By Anne M. Filiaci, Ph.D.

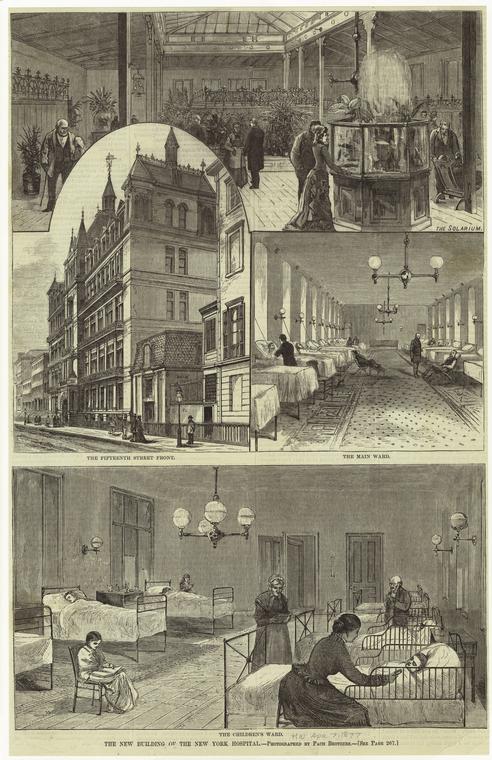

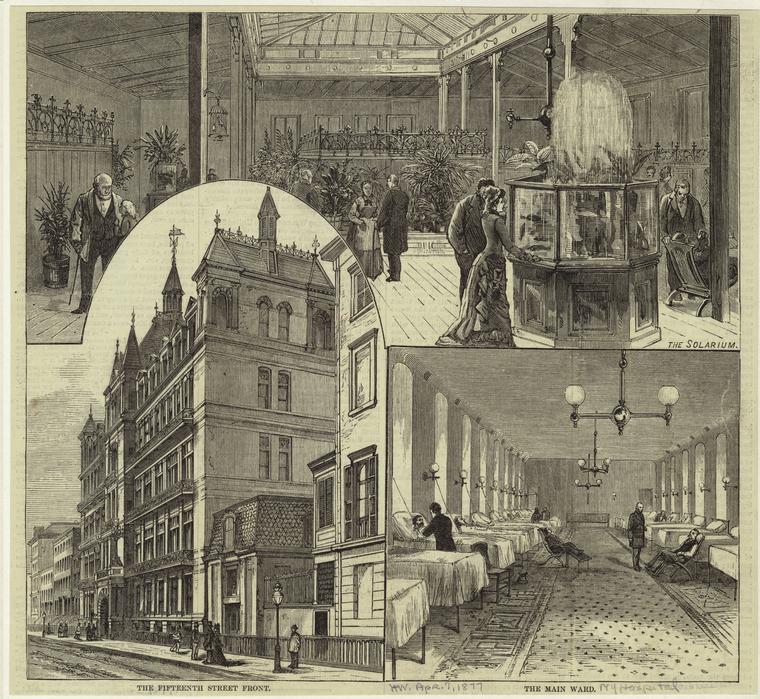

Lillian Wald entered the New York Hospital Training School for Nurses in August of 1889. Although the hospital had been in existence since the 1770s, the actual place where Wald was to study and work was relatively new. Located between Fifth and Sixth Avenues and Fifteenth and Sixteenth Streets, its inauguration ceremonies had taken place on March 16, 1877. The new hospital was “‘seven stories high, with a Mansard-roof, and…accommodations for about two hundred patients with their attendants.'” It contained new “‘appliances said to be found in no other public hospital in the world.'” These included “‘bell-wires and speaking tubes…placed throughout the building, and two elevators'” that “‘ran from the basement to the top story.'” The building had not only the usual wards but also private rooms with one or two beds, providing accommodation to out-of-towners who became sick while visiting the City.

" order_by="sortorder" order_direction="ASC" returns="included" maximum_entity_count="500"]The Hospital instituted a Nightingale-inspired nurses training program a few months after the inaugural, on July 9, 1877. Its first by-laws were revised less than a year later to state that “‘the course shall extend over a period of eighteen months,'” that it would “‘consist of twenty-four pupils, divided into classes of eight,'” and that applicants “‘must be between twenty-five and thirty-five years of age, and possess a good common school education.'”

The Nursing School dormitory was located in the Thorne Mansion, a building located near the hospital on Sixteenth Street, west of Fifth Avenue. It was crowded, unattractive and uncomfortable. Lydia Anderson, an 1897 graduate of the training school, described the common area as a place that was constantly busy:

“On the top story, was a very large solarium, fitted up with many plants, a tank with gold fish, and cages containing owls and doves. Here the convalescent men from the wards of the Hospital might come and smoke in the daytime, and here the nurses might receive their friends or listen to lectures from the doctors in the evening.”

