NEW YORK CITY PAYS FOR SCHOOL NURSES

Lina Rogers, a resident of the Henry Street Settlement, was the first school nurse to be “placed on the [New York] city payroll” in the fall of 1902. Rogers related the series of events leading up to her appointment when she spoke at the annual convention of the Nurses’ Associated Alumnae in May of 1908. “After a month’s experimental work,” she recalled, “…the results were considered so satisfactory that twelve nurses were appointed” in “forty-eight schools (four schools for each nurse).” After another month had lapsed, the Board of Health decided that “the work had passed the experimental stage and had fully demonstrated its practical value as a supplement to its medical inspectors.”

" order_by="sortorder" order_direction="ASC" returns="included" maximum_entity_count="500"]The City, thus presented with overwhelming evidence of the value of nurses in schools, soon “modified” its policy of “ordering no treatment” for medically excluded children. Nurses were now “instructed by the orders of the Department of Health” to “give specified local treatment in all cases” where students could “safely remain in school” as long as they received “care and daily supervision.” From now on, a child who had “a case of” a minor, controllable contagious disease—for example, “ringworm”—would be able to stay in school.

The City’s Board of Estimate and Apportionment appropriated $30,000 for the following year (1903), which “provided a staff of twenty-seven nurses at a salary of nine hundred dollars each per year, under one supervising nurse,” Lina Rogers. The twenty-seven nurses served 219,239 students in 129 schools (125 public and four parochial).

School nurses continued to achieve impressive results during the first year of the new program. According to Rogers, under the old system of medical inspection “the number excluded was 10,567 for the month of September, 1902.” During the month of September, 1903, “with the nurses in the schools, only 1101 were excluded,” –roughly ten percent of the previous year’s total. For the “quarter ending December 3, 1903,” official data showed that “four hundred would be the actual number of exclusions as against 24,538 under the old system.” This represented a 98.4% drop in exclusions in the span of one year.

Once the program became permanent, health professionals devised a routine for the supervising nurse and the school nurses. According to Dr. Josephine Baker, they “established a clinic in each” participating “school, and “supplied” the clinic “with simple remedies.” Children who had been diagnosed with minor contagious diseases would now be able to report “each day to the nurse for the appropriate treatment.”

Lina Rogers, as “supervising nurse,” had “entire charge of the school nurses.” She also acted as liaison between the nurses and the school system. It was up to her to “make arrangements for beginning work in the schools and to see” that the Department of Education provided “the necessary supplies.” Hers was an oversight role, with responsibility “for the efficiency and character of the work performed by each nurse, in all boroughs of the city.” She received all “[a]pplications for the position of school nurse,” interviewed “each applicant,” investigated each applicant’s “credentials,” and then forwarded the “result of investigations,” along “with her recommendation to the Board of Health.” Once a nurse had been hired, Rogers assigned her to cover specific schools and gave her a schedule for visiting them. Rogers also regulated “the proper amount of work for each nurse,” inspected each nurse’s work, and made all necessary “changes and transfers.”

When a nurse entered “the school for the first time,” she reported “to the principal” and obtained “a place in which to work and the method for receiving the children designated by the medical inspector.” Sometimes the assigned workplace left much to be desired. Rogers recalled her first space as

the only available place that could be found, which was a corner of the indoor playground, the window-sill doing duty for a table. All the necessary dressings, etc., including the basins used, were furnished by the Nurses’ Settlement.

Next, the nurse interviewed the inspecting doctor and obtained data from his or her “cards”—name of child, disease the child had, date the child was ordered under treatment, date of exclusion, and date of readmission. The nurse copied this information onto her own “duplicate set of cards,” organized the cards by class, and sent a “monitor” to escort “a limited number of children” to her makeshift clinic while she prepared her “dressing table.” As the first set of children were being treated, monitors retrieved others who needed care, with “each child returning to classroom as soon as cared for, thus preventing delay and confusion.”

According to Darlington, nurses did not make diagnoses, and their treatment role was circumscribed. They were allowed to treat only a limited number of diseases: “pediculosis, conjunctivitis, ringworm, impetigo, favus, molluscum contagiosum and scabies.” Each nurse treated these cases “as directed,” using “definite rules” that were “given” to her “as to how to treat” the “cases sent to her for treatment.”

