FROM TREATMENT TO PREVENTION

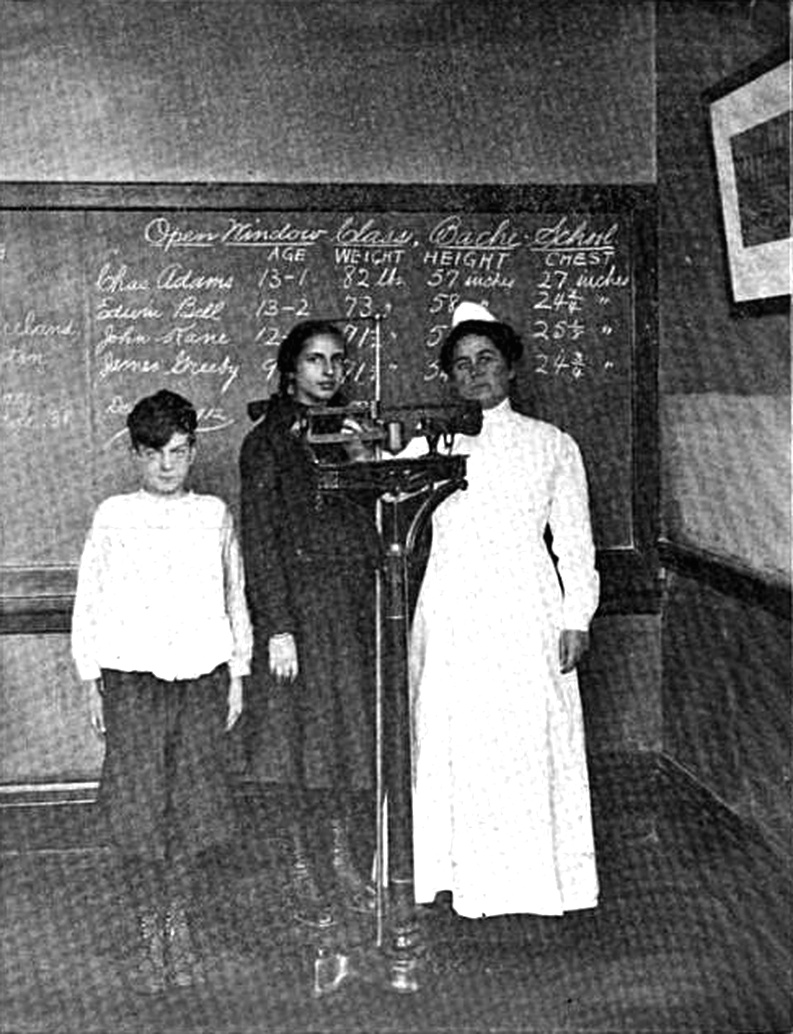

With the introduction of school nurses during Mayor Seth Low’s reform administration, the Departments of Health and Education made great strides in protecting the well-being of New York City’s school-age children. In a single year, 1905, fifty of the City’s school nurses, working alongside medical inspectors, examined a total of 1,351,083 school children in the public schools, treating 93,411. It had become plainly demonstrable that school nurses had a positive effect not only on the well-being of schoolchildren, but on New York City’s overall public health.

" order_by="sortorder" order_direction="ASC" returns="included" maximum_entity_count="500"]By 1908, the school nurse’s job had settled into a routine. Each nurse, “assigned to two schools of 2,000 children each,” reported to “the first school at 9 o’clock,” where until 11:00 a.m. she made “as many classroom inspections as possible.” From 11:00 a.m. until noon, she treated “all cases found during the inspection,” as well as those who came in “for daily dressing.” She also used this time to give “instructions” to those children who had conditions that did not require her hands-on treatment. The nurse repeated this activity in the second school each afternoon until closing at 3:00 p.m. At that time she began “home visits, five being considered the average for each day.” After her home visits, the nurse prepared a daily report and forwarded it to the supervising nurse. Only then could she consider her day complete.

But diagnosing and treating disease was only one part of creating a healthy school environment. The Department of Health still, for example, had “no control” over the “proper care of children’s outer garments at schools.” Since diseases and vermin could often be spread by contact with clothing, this was an important health issue. The garment problem was exacerbated by the lack of “proper aeration” of classrooms and by the fact that many children did not have easy access to running water and baths. Many children also lacked “sufficient” personal space and adequate “playground facilities.”

