By Anne M. Filiaci, Ph.D.

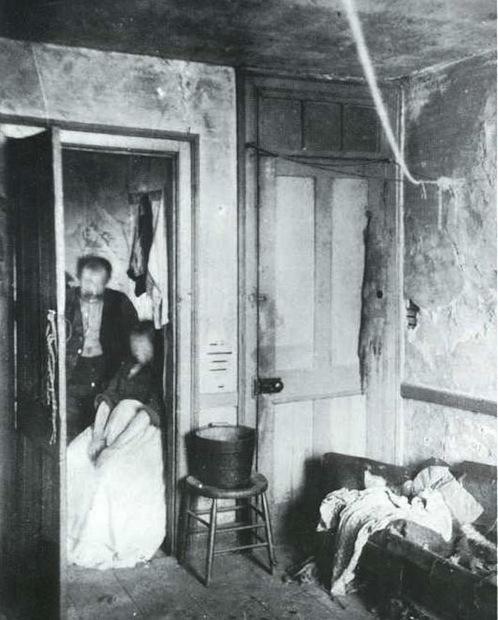

By the 1890s, reformers had worked diligently for decades, but their reports, lectures, photographs and Commissions seemed to do little good. Most of New York City’s poor lived in substandard housing, and the situation continued to deteriorate. By 1893-94, the housing problem was exacerbated by the fact that the City had become “the most densely crowded city…that the world had ever seen.” Up to four-fifths of New York’s inhabitants lived in about 38,000 tenements, and about “one-half of these live in buildings the doors of which are never closed.” Of the 38,000, at least 3,000 buildings were substandard, and

[m]any of the worst buildings, from the sanitary point of view, are in that most crowded section of the city near Essex and Mulberry Streets. There are 357,888 persons in a square mile in this neighborhood, which is 182,000 more than in London’s most densely-crowded quarter.

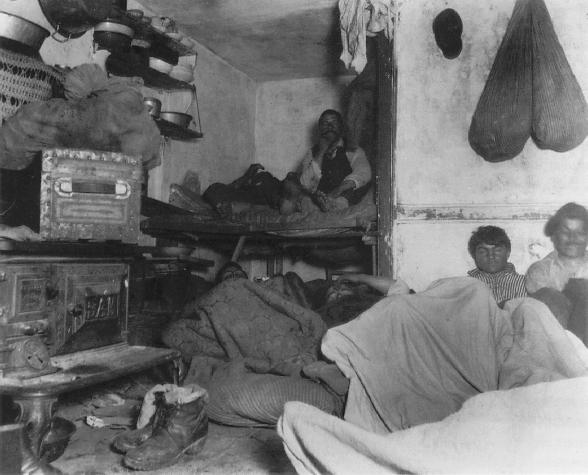

Residents of these overcrowded tenements reached their tiny rooms by climbing flights of rickety stairs through dark windowless halls. The rooms themselves depended “for their light and air entirely upon long, narrow, dark airshafts, which instead of giving light and air,” were “merely stagnant wells emitting foul odor and disease.”

The crowded and dingy quarters were made worse by an inadequate water supply to apartments—“practically none” of the “families” had “an opportunity to bathe,” which not only lowered “the whole tone of the community,” but kept them “continually sick,” crowding “hospitals and dispensaries.” The lack of sanitary conditions, the overcrowding and the dearth of clean air made tenements breeding grounds for everything from common minor illnesses to contagious and deadly diseases like tuberculosis.

The buildings were also fire hazards. Their lower floors often housed bakeries that used boiling fat in cooking, or storehouses for highly combustible hay and feed. Many stairways were made of wood, doors into apartments were not fireproof, and walls were not solid. Transoms over doors that led into hallways made apartment fires hard to contain. Where fire escapes existed, they were usually blocked by the possessions of occupants, who used them as storage spaces.

During the winter of 1893-1894, when the East Side Relief Work Committee (ESRWC) hired the unemployed to “whitewash the tenement-house cellars, alleyways, airshafts, and living rooms, they found “so much refuse” in some cellars that white washing had to be postponed in order to first clean out the “rubbish,” some of which “was thrown against the walls in piles” often reaching “three feet high.” The 3,903 barrels of trash that workers collected included “150 barrels of ashes, 100 barrels of rags, 54 of bones, 47 of leather, shoes, etc., 44 barrels of wet straw, 41 of excelsior, 29 barrels of old iron, 18 of broken glass and 18 of old tin.” They also “removed a large number of dead cats, dogs and large rate [rats] in a decomposed state,” “and large quantities of decayed garbage, including in one house several barrens of rotten sauerkraut, also putrid meat, old mattresses, filthy bedding and stale milk….” In one house, on “Fifth street,” they found “a can of milk that had been in the cellar for over a year….” That particular cellar was in such bad shape that the subcommittee refused to tackle the job. They complained to the Board of Health, which then ordered the landlord to “hire other men to do the work at his own expense….”

