By Anne M. Filiaci, Ph.D.

It soon became obvious that Lillian Wald possessed not only the training but the personality and work ethic to build a successful enterprise. She was fearless, compelling, and persuasive in her bid to attract wealthy donors and influential supporters. Once she got them on board, she made sure that she kept them there, maintaining frequent contact, doing favors for them when she could, and proving through both effort and implementation that their time, money and support was well spent.

" order_by="sortorder" order_direction="ASC" returns="included" maximum_entity_count="500"]From her earliest days on the Lower East Side, Lillian Wald wrote frequent reports to her principal donors, Mr. Jacob Schiff and his mother-in-law, Mrs. Solomon [Betty] Loeb. In these communications, she advised them on the details of her work and how she spent the money they gave her. She usually composed the reports at night, after an exhausting day at work. During winters at the Jefferson Street apartment, this meant that she wrote while sitting “in the kitchen of our little apartment with” her “feet in the oven, as it was too cold to hold a pen in the frigid temperature of the room….”

Wald’s thoughtfulness, hard work and diligence paid off. Schiff and Loeb, pleased with the work of the young nurses, soon successfully persuaded others to support the cause. Loeb recruited friends like Mrs. John Crosby Brown and her husband, a partner in the investment bank Brown Bros. & Co., to donate money. Meanwhile, Jacob Schiff made sure that Wald and Brewster got support from important institutions that worked in the neighborhood.

On May 9, 1893—even before the nurses moved to the Lower East Side—Schiff convinced the superintendent of the United Hebrew Charities (UHC) to make their attending physicians available to the nurses for consultation. Wald soon developed a symbiotic relationship with UHC, helping them as much as they helped her. As early as July, 1893, when “Dr. Blumenthal of Madison Avenue performed an unusual operation” and “the United Hebrew Chari[ties]” was “in some dilemma” to find the proper care for the case, the nurses stepped in. The UHC, in turn, paid rent and moving costs when one of Wald’s patients, a “man with rheumatism,” needed to move from “a damp basement” to “sunnier rooms.” In August of the same year, the UHC paid costs so that a patient with lung disease could travel to Priory Farm, a home for convalescent men and boys in Dutchess County, New York. By August of 1893, Lillian Wald was able to highlight the mutually beneficial relationship between the nurses and the UHC in a letter to Schiff: We have “obtained relief” for “[m]any people…from the United Hebrew Charities,” she wrote, “—and Mr. Roseman is now in the habit of asking us to take a special case, where relief is needed….”

Schiff also asked the City’s Board of Health to provide “moral support” for the nurses’ endeavor. He arranged for Wald to meet “the President of the Board of Health,” whom she asked “rather presumptuously,” to “be given some insignia.” The President, “tolerant” of what Wald called her “intense earnestness,” agreed to allow the nurses to wear a badge proclaiming that they were a “Visiting Nurse. Under the Auspices of the Board of Health.” Wald returned the favor by keeping the City’s Health Department informed of her activities. She later remembered that, “Every night, during the first summer, I wrote to the physician in charge, reporting the sick babies and describing the unsanitary conditions Miss Brewster and I found….” In response, the nurses “received many encouraging reminders that what we were doing was considered helpful.”

Wald’s diligence again paid off. In an effort to increase school attendance, the Board expanded its relationship with the nurses, supplying Wald and Brewster “with virus points and authority to vaccinate, since no unvaccinated child could be admitted to school.” The nurses also aided the Board of Health in its campaign against tuberculosis. Persuading hospitals and dispensaries to give them the names of persons afflicted with the disease, Wald and Brewster visited the consumptives, provided them with sputum cups and disinfectants, and instructed them and their families on methods of hygiene that would minimize transmission of the disease. (Within a decade, the Board of Health took over this activity, employing nurses to provide this service.)