This area, hectic as it was, seems delightful when compared to the student nurses’ actual living conditions. “Down a short flight of stairs from this bright room,” Anderson stated, “there opened, around a rotunda, some tiny rooms, lacking both light and fresh air.” This was where the nurses slept. Anderson recalled that once, when a doctor cared for a sick nurse in the dorm, he was so appalled that he “asked what the poor child had done that she should be kept thus in dark and solitary confinement.”

Those interested in maintaining and strengthening the reputation of the New York Hospital nurses training program had argued almost since the inception of the program that in order to attract quality nursing students, the hospital had to upgrade its accommodations. Their arguments were unsuccessful until the beginning of the year that Wald would enter the program. In his February 2, 1889 report, Hospital Superintendent George Ludlam wrote,

“‘It will be remembered that [our pupils] are women of refinement, accustomed to the comforts of good homes….Our school is the only one of these which is acknowledged to be the leading school of the country…without a Nurses’ Home. In view of the attractive homes provided by other schools, and the inadequate provisions of our own; it is a matter of constant surprise that women of such high character apply to us in such numbers.'”

A few days later, on February 5, 1889, the Board of Governors heeded Ludlam’s plea, passing a resolution to provide “‘adequate accommodations for the Training School for Nurses outside the Hospital.'” While Wald may have stayed in an interim rental building instead of the original dorm, unfortunately for her the new building would not open until the year she graduated.

Yet Wald was most likely too busy to pay much attention to her living conditions. Student nurses–who at the time did most of the nursing in hospitals–had little time to notice their surroundings. While Wald was studying there, New York Hospital admitted, treated, and discharged over 4,000 patients per year. During the same period, they graduated fewer than one hundred nurses. The hospital had grown from serving a little over 3,000 patients per year from 1879 to 1889, the year Wald entered, to an average of over 5,000 patients per year in the 1890s, the decade when she graduated. In 1878 the hospital had performed 142 operations, but by 1889, the year Wald entered, the number of operations had increased to 633.

The patients Wald treated would most likely be what was then termed “charity cases,” or people unable to pay the full cost of their stay. From 1878 until 1918, this type of patient made up between two-thirds and three-quarters of the hospital’s population.

Lillian Wald, still the headstrong and indulged child of Max and Minnie, did not find it easy to submit to hospital rules and procedures, especially when she believed they were unjust, irrational, or negatively affected patients. After she had been in nursing school only a few days, she was sent on an errand into the hospital’s basement. While there, she heard howls and screams and went to investigate. She entered a padded cell and found a wild-eyed man locked in there, suffering from delirium tremens. He begged her for food, which she was under orders not to supply. Yet, feeling only compassion for the man’s suffering, she ran up to an elevator boy whom she had befriended, told him of the patient’s plight, and convinced him to give her the keys to the diet kitchen. There she found food and brought it to the hungry man.

Instead of trying to hide her actions, the next morning Lillian approached Ms. Sutliffe directly to complain about the heartlessness of the hospital. Sutliffe made it clear that she did not condone rule breaking. She gave Lillian a gentle reprimand– “You should have asked permission to go into the diet kitchen.” But her supervisor also showed that she approved of the compassion shown by her young charge. She took the sting out of her rebuke by adding, “…I personally am glad that you fed that old drunk.”

Wald’s rule-breaking was relatively benign compared to the behavior of some student nurses. In the three years before Wald entered training school, one student had been asked to leave because of an opium addiction, another for being intoxicated, another for suspected theft and another for spending “‘several hours, until long after midnight, in the unlighted Operating Theatre'” with a doctor. However, there were circumstances under which Wald’s behavior could have been career threatening. In 1888, a graduate nurse was stripped of her diploma and her badge for complaining in a social situation that she believed a doctor had endangered the life of her friend. Perhaps because Wald was new, did not single out a specific doctor, and did not complain publicly, her actions were not considered serious enough to terminate her career.

Wald also had to overcome her squeamishness at witnessing the blood and gore of the operating room. Here, her compassion saved her. For the first few weeks of training, she resisted attending a surgery. But when one of her patients faced an operation, Sutliffe suggested, “I think she’d feel reassured if you went with her.” Wald put aside her own fear and abhorrence and accompanied the woman into surgery.

Most of Wald’s training consisted not of dramatic episodes like those above, but of routine chores like “bedmaking, removing of sheets and clothing and substituting fresh ones without disturbing or exposing the patient,…making …mustard plasters,…giving…an alcohol bath while the patient was in bed, bandaging, and cooking,….” In addition to her work with patients, she also spent a good deal of her time “cleaning…wards, washing…dishes, and polishing…brasses, of which the hospital had a super-abundant supply….” When Lillian was not caring for patients and working at other tasks on the ward, she attended lectures on anatomy, physiology, chemistry, hygiene, cooking and massage.