The ESRWC publicized conditions they found in the tenements, and in the spring of 1894, reformers succeeded in lobbying the New York State legislature to pass an act “authorizing the Governor to appoint a committee of seven to be known as ‘the Tenement-House Committee’” (1894 THC). The 1894 THC (also known as the Gilder Committee after its Chair, Richard Watson Gilder) was active for about six months.

Jacob Riis, serving as its unofficial consultant, successfully urged members to look to other cities for examples of urban planning. He also suggested that they draw up a map of New York showing ethnic neighborhoods, compile statistics on housing, and consult not only with various experts and reform advocates—trade unionists, health officials, and settlement workers—but with representatives of the poor who actually lived in the buildings as well. Riis also encouraged committee members to broaden their mandate to include recommending the creation of safe and attractive public spaces—parks, playgrounds, and other recreational areas—places that would improve the environment, health and well-being of tenement neighborhoods in general.

Shortly after it was organized, the Gilder Committee divided its tasks into five separate areas of investigation: 1) the “tenement houses” that the Health Department considered “the most unfitted for human habitation; 2) cellars that the Board of Health had “ordered vacated…as places for living and sleeping”; 3) tenements designated by the Board of Health as “overcrowded”; 4) the impact of “model tenements;” and finally 5) tenements as hazards for fire and other disasters.

The Gilder Committee produced its final report within a matter of months. Six hundred pages in length, the study enumerated the city’s housing problems and recommended, among other things,

the condemnation and destruction of unsanitary buildings, the improved construction of tenements, the securing of greater protection against the devastating effects of fire, the prevention of overcrowding, the strict enforcement of a law which forbids the covering by a tenement house of more than 70 per cent. of the lot on which it stands, increased sanitary inspection, the compulsory registration of tenement-house landlords, the speedy introduction of small parks, school playgrounds, and kindergartens; municipal baths, lavatories, and drinking fountains, electric lights and asphalt pavements, and an adequate system of rapid transit.

The THC also wrote legislation that would implement its recommendations and submitted it to the New York Legislature. Its main bill provided for

an increase in the sanitary force, for safeguards against fires in existing tenements, and for improved construction in point of light, ventilation, and safety from fire and smoke in future tenements.

Separate legislation called for the creation of small parks and open spaces in crowded tenement districts.

On January 30, 1895, the Social Reform Club held a public mass meeting in Cooper Union to discuss the Gilder Commission’s findings and recommendations. The packed audience and most of the speakers “showed a hearty approval of the reforms advocated by the Tenement House Commission” and urged passage of the Gilder Committee bills. However, attendees also made clear that they did not believe the Committee went far enough—the recommendations were, as speaker Ernest H. Crosby said, “only the first step in a long chain of steps.” Even Gilder, the Chair of the Commission, said that “more should be done…rather than less.” While they “heartily endorse[d] the report’s recommendations,” the audience expressed regret “that the committee should not have dealt with certain of the larger aspects of the problem.”

The small bore approach seemed effective. By March 25, 1895, one of the Committee’s minor legislative proposals had already been adopted. This bill asked the city to enforce existing law by completing “the construction of the three small parks created by the act of 1887”—the Mulberry Bend Park, St. John’s Park, and the East River Extension Park.”

Less than two months later, on May 21, 1895, “Richard Watson Gilder, Chairman of the Tenement House Committee, announced in a public statement…that all of the recommendations of the committee…presented to the Legislature on Jan. 17,” had finally “become laws, the last of the bills having been signed by Gov. Morton on May 9, one year from the time the committee was appointed.”

Jacob Riis enthusiastically touted the accomplishments of the Gilder Commission, proclaiming that “[g]reater work was never done for New York than by that faithful body of men.” However Riis, like the Social Reform Club, also viewed the Commission’s work as the beginning, not the end, of housing reform. “The measure of it is not to be found in what was actually accomplished, though the volume of that was great,” he wrote, but rather in “what it made possible. Upon the foundations they laid down,” he proclaimed,

we may build for all time and be the better for it. Light and air acquired a legal claim, and when the sun shines into the slum, the slum is doomed. The worst tenements were destroyed, parks were opened, schools built, playgrounds made. The children’s rights were won back for them. The slum denied them even the chance to live, for it was shown that the worst rear tenements murdered the babies at the rate of one in five. The Commission made it clear that the legislation that was needed was ‘the kind that would root out every old ramshackle disease-breeding tenement in the city.