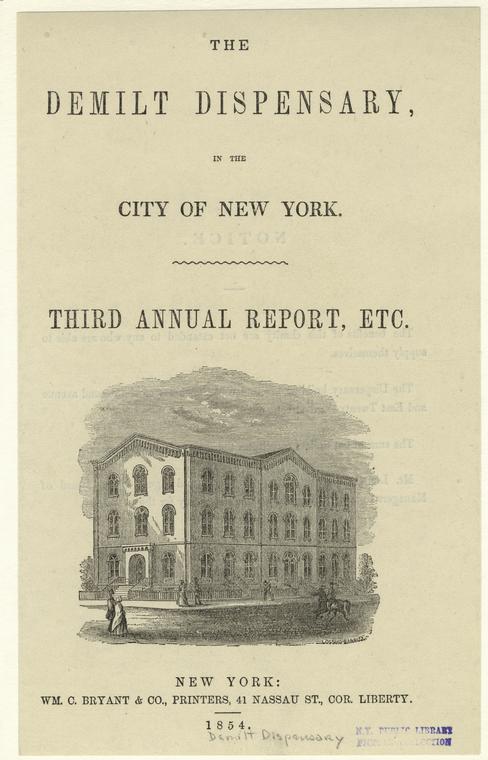

Wald also forged a relationship with Felix Adler’s Society for Ethical Culture. This group had been employing nurses to visit the sick poor since 1877, when the Society hired Effie Benedict, a Bellevue Hospital graduate, to work out of the DeMilt Dispensary under the supervision of the dispensary’s doctors. After the Society learned about Wald and Brewster’s work, they arranged for one of their paid nurses, Georgia Beaver [later Georgia Beaver Judson], to live and work with the two young women. Beaver Judson, a recent graduate of Mt. Sinai’s nursing school, “was the fourth nurse whom Miss Wald asked to join her,” the two others being Mary Brewster and Rebecca Shatz.” The women “all lived together” as “a happy family” in “the original” apartment. While Wald “had her own patients and cases,” Beaver Judson got her “patients from the dispensary of the Good Samaritan.”

Beaver Judson recalled that the nurses “were blessed with generous friends in those days–friends who supplied us with funds….” In addition to supporting the nurses, the donations supplied jobs to unemployed neighborhood women, who worked as aides, cooks, and cleaners for bedridden patients. The Women’s Conference of the Ethical Culture Society, which donated money to the nurses, had increased their contribution to twenty dollars a week by early March of 1894. Wald was able to use this money “employing women to clean the rooms of the tenements where illness takes us.”

Working out of the College Settlement on Rivington Street in the summer and fall of 1893, Wald secured monetary and in-kind donations from many other sources. Through frequent reporting, she made sure that her donors knew that their gifts were being used wisely, while also informing them in great detail of the dire need of the people she served. On July 7, 1893, Wald reported that they had “[b]rought clean dresses to the older children [of one family] and gave [them]…ice,” the latter provided by the New York Herald newspaper. She had to promise another family that, if the husband/father would agree to move and seek employment in the country or a less crowded part of the city, “we would give the children shoes and assist in their respectable appearance in their new home.” While giving her patients “excursion” tickets to a picnic sponsored by the Hebrew Sanitarium, she found that she also needed provide carfare and clothing to “make their decent appearance possible.”

Wald soon gained enough experience in the neighborhood to realize that some well-meaning but ill-informed donors made in-kind contributions that were ineffective or inappropriate. She did not hesitate to communicate her findings to them. In one instance she successfully asked “the editor of the Herald to substitute bread for ice because” some of her neighbors were so desperate and destitute “there was nothing to put on the ice….”

By the end of August, 1893 Wald was also in a position to assert her increasing acceptance and success in the neighborhood. She reported that she and Brewster had “obtained relief” for “many people” from “the United Hebrew Charities,” and that “Mr. Roseman” was “now in the habit of asking us to take a special case, where relief is needed.” She successfully negotiated with the University Settlement on behalf of another client, getting “him janitor work at five dollars a week.” For a fifteen-year-old runaway from Liverpool, Wald obtained bed and food at the Children’s Aid Society, bath at the Baron de Hirsch rooms, clean clothes from our store room, a ticket from the proper emigration agent, and in a very few days had him back to his parents in England.

She found work for Mrs. Jacobson, a homeless, unemployed mother of two, “for a few weeks as bed-maker at the Children’s Aid Society and found a place for the children while she worked.” Jennie Perk, another patient, proved too sick to continue “doing machine work,” and Wald promised to find her employment as a housemaid. When Samuel Shalinske’s wife died, “Miss Brewster’s people in Pennsylvania” found work for the grieving widower.