The Department of Health also had little or no control in areas relating to a school child’s health when contagion was not involved. Improper lighting of classrooms contributed to common eye problems. To exacerbate the problem, there was no way to examine and treat children’s eyes for “errors of refraction” (i.e. nearsightedness, farsightedness, and astigmatism)—problems confronted by “about 30 percent” of a selected sample of students. Nor was there any provision for the “examination and compulsory care of the children’s teeth and oral cavities.” School health officials also had little to say about excluding those with “nervous diseases” from class attendance, correcting the “deformity of locomotive apparatus,” and the “segregation of children with inferior mentality” —although Wald was, even then, busy conquering these problems thanks to the work of Henry Street Settlement resident Elizabeth Farrell.

Public health professionals had long known that because of these problems and many more, it was insufficient to limit their work to diagnosing and treating existing illnesses in the schools. By 1905, they were beginning to collect data and take actions to proactively prevent the spread of disease among students. That year, officials investigated schools “to ascertain what facilities existed…for the care of children’s outer garments [i.e. coats].” When they found that the “facilities were not the best,” they made “recommendation” for each child to “have a separate locker for its clothing” or, if this were not feasible, for children to store their “own clothing” in their desks.

Subsequent investigations examined the sharing of “writing and drawing utensils of the children,” since a “number of trachoma cases” had been “contracted by putting pencils in the eyes.” School medical inspectors filled out specific forms for each school under their care; on these forms they collected data on how many classes in each school assigned individual students envelopes to hold their supplies; how many used an “antiseptic pencil holder”; and how many used “individual boxes or bags.” They also noted classes where each child had “his or her own pencil” with “no collection or distribution at all”; the number of classes where “pencils are marked for identification but collected in a common box”; and the number of classrooms “in which pencils were “collected and distributed indiscriminately each day.”

These investigations found that fewer than half of school “principals and teachers took the slightest interest or concern” in “the matter of sanitary precautions in caring for these utensils.” Health professionals recommended that the “cheapest and best means” to remedy this situation was to provide each individual student with “a large manila envelope” in which to hold their school supplies. The envelopes, “marked with the child’s name” were to be distributed “at the beginning of class,” and would help to insure that each child would handle only his or her own supplies. The Department of Health endorsed the recommendation, furnishing envelopes “to all schools,” and requiring all teachers to keep a supply on hand.

The City also adopted other measures to prevent the spread of disease. The practice of having school nurses visit homes allowed them to discontinue the “old custom of sending a child to the home of” an absent schoolmate “to learn the cause” of the absence”— a custom that potentially put the healthy child at risk. Officials also burned school books that nurses found in the homes of children with contagious diseases. When contagious children had library books in their homes, these were “disinfected before they” were “returned to the library.” Each public library also received a daily list of students with contagious diseases, so that libraries might be careful when loaning out books.

Health professionals were now a permanent fixture in the schools. Amelioration had been successful. But a myriad of health problems remained. Reformers now turned to promoting the prevention of illness as well as minimizing its propagation. And they began to advocate for treating health issues that were not contagious but nonetheless affected a child’s ability to get a quality education in the public schools.

Bibliography

Darlington, Thomas, “Precautions Used by the New York City Department of Health to Prevent the Spread of Contagious Disease in the Schools of the City,” by Thomas Darlington, M.D., Commissioner of Health of New York City. From Medical News: A Weekly Journal of Medical Science, v. 86, no. New York, Saturday, Jan. 21, 1905, vol. 86, no. 3, pp. 97-104. Also available from Google Books at link

Mottus, Jane E., New York Nightingales: The Emergence of the Nursing Profession at Bellevue and New York Hospital 1850-1920 [Revision of thesis-Ph.D.), New York University, 1980], Ann Arbor, MI, UMI Research Press, c1981, 1980.

Rogers, Lina L. “Some Phases of School Nursing” by Lina L. Rogers, R.N. Supervising School Nurse, New York City. American Journal of Nursing, 1908, 8 (12), 966-974. (Re-printed with permission from the American Journal of Nursing, in Journal of School Nursing, October 2002).]