Bibliography

“Appeal From East Side Relief Work. Over 1,200 Families Already Given Aid by Useful Employment.” New York Times, Feb. 25, 1894

Carson, Mina, Settlement Folk: Social Thought and the American Settlement Movement, 1885-1930, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1990

“Earnest Efforts to Aid the Poor. East Side Relief Work Committee’s Appeal—What Col. Murphy is Doing.” New York Times, Feb. 5, 1894

“For Better Tenements: Work of the Special Commission Meets With Approval. Mass Meeting at Cooper Union. Trinity Corporation Criticised—Addresses by Ernest H. Crosby, Richard Watson Gilder, and Others. New York Times, January 31, 1895

Friess, Horace L., Felix Adler and Ethical Culture: Memories and Studies, edited by Fannia Weingartner, NY: Columbia University Press, 1981

“Helping the Crowded Poor: Work and Aims of the Committee Investigating Tenement Houses,” New York Times, June 10, 1894

“It May Save Lives: Probable Passage of the Tenement House Bill Now in the Legislature; ONLY HALL TRANSOMS ARE FORBIDDEN; Opposition Now Only Directed Against Provisions as to Open Areas and Solid Walls—Sanitary Precautions.” New York Times, March 25, 1895

Lane, James B., Jacob A. Riis and The American City, Port Washington, NY: Kennikat Press, 1974

Lubove, Roy, The Progressives and the Slums: Tenement House Reform in New York City, 1890-1917, np: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1962

“Reform in Tenements: Health and Morals of Their Inmates Improved,” New York Times, November 28, 1896

“Reinhard Committee Meets: R.W. Gilder Says ‘Sweat Shops’ Are a Crying Evil. Excellent Advice From Secretary C.E. Marshal—Views of J.B. Reynolds and Mrs. Gilbert Robinson,” New York Times, Oct. 27, 1895

Report of the Tenement House Committee as Authorized by Chapter 479 of the Laws of 1894. Transmitted to the Legislature January 17, 1895. Albany: James B. Lyon, State Printer, 1895. Full text by Google Books at https://archive.org/details/reporttenementh00commgoog Current 11/13/15

Riis, Jacob, The Children of the Poor, New York, Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1908 (c1892) http://archive.org/stream/childrenofpoor00riisuoft#page/20/mode/2up (openlibrary.org) Current 11/23/15

Riis, Jacob, How the Other Half Lives: Studies Among the Tenements of New York, New York, Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1890. Several fulltext copies online, including https://archive.org/stream/howotherhalfliv00riisgoog#page/n8/mode/2up , current 11/23/15

Riis, Jacob A., The Making of an American, [no place] BiblioBazaar, 2002 (originally published 1901)

Simkhovitch, Mary Kingsbury, Neighborhood: My Story of Greenwich House, NY: W. W. Norton & Co., Inc., 1938

“Tenement House Reform: R.W. Gilder Outlines the New State Legislation; More Power for City Departments; All of the Committee’s Recommendations Embodied in Laws—Greater Protection to Health and Life,” New York Times, May 22, 1895

“Tenement House Reform: Radical Changes Suggested By a Committee of the Charity Organization Society, New York Times, July 9, 1899

Trachtenberg, Leo, “Philanthropy That Worked,” from City Journal, (Winter 1998) at http://www.city-journal.org/html/8_1_urbanities-philanthropy.html Current 10/22/15