When Miriam Orshtigorirch “could get no work at her trade,” the young nurses bought her laundry “utensils” and found customers so that she could support herself and her child. They paid another woman to “scrub…and clean up” the apartment of a patient, found a job at New York Hospital “for a very needy woman,” and secured a place “at the Mount Sinai Training School [for Nurses] for a boy, who had been out of work many months and who needed to be taken from bad surroundings….” Wald even convinced one of her friends to pretend “to need a tutor for her son for a short time” in order to help a “Russian…bookworm” who wanted to be a teacher but was not yet ready to apply to college.

The powerhouse philanthropist Josephine Shaw Lowell was another of Wald’s early supporters. Wald later expressed her “intense gratitude for the part” Lowell “played” in her “early experimental days on the lower east side.” She recalled,

It was in the winter of ’93 when things were at high tension….she [Lowell] called upon me frequently offering to do all kinds of things, suggesting that she do ‘some of the errands’ that I might spare my strength for…caring for the sick and learning the neighborhood….

As was becoming her habit, Wald was careful to return Lowell’s kindness, ensuring that the two women forged a mutually beneficial relationship. Shortly after they first met, Lowell asked Wald to write a letter to the editor of a paper. Wald wrote the letter that same cold winter night, after a long day’s work, while sitting near the stove to warm her cold fingers. When “the letter was written,” she traveled down “the many flights of stairs” one last time that day to place it “in the post box,” to make certain that it reached its destination in a timely fashion.

Lowell also funneled support to Wald (and other groups) through the New York Charity Organization Society (COS) and the East Side Relief Work Committee (ESRWC), both of which she founded and helped to run. Wald was able to find work for some of her neighbors at the COS workroom and laundry, enterprises created between 1891 and 1897 in order to provide jobless women with training and wages. The ESRWC, established in the summer of 1893 to respond to a severe economic downturn that resulted in massive unemployment, raised enough money to begin a jobs program by the autumn of that year. The Committee negotiated with the City and other entities to create short term jobs, which the unemployed obtained by receiving “work tickets” distributed by philanthropic organizations, including the nurses. The jobs ranged from work in the garment industry to sweeping the streets to painting and cleaning the East Side’s filthy tenement buildings.

In giving out these tickets, Wald and other East Side philanthropists were able to connect thousands of men and women to jobs. On February 5, 1894, the New York Times reported that the Emergency Fund of the ESRWC “last week gave employment to nearly 1,500 persons (mainly heads of families) at street sweeping, sewing, nursing, scrubbing, and whitewashing.” A month later, on March 4, 1894, Wald reported to Schiff and Loeb that Mrs. Josephine Shaw-Lowell has increased our tailor shop privileges, so that now twelve men per week are from our patients’ families—those and eight on the street and the workers at the Delancey Street Sewing rooms and an occasional ‘lift’ besides from other sources bring us the most desirable means of relieving the households we enter.”

Wald made sure to keep in touch with her donors and supporters, responding promptly when they contacted her and always remembering their birthdays and anniversaries with calls and notes. Her thoughtfulness and enthusiasm led her to invite wealthy “uptown” donors, as well as other reformers, to visit her any time. They often took her up on her offer, and her hospitality soon became the stuff of legends. Her biographer Duffus noted that while Wald lived on Jefferson Street, up the stairs came such men as John Crosby Brown, Dr. Hermann Biggs, Dr. William H. Welch and the Flexners; such women as the beautiful Josephine Shaw Lowell, Jane Addams of Hull House, and Mary E. McDowell of the University of Chicago Settlement.”

Once, after a hard day’s work, Wald came home and to her surprise found “a well-known society woman seated in” their “little living-room.” Wald knew that on that particular day she had forgotten to leave the key with Mrs. McRae (her friend and the “janitress”). Upon inquiring, she found that the woman had gained access by climbing up the fire escape. Knowing that this method of access was “no slight venture and exertion for the inexperienced,” Wald remarked to McRae that there were certainly “more agreeable and safer” methods of getting into the apartment, even without the key. The janitress smiled, winked, and responded ‘it’s no harm at all. She’ll be havin’ lots of talk for her friends on this.’