Illustrations

Farrell, Elizabeth, Photo/Portrait http://cecblog.typepad.com/.a/6a00d83452098b69e20167666511de970b-pi Current 1/31/17

School nurse weighing and measuring pupils, Philadelphia PA ca. 1912 This IMAGE (or other media file) is in the public domain because its copyright has expired. This applies to the United States, where Works published prior to 1978 were copyright protected for a maximum of 75 years. Works published before 1923 (in this case c 1913) are now in the public domain. Title: American journal of public health: the journal of the American Public Health Association, Volume 3, Issues 1-6. Author: American Public Health Association. Publisher: American Public Health Association, 1913. Original from: the University of California. Digitized: Aug 3, 2007. Subjects: Medical › Public Health Medical / Public Health, Public health

TEXT CREDIT: American journal of public health: the journal of the American Public Health Association, Volume 3, Issues 1-6 http://publicdomainclip-art.blogspot.com/2011/09/school-nurse-weighing-and-measuring.html Current 1/31/17

Hanink, Elizabeth, “Lina Rogers, the First School Nurse,” Working Nurse nd. Link to article with image http://www.workingnurse.com/articles/lina-rogers-the-first-school-nurse Current 1/31/17 Link to image only http://www.workingnurse.com/images/articles/big/webschool_nurse3_small.jpg Current 1/31/17