Wald, Lillian D., The House on Henry Street, N:Y: Henry Holt & Co., 1915

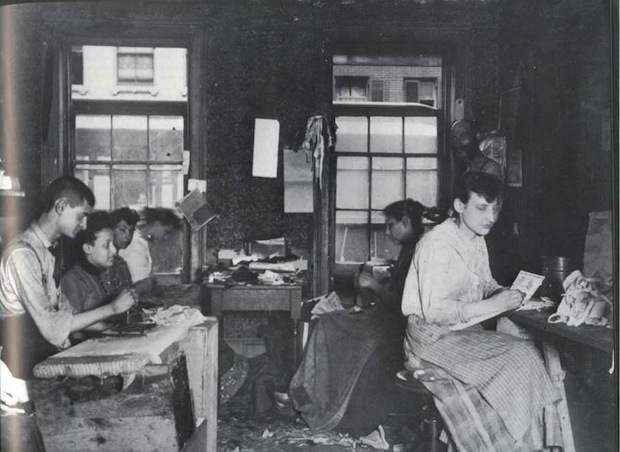

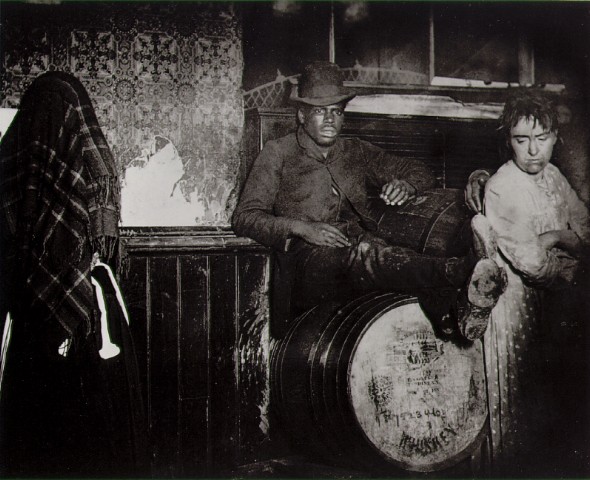

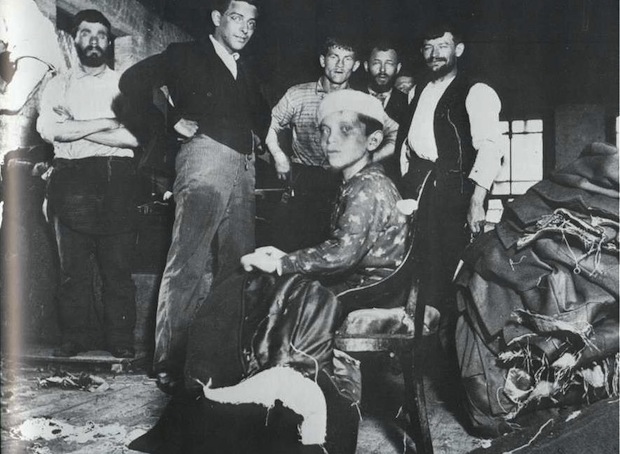

Illustrations

Various scenes, 62 images of New York City streets, tenements, etc. Most are by Riis and appear in his books Link to Illustrations Current 3/28/21

Library of Congress, Mulberry Street, New York City, Digital ID: (digital file from intermediary roll film) det 4a31829 Link to Illustration, Reproduction Number: LC-USZC4-1584 (color film copy transparency) LC-USZC4-4637 (color film copy transparency) LC-USZCN4-45 (color film copy neg.), Repository: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA (ca. 1900) Link to Illustration Current 3/28/21

LOC, Title: [Jewish market on the East Side, New York, N.Y.] Related Names: Detroit Publishing Co. , publisher. Date Created/Published: [between 1890 and 1901]

Medium: 1 negative : glass ; 8 x 10 in. Reproduction Number: LC-D401-12426 (b&w film copy neg.) LC-DIG-det-4a07950 (digital file from original) Rights Advisory: No known restrictions on publication. Call Number: LC-D4-12426 <p&p> [P&P]

Repository: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA Notes: Title and date from Detroit, Catalogue J (1901). “Dup” on negative. Detroit Publishing Co. no. 012426. Gift; State Historical Society of Colorado; 1949. Link to Illustration Current 11/23/15</p&p>

NYC Dept. of Records Link to Illustration Current 3/28/21

Collection: DEG: DeGregario Collection

Identifier: deg_35

Title: Street scene: tenements, store, barrels

Creator: Robert J. Delvin

Subject: Street Scenes

Description: Probably Essex Street, between Grand and Hester Streets: A. Feinberg, Wallpaper at #36

Date: 1880-1899

Type: Image

Format: Lantern Slide

Format: 3 1/4 by 4 inches

Source: Private donation from Mr. & Mrs. Felice DeGregario

Coverage: New York

Notes: Lantern slide collection probably originated with the New York Camera Club. All listed photographers were members.

Riis, Jacob, The Children of the Poor, New York, Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1908 (c1892) Link to Illustration (openlibrary.org) Current 3/28/21

Riis, Jacob, How the Other Half Lives: Studies Among the Tenements of New York, New York, Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1890. Several fulltext copies online, including Link to Illustration, current 3/28/21

Digitization of photos in Riis, Jacob, How the Other Half Lives: Studies Among the Tenements of New York at PetaPixel. (“Established in May of 2009, PetaPixel is a leading blog covering the wonderful world of photography. Our goal is to inform, educate, and inspire in all things photography-related.” Link to Illustration current 3/28/21

Also see results from Google Images search, “how the other half lives,” Link to Illustration current 3/28/21

“Jacob A. Riis’s New York,” slide show by New York Times, at Link to Illustration current 3/28/21

Copyright Anne M. Filiaci 2016