During Wald’s first years on the Lower East Side, she carefully cultivated her talent for raising money from wealthy donors. Within a few years, she had become so skilled at fundraising that, a profile of her, written later in her life, stated that Miss Wald never asks anyone for money. Instead, with an embroidery of telling anecdote, she describes the need for more nurses. Or she depicts the pitiful straits of children without playgrounds, or the dismal makeshifts forced upon East Side society by its lack of decent halls for parties and weddings. One season a byword went round in rueful tribute to her persuasiveness: ‘It costs five thousand dollars to sit next to her at dinner.’”

Bibliography

Adler, Cyrus, Jacob H. Schiff: His Life and Letters, Garden City, NY: Doubleday, Doran and Co., Inc., 1929, vols. I & II

Bremner, Robert H., “Lillian Wald,” biographical entry in Notable American Women 1607-1950, Edward T. James, et. al, eds., v. 3, Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1971

Bullough, Vern and Bonnie, The Care of the Sick: the Emergence of Modern Nursing, NY: Prodist, 1978

Carson, Mina, Settlement Folk: Social Thought and the American Settlement Movement, 1885-1930, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1990

Cohen, Naomi W., Jacob H. Schiff: A Study in American Jewish Leadership, Hanover, NH: Brandeis University Press, 1999

Daniels, Doris Groshen, Lillian D. Wald: The Progressive Woman and Feminism, Ann Arbor: Xerox University Microfilms, c1976 (City University of NY, Ph.D., 1977.

“The Demilt Dispensary,” New York Times, Published: January 25, 1865

Duffus, R.L., Lillian Wald: Neighbor and Crusader, New York: The Macmillan Company, 1939

“Earnest Efforts to Aid the Poor. East Side Relief Work Committee’s Appeal—What Col. Murphy is Doing.” New York Times, Feb. 5, 1894

[Epstein], Beryl Williams, Lillian Wald: Angel of Henry Street [author’s name on title page is “Beryl Williams”], NY: Julian Messner, Inc., 1948

Friess, Horace L., Felix Adler and Ethical Culture: Memories and Studies, edited by Fannia Weingartner, NY: Columbia University Press, 1981

Lubove, Roy, The Progressives and the Slums: Tenement House Reform in New York City, 1890-1917, np: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1962

Smith, Helen Huntington, “Profiles: Rampant But Respectable,” The New Yorker, Dec. 14, 1929

“To Aid the Unemployed: New-York Crowded With Those Who Must Be Cared For. Mayor Asked to Accept Charities’ Commissioners’ Offer to Take Charge of Station-House Lodgers—Representatives of Charitable Organizations Believe This Would Rid the City of Those Not Entitled to Its Charity.” New York Times, December 23, 1893

Trachtenberg, Leo, “Philanthropy That Worked,” City Journal, Winter 1998 http://www.city-journal.org/html/8_1_urbanities-philanthropy.html Current June 1, 2015

Wald, Lillian D., The House on Henry Street, N:Y: Henry Holt & Co., 1915

Wald, Lillian D., Lillian Wald Papers, New York: New York Public Library, [1983]

Waugh, Joan, Unsentimental Reformer: The Life of Josephine Shaw Lowell, Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1997

Whelan, Anne, “Georgia Beaver Judson, a Pioneer with Lillian Wald; Little realized Inevitable Scope of Settlement Work,” The Bridgeport Sunday Post, June 4, 1939

Woods, Robert A. & Albert J. Kennedy, Handbook of Settlements (Russell Sage Foundation), NY: Charities Publication Committee, 1911

Woods, Robert A. and Albert J. Kennedy, The Settlement Horizon: A National Estimate, New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 1922

Yost, Edna, American Women of Nursing, Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott Co., 1947

Illustrations

Columbia University Library, “Child in Front of DeMilt Dispensary,” ca. 1900, Digital Collections Link to Illustration (Current 7/5/2020)

The DeMilt Dispensary, also get citation info, from NYPL: Link to Illustration (Current 7/5/2020)

U.S. National Library of Medicine, The DeMilt Dispensary, Images from the History of Medicine

Link to Illustration (Current 7/5/2020)

NYC Department of Records, Visiting Nurse, NY Municipal Records Early photograph of ill woman with shawl in rocking chair; visiting nurse seated next to her. Wedding portraits on wall

Ill Woman in a Rocking Chair

NYC Department of Records, Street Scene, Tenements, Probably Essex Street, between Grand and Hester Streets: A. Feinberg, Wallpaper at #36, private donation, 1880-1899.

