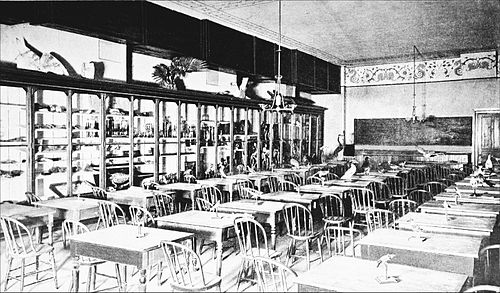

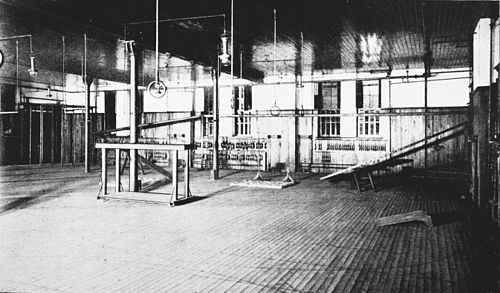

NYC DORIS, Board of Education, P.S. 17, Staten Island: classroom, 1900 (school id is tentative) Link to Illustration Current 3/6/17

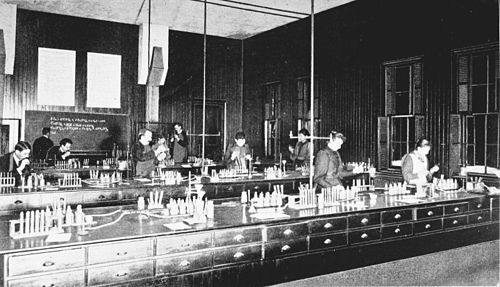

NYC DORIS, Board of Education, P.S. 16, Staten Island: classroom, 1900 (school id is tentative) NYC DORIS, Board of Education, P.S. 16, Staten Island: classroom, 1900 (school id is tentative) Link to Illustration Current 3/6/17

NYC DORIS, Board of Education, P.S. 20, Staten Island: classroom, 1900 (school id is tentative) Link to Illustration Current 3/6/17

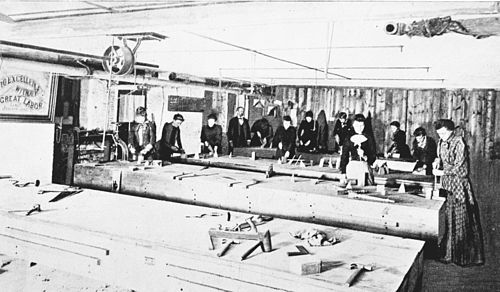

Schoolboys in a toy-making class at P.S. 1, 1900. Courtesy of New York State Archives. https://nyhistorywalks.files.wordpress.com/2012/01/sbool-boys-p-s-1.jpg Current 3/6/17

Schoolgirls in a nursing class at P.S. 1, 1900. Courtesy of New York State Archives. https://nyhistorywalks.files.wordpress.com/2012/01/school-girls-p-s-1.jpg Current 3/6/17

NYC DORIS, PS 1, Manhattan: exterior. Henry Street, Oliver Street, and Catherine Street, ca. 1900. Link to Illustration Current 3/6/17

Popular Science Monthly/Volume 43/May 1893/Oswego Normal School, entire article found at Link to Illustration Contains links to pictures that are in public domain as follows:

Edward Austin Sheldon, created 31 Dec. 1892 Link to Illustration Current 3/6/17

Old Normal School Building, created 31 Dec. 1892 Link to Illustration Current 3/6/17

Oswego State Normal School SUNY, created 31 Ded. 1892 Link to Illustration Current 3/6/17

Copyright Anne M. Filiaci 2017