Course of Treatment Outlined by the Department of Health

Pediculosis. – Saturate head and hair with equal parts kerosene and sweet oil, next day wash with solution of potassium carbonate (one teaspoonful to one quart of water) followed by soap and water. To remove “nits” use hot vinegar.

Favus, Ringworm of Scalp. – Mild cases: scrub with tincture green soap, epilate, cover with flexible collodion. Severe cases: Scrub with tincture green soap, epilate, paint with tincture iodine and cover with flexible collodion.

Ringworm of Face and Body. – Wash with tincture green soap and cover with flexible collodion.

Scabies. – Scrub with tincture green soap, apply sulphur ointment.

Impetigo. – Remove crusts with tincture green soap, apply white precipitate ointment (ammon. hydrarg.).

Molluscum Contagiosum. Express contents, apply tincture iodine on cotton toothpick probe.

Conjunctivitis. – Irrigate with solution of boric acid.”

Years later, Dr. Josephine Baker would remember “the lines of little girls with their pigtails pulled forward over their eyes so that the nurses could look through their hair” for lice. This particular “method of attack,” she noted, was not without “hazards”—all the nurses who worked in the schools “periodically acquired lice themselves.” Even Baker, “who seldom had to do” the “work of inspection,” was unable to avoid “that infection on several occasions.”

In the case of “infectious skin diseases,” the nurse “applied” a “protective treatment to keep the infection from spreading.” Once this was done, the child “could stay safely in school without danger of spreading the infection to others.”

Nurses did not, however, treat trachoma, and children who had this serious contagious disease—which could result in blindness—did not remain in the classroom with uninfected children. Instead, the City established “special classes” in the schools, where infected children “could go on with their studies but were not allowed any contact with the other children in the schools.”

Each school nurse kept “a record of all cases treated by her at her schools” and provided Rogers with a “weekly written report.” Rogers reviewed, revised and corrected the weekly reports and then wrote a “general summary” that she “forwarded to the chief inspector.” Rogers also met each nurse in person at school every week.

The school nurse’s job did not end with treating children inside the school and then sending them back to the classroom. Before she left each of her schools, the nurse had to visit its clerk and picked up a copy of the “list of the names of children excluded by the medical inspector”—children who were “absent on account of illness.” She then visited each of these children in their homes. Sometimes she used these visits “to instruct parents in the proper way of caring for” children at home; other times she visited those “who did not return to school for reinspection on the day appointed by the school inspector.” Rogers characterized this “part of the work of school nurses” as “by far the most important in its direct influence.” She saw the “care given to the children in the schools” as “ameliorative,” while “that given in the homes” was “the preventive part of the whole.”

Although medical inspectors sent “exclusion cards” home with every infected child, the cards often proved useless. Many parents could not read English and/or did not understand medical terminology. Sometimes they did not even attempt to read the cards, but left them “unopened,” resting “behind clocks and on the mantel shelves.” The “nurse’s first duty” was thus “to explain why the child” had “been sent home” from school.

The nurse next told “the parents what must be done” in order to make the child well and able to return to school. She often included a “practical demonstration” on how to treat an illness while giving instructions. In cases of head lice, nurses saw themselves as engaged in “home-missionary work, teaching whole families that a shampoo and a fine-tooth comb technique followed by soaking the hair in kerosene to kill the nits would accomplish our purpose.”

If it were appropriate, the nurse suggested that the family visit a physician. If they could not afford a doctor, she gave them the location of “the proper dispensary.” In cases where mothers were too busy to seek medical help—either with work or with young children—the nurse would “make arrangements to have the children taken to the dispensary to ensure” that “treatment is being given.”

In many cases, nurses “detected” that “unsanitary conditions” caused “the very trouble the children were being excluded for.” Sometimes they were able to solve this problem by educating parents—teaching, for example, that “contagious eye trouble” would persist as long as “the whole family using the same towel and other linen” or that in the case of head lice, “it was useless to keep the school child clean if all the others in the family were neglected.”