NYC Department of Records, Street Scene, Worth Street and Five Points, Children playing in dirty snow banks; wagons, tenements and shops in background Kress Brewing Company, 1880-1899, private donation

Children Playing in Dirty Snowbanks

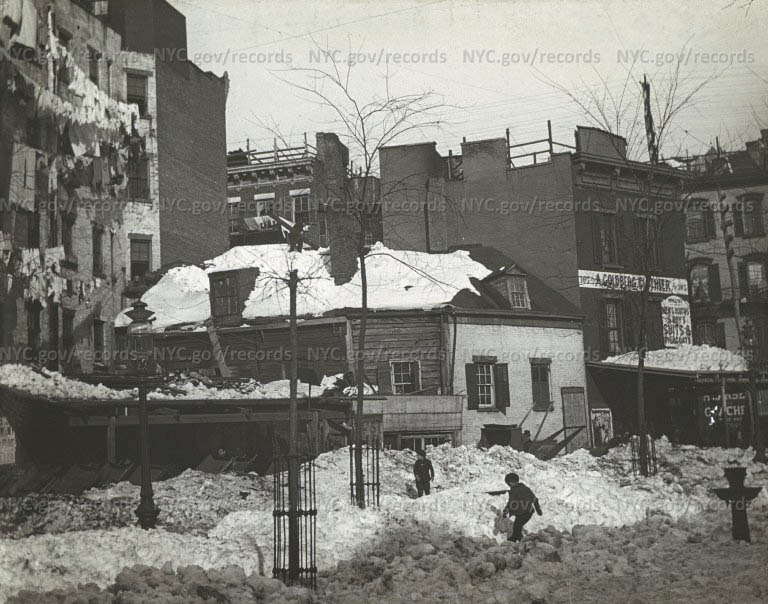

NYC Department of Records, Street Scene, Worth Street, West Baxter Street (Five Points), Children playing in deep snow banks. One-story house, tenements, “A. Goldberg, Clothier” on corner, 1880-1899, private donation

Children Playing in Deep Snowbanks

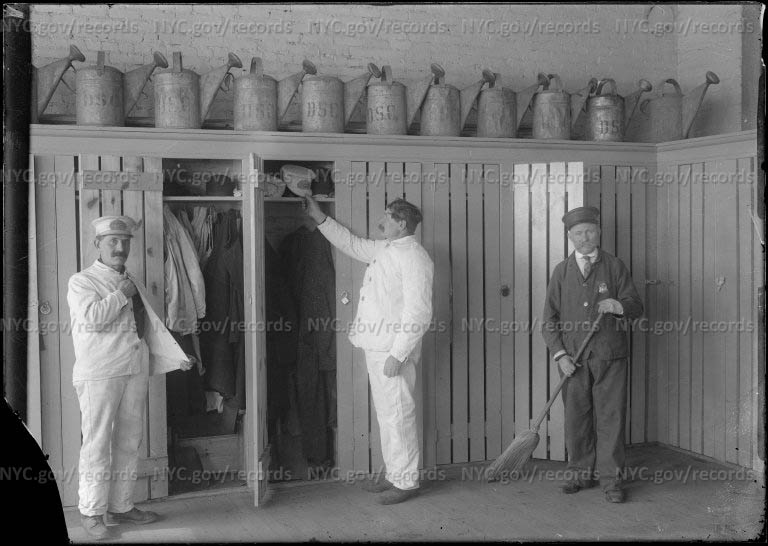

NYC Department of Records, DOS, Sanitation and Street Cleaning, DSC men in locker room. Open lockers, others shut. Row of sprinkler cans atop lockers, 1890-1910.

Sanitation and Street Cleaning Workers

NYC Department of Records, DOS, Sanitation and Street Cleaning, Summer Spraying on Tenement Street, nd

Summer Spraying on Tenement Street

Copyright Anne M. Filiaci 2016