By Anne M. Filiaci, Ph.D.

Soon after Lillian Wald moved to the Lower East Side, she met Josephine Shaw Lowell, who became one of her earliest friends and mentors. Shaw Lowell had been involved in New York City philanthropy since the early 1870s. By the 1890s she had become one of the City’s most influential and effective activists.

Josephine Shaw Lowell was born on December 16, 1843 in West Roxbury, Massachusetts, a town about nine miles from Boston. Her parents, Francis and Sarah Shaw, were wealthy members of New England society. As radical abolitionists, they counted many of the period’s prominent reformers among their friends. Their neighbors included the residents of Brook Farm, a utopian community inspired by and modeled on transcendentalist philosophy.

In 1847, the Shaw family moved to Staten Island, New York. Four years later they embarked on an extended trip to Europe, where they remained for almost five years. While in Europe, Josephine became proficient in German, French, and Italian. For several months during her final year there, she studied at a Catholic girls’ school in Paris. After returning to Staten Island in 1855, Josephine attended Miss Gibson’s school. She went to Boston for the final two years of her formal education, finishing there at the age of eighteen.

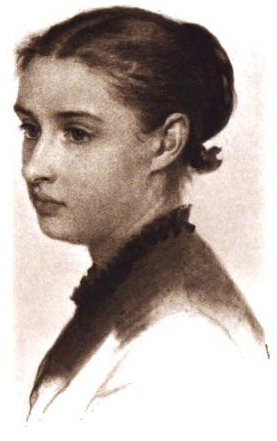

Josephine Shaw grew into a delicate, ethereal-looking young woman of medium height, with brown eyes and auburn hair. Her friends and acquaintances described her as gracious and sympathetic, possessed of a clear intellect, a wonderful sense of humor, and an impressive ability to get things done.

An ardent supporter of the North in the American Civil War, Shaw remained true to the Union’s ideals even as the War’s ravages became the cause of great personal loss. First, in early 1863, she and her family were devastated when her brother, Robert Gould Shaw, lost his life fighting against the Confederacy. That same year, on October 31st, Josephine found a respite, from her sorrow when she married Colonel Charles Russell Lowell, Jr. after a brief courtship. The couple spent a quiet winter living at his headquarters in Vienna, Virginia, where the new bride devoted herself to caring for sick and wounded soldiers in nearby military hospitals. But the marriage was cut short when Charles Russell Lowell also died in battle on October 20, 1864, less than a year after the wedding.

A month and a half later, on November 30th, Josephine gave birth to their daughter, Carlotta Russell. The young widow never remarried. She dressed in black mourning clothes for the rest of her life, which she spent raising her daughter and devoting herself to charitable causes.

Even before she married, Shaw (Lowell) had worked as a volunteer for the Women’s Central Association of Relief (WCAR), an organization founded by physician Elizabeth Blackwell in 1861 to coordinate the charitable efforts of northern women during the Civil War. After she became a widow, Shaw Lowell raised money for the National Freedmen’s Relief Association of New York (NFRANY), an organization founded in 1862 to help African Americans who lived on land that was occupied by the northern army. She traveled to Virginia in 1866 on behalf of NFRANY in order to inspect and report on the condition of African American schools in that state.

In the early 1870s, Shaw Lowell worked with the New York State Charities Aid Association, a group that visited, inspected, and reported upon conditions in New York’s jails and almshouses. In 1875, she led a statewide study of able-bodied paupers. In the spring of 1876, New York Governor Samuel J. Tilden appointed her to be the first woman Commissioner of the New York State Board of Charities. As a member of the Board, Shaw Lowell investigated and reported on conditions in poorhouses, jails, hospitals, mental institutions (then called asylums) and orphanages throughout the state.

Shaw Lowell’s work led her to believe that those in need of charity should not be kept en masse in workhouses, which was still the fate of many of the impoverished at that time. The able-bodied poor, she thought, should be released and provided with work, while orphaned children should, as much as was possible, be placed in private homes. The rest of the workhouse population, she argued, should be segregated into separate institutional settings that would explicitly address their needs—institutions for the mentally ill, group homes for delinquent girls, etc. She spent years working and lobbying state and local legislatures to bring about these changes in addressing the needs of the poor.

Copyright Anne M. Filiaci 2016