At other times visiting school nurses found situations that could lead to serious consequences for the general welfare. When one nurse entered “a room without a window” in a child’s home, she saw what at first appeared “to be a bundle of rags on a cot,” but proved instead to be “a man in the last stages of [very contagious] tuberculosis.” In another case, a nurse found a child, sent home “with a severe form of scabies,” who was “helping to finish and carry…bundles of sweat shop clothing”—clothing that would then spread the contagious disease to unsuspecting buyers.

Nurses who visited schoolchildren in their homes often encountered environments that violated the city’s housing laws, constituting yet another threat to the general welfare. “[B]ad conditions of drains and sewers,” and “filthy conditions of yards” where “children played” hastened the spread of disease. In these cases, nurses reported conditions and “non-observances of the law” to “the proper authorities.”

Within a short time, the nurses’ work resulted in higher school attendance and in the eradication or proper management of many once-common diseases. By 1908 pediculosis, or head lice, had “almost entirely disappeared where nurses are in attendance at schools.” “Our war on pediculosis in the New York City slums,” Dr. Josephine Baker wrote, had “turned a matter-of-course condition into a disgrace.”

In 1904, the number of schools served by nurses increased by fifty-two, and the nursing staff was upped to thirty-three. In the Borough of Manhattan, the total number of treatments provided by school nurses for the year 1903 was 285,793. That number included 156,886 for pediculosis; 106,257 for contagious eye diseases; 3,379 for eczema; 8,498 for ringworm; 335 for scabies; and 10, 438 for various other ailments. This impressive number of treatments had been given by a total of less than twenty nurses, whose visits totaled 24, 282 (12,891 visits to tenement houses; 11,098 visits to schools; and 293 “miscellaneous visits.”

In 1904, twenty nurses made 19,524 visits to tenements, 16,155 visits to schools, and 607 “miscellaneous” visits. In the following year, 1905, forty-four nurses served “one hundred and eighty-one public schools,” as well as “twenty parochial schools and three industrial schools” that were “under separate management.”*+

Lillian Wald was instrumental in putting nurses into the City’s schools. As a result of her actions, a health policy that was failing became successful. General public health improved. And poor children in New York City now not only had a better chance of getting decent medical care and remaining healthy. They also had a better chance to get a formal education.

*Rogers stated that “Parochial schools are supported by the Church and industrial schools by Boards of Trustees, the Department of Education allowing fifteen dollars ($15) per capita.”

+All statistics are provided by Rogers and Darlington in the sources cited below.

Bibliography

Baker, S. Josephine, Fighting For Life, NY: The Macmillan Company, 1939.

Darlington, Thomas, “Precautions Used By The New York City Department Of Health To Prevent The Spread Of Contagious Disease In The Schools Of The City.” By Thomas Darlington, M.D., Commissioner of Health of New York City. From Medical News: A Weekly Journal Of Medical Science. Vol. 86. New York, Saturday, January 21, 1905. No. 3, Pp. 97-104. Find from Google Books at: Link

Hanink, Elizabeth, “Lina Rogers, the First School Nurse,” Working Nurse nd. Link to article with image http://www.workingnurse.com/articles/lina-rogers-the-first-school-nurse Link to image only: http://www.workingnurse.com/images/articles/big/webschool_nurse3_small.jpg

Rogers, Lina L. “Some Phases of School Nursing” by Lina L. Rogers, R.N. Supervising School Nurse, New York City. American Journal of Nursing, 1908, 8 (12), 966-974. (Re-printed with permission from the American Journal of Nursing, in Journal of School Nursing, October 2002).

Wald, Lillian D., The House on Henry Street, N:Y: Henry Holt & Co., 1915.

Illustrations

Baker, Josephine, Photos from NIH, National Library of Medicine, Changing the Face of Medicine: Josephine Baker Biography Photo Gallery, https://cfmedicine.nlm.nih.gov/gallery/photo_19_1.html Current 1/18/17 and https://cfmedicine.nlm.nih.gov/gallery/photo_19_2.html Current 1/18/17 Can also be accessed at bottom of bio, https://cfmedicine.nlm.nih.gov/physicians/biography_19.html Current 1/20/17

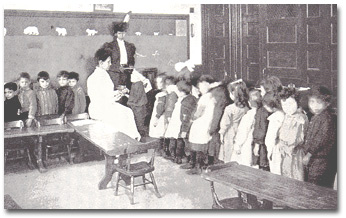

Rogers, Lina, with schoolchildren http://www.harvardsquarelibrary.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/07/jb2-baker6a.jpg Current 1/20/17