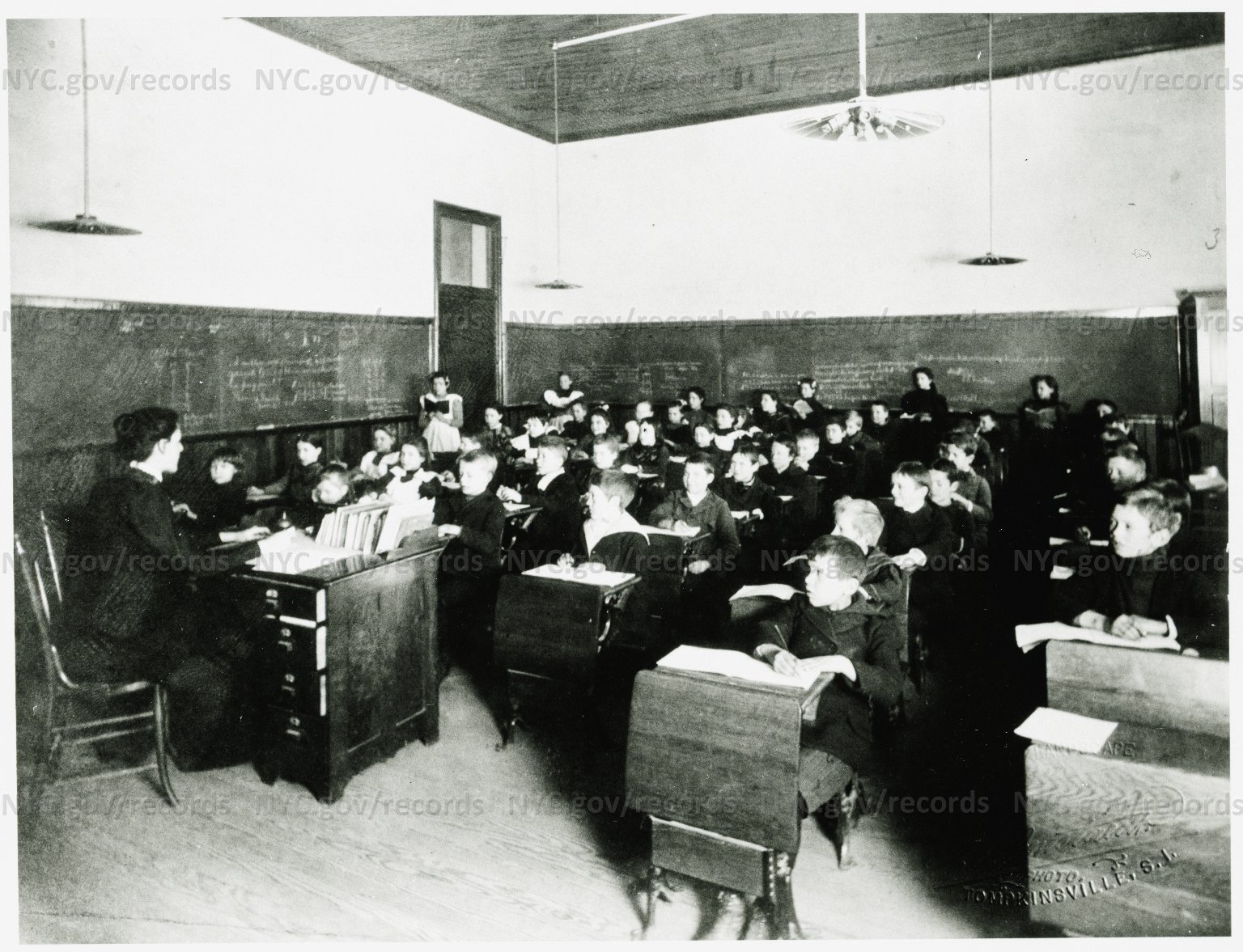

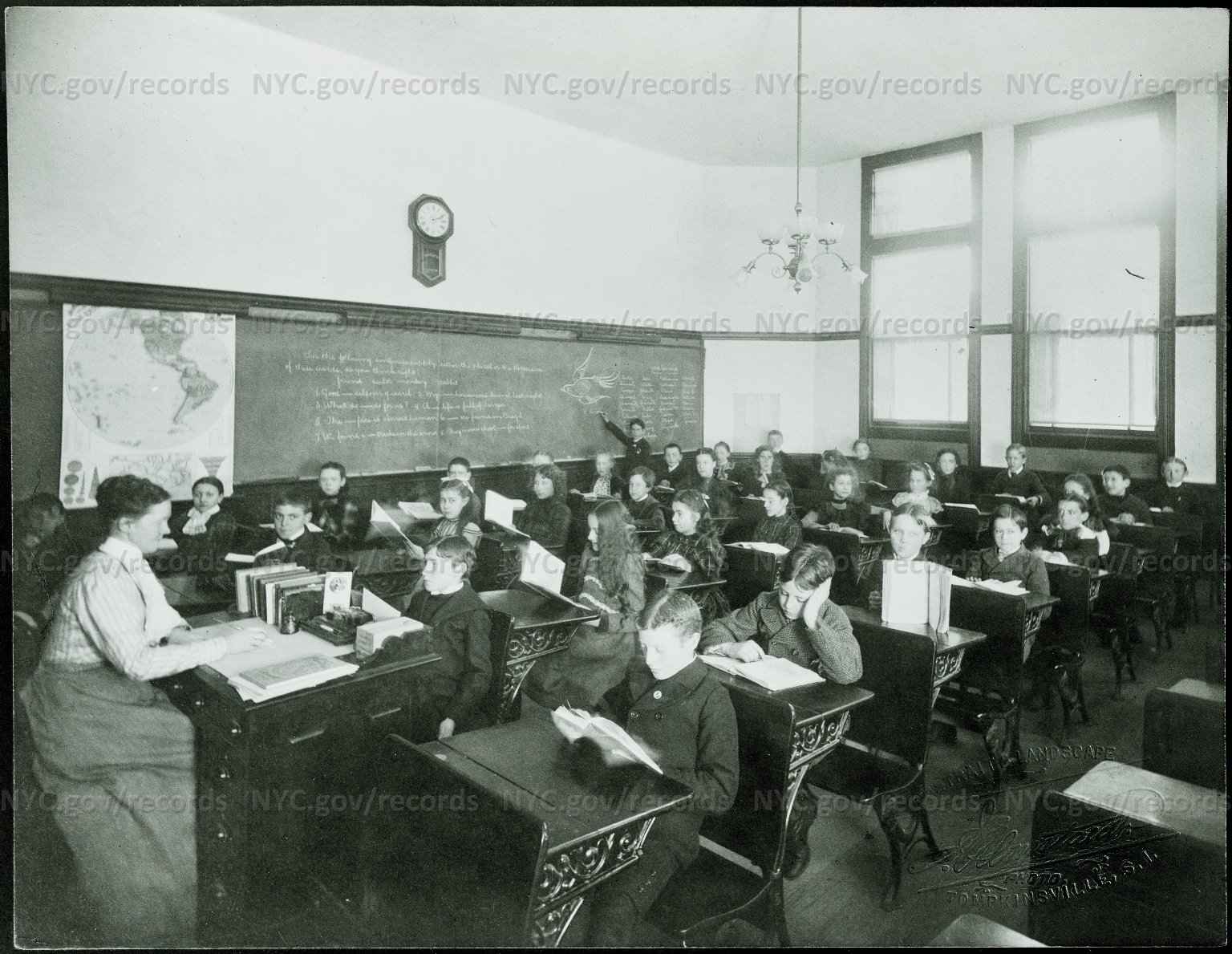

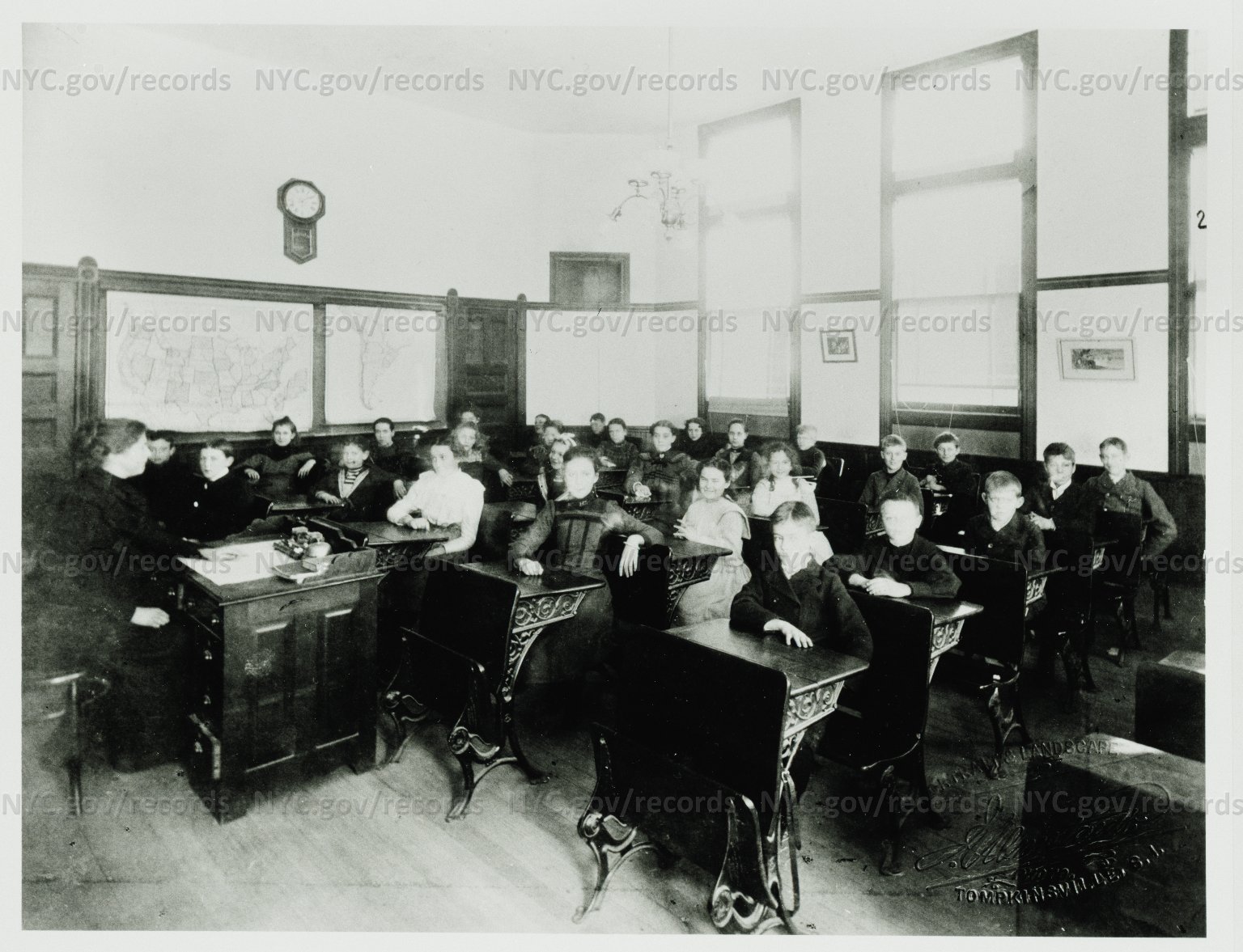

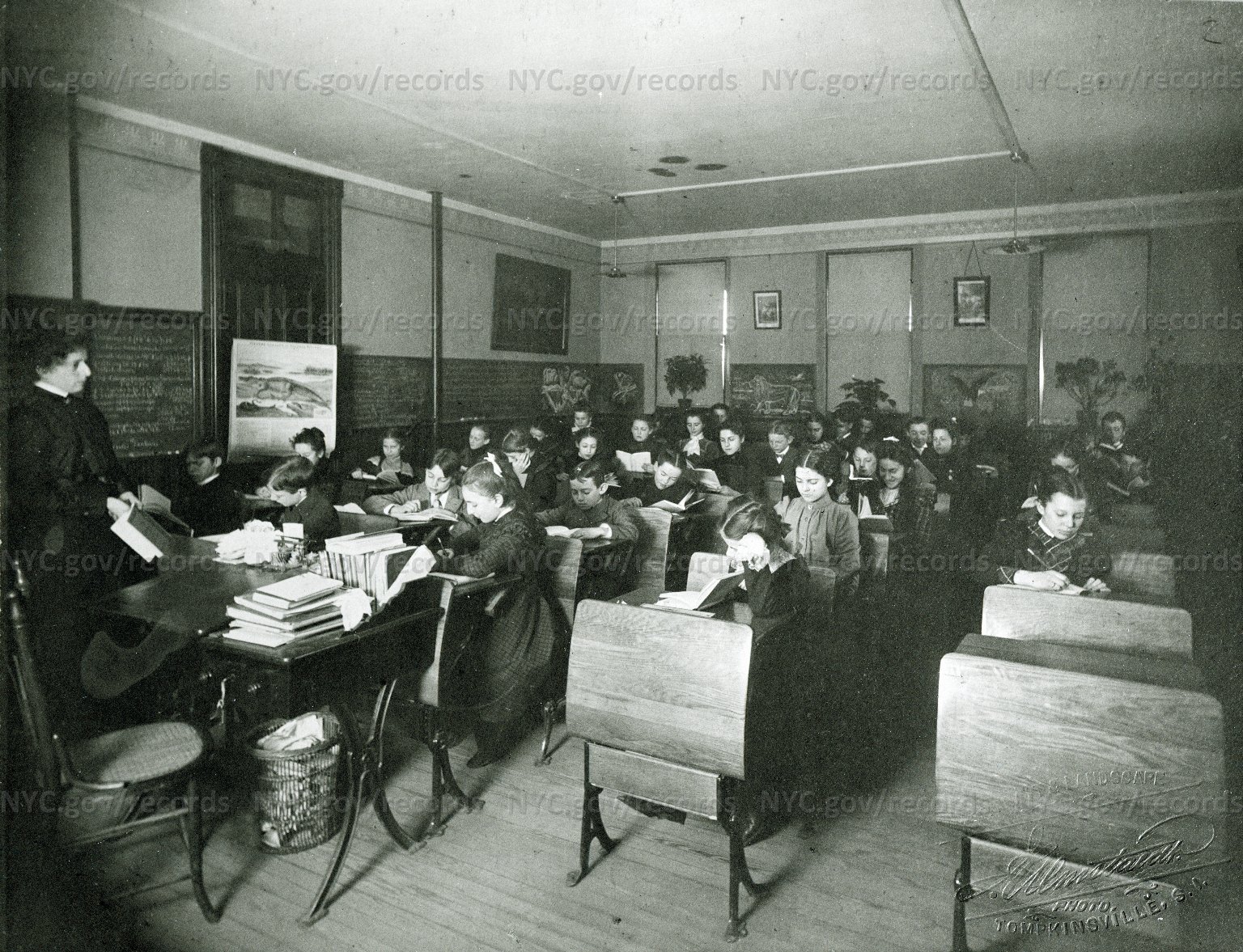

NYC DORIS, Board of Education, P.S. 10, Staten Island: classroom, 1900 (school id is tentative) Link to Illustration Current 1/31/17

NYC DORIS, Board of Education, P.S. 17, Staten Island: classroom, 1900 (school id is tentative) Link to Illustration Current 1/31/17

NYC DORIS, Board of Education, P.S. 16, Staten Island: classroom, 1900 (school id is tentative) Link to Illustration Current 1/31/17

NYC DORIS, Board of Education, P.S. 16, Staten Island: classroom, 1900 (school id is tentative) NYC DORIS, Board of Education, P.S. 16, Staten Island: classroom, 1900 (school id is tentative) Link to Illustration Current 1/31/17

NYC DORIS, Board of Education, P.S. 20, Staten Island: classroom, 1900 (school id is tentative) Link to Illustration Current 1/31/17

NYC DORIS, Board of Education, P.S. 15, Staten Island: classroom, 1900 (school id is tentative) Link to Illustration Current 1/31/17

Irma and Paul Milstein Division of United States History, Local History and Genealogy, The New York Public Library. “Recreation and hobbies – School activities – [Nursing – Public School No. 32, Brooklyn.]” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1902. http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47dd-a14a-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99 Current 1/31/17

Copyright Anne M. Filiaci 2016

< PreviousNext >