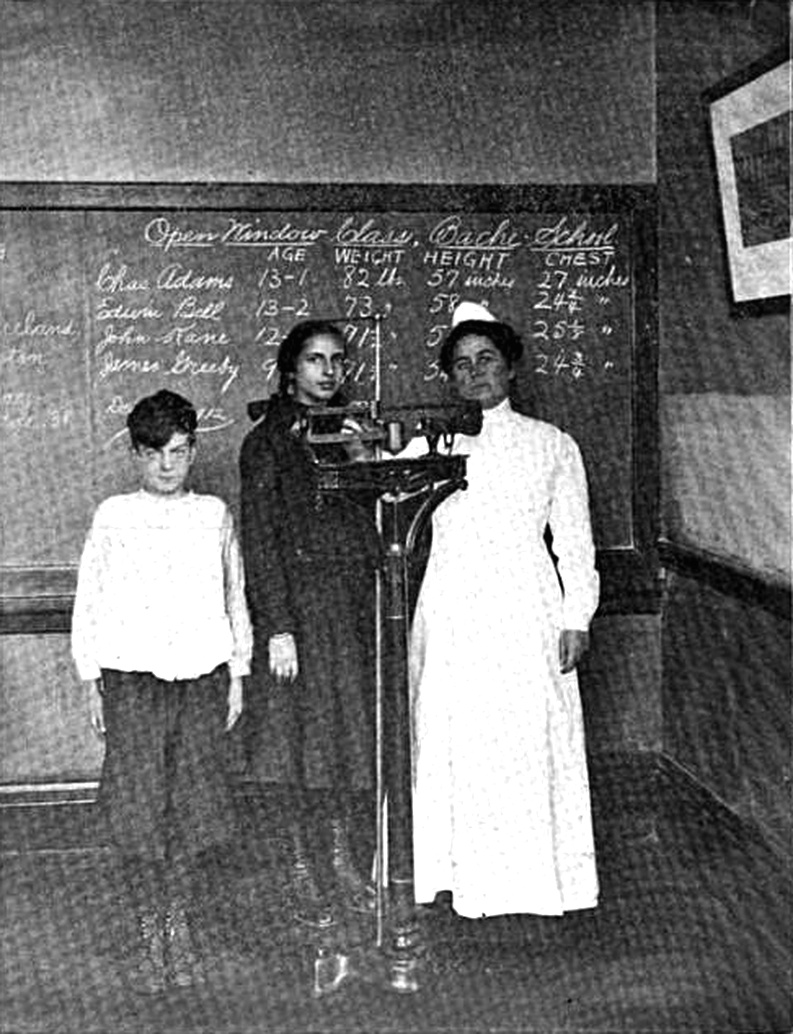

School nurse weighing and measuring pupils, Philadelphia PA ca. 1912 This IMAGE (or other media file) is in the public domain because its copyright has expired. This applies to the United States, where Works published prior to 1978 were copyright protected for a maximum of 75 years. Works published before 1923 (in this case c 1913) are now in the public domain. Title: American journal of public health: the journal of the American Public Health Association, Volume 3, Issues 1-6. Author: American Public Health Association. Publisher: American Public Health Association, 1913. Original from: the University of California. Digitized: Aug 3, 2007. Subjects: Medical › Public Health Medical / Public Health, Public health

TEXT CREDIT: American journal of public health: the journal of the American Public Health Association, Volume 3, Issues 1-6 http://publicdomainclip-art.blogspot.com/2011/09/school-nurse-weighing-and-measuring.html Current 1/20/17

French, Hilary and Brittlin Yamaguchi, Lina Rogers, slideshow, Jan. 20, 2014. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IYjteKvJIhg Current 1/24/17

Hanink, Elizabeth, “Lina Rogers, the First School Nurse,” Working Nurse nd. Link to article with image http://www.workingnurse.com/articles/lina-rogers-the-first-school-nurse Current 1/24/17 Link to image only http://www.workingnurse.com/images/articles/big/webschool_nurse3_small.jpg Current 1/24/17

Copyright Anne M. Filiaci 2016