When middle-class and upper-middle-class young women began to enter the field of nursing, they initially resisted the idea of wearing uniforms. Soon, however, they took pride in doing so. During Wald’s tenure, the student nurses of the New York Hospital had a blue plaid uniform, ordered in Scotland by Miss Sutliffe exclusively for their use. The dress was accentuated by a long white apron, a cap, and a “soft white kerchief that went around….[the] neck and tucked in at the belt.”

Wearing a uniform was not the only thing that these women shared. In spite of the fact that Wald was somewhat younger than most of her classmates and the only Jewish woman in the school, she had much in common with the other student nurses. Most were American-born, and came from either New England or the Middle Atlantic states, with a good proportion coming from New York State. Their fathers, like Wald’s tended to be from the prosperous middle classes–over half were merchants, farmers, doctors, or clergy.

Most of the students in Wald’s class had, like her, completed a secondary education and had never been married. While some attended college, few had graduated. Having found a place where she belonged, Lillian Wald forged strong bonds with the other student nurses. Together they worked, studied, and relaxed. By the end of their training, they had become a self-described “sisterhood.”

Wald later recalled that she entered New York Hospital’s program “an undisciplined, untrained girl.” She described the course of her training as “strenuous,” but also “a wonderful human experience.” Graduated on March 31, 1891, she emerged from the program calm, assured, dedicated, and ready to help those who suffered–just like the nurse who had so impressed her in her sister Julia’s home.

Bibliography

Dock, Lavinia L., A Short History of Nursing: From the Earliest Times to the Present Day, In Collaboration with Isabel Maitland Stewart. NY: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1920

Duffus, R.L., Lillian Wald: Neighbor and Crusader, New York: The Macmillan Company, 1939

[Epstein], Beryl Williams, Lillian Wald: Angel of Henry Street [author’s name on title page is “Beryl Williams”], NY: Julian Messner, Inc., 1948

Feld, Marjorie N., Lillian Wald: A Biography, Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2009

Fondiller, Shirley H., Go, and Do Thou Likewise: A History of Cornell University-New York Hospital School of Nursing 1877-1979, New York: Cornell University-New York Hospital School of Nursing Alumni Association, Inc., 2007

Jordan, Helen Jamieson, Cornell University-New York Hospital School of Nursing, 1877-1952, [NY], The Society of the New York Hospital, 1952

Jordan, Pauline, “The Fiftieth Anniversary of the New York Hospital Training School for Nurses,” The American Journal of Nursing, Vol. 27, No. 6 (Jun., 1927), pp. 455-457, Published by: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Article Stable URL:http://www.jstor.org/stable/3409668 Current 7/8/11, includes photos Jordan NY Training School JSTOR June 1927

Lagemann, Ellen Condliffe, A Generation of Women: Education in the Lives of Progressive Reformers, Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1979

Mottus, Jane E., New York Nightingales: The Emergence of the Nursing Profession at Bellevue and New York Hospital 1850-1920, [Revision of thesis-Ph.D., New York University, 1980], Ann Arbor, MI, UMI Research Press, c1981, 1980.

Nutting, M. Adelaide and Lavinia L. Dock, A History of Nursing: The Evolution of Nursing Systems from the Earliest Times to the Foundation of the First English and American Training Schools for Nurses…In Two Volumes, NY: GP Putnam’s Sons, 1907.

Weir, Robert F., Personal Reminiscences of the New York Hospital From 1856 to 1900 [privately published by author?], Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2011 with funding from Open Knowledge Commons at http://archive.org/stream/personalreminisc01weir#page/n3/mode/1up Current 2/4/13

Yost, Edna, American Women of Nursing, Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott Co., 1947

Illustrations:

“RochesterCityHospital on West Main Street in 1877,” (date 1890-1910?). Rochester Public Library Local History Division Picture File, Rochester Images Database, Monroe County (NY) Library System, Postcard image at: Link to Illustration Current 1/29/13

Bellevue Hospital, Old-Time View of Blood Transfusion, 1890-1900, Detail View: DPC: Public Charities & Hospitals: dpc_0055, NYC Dept. of Records Link to Illustration Current 1/29/13

BellevueHospital, Nurses with little boys seated in cots. In foreground man is seated with little boy in his lap. 1890-1910. Detail View: dpc_0057 Public Charities & Hospitals, NYC Dept. of Records Link to Illustration Current 1/29/13

NYPL Digital Gallery, New York Hospital, 1878 Image ID: 805170 New YorkHospital. (1878) Link to Illustration Current 1/29/13

NYPL Digital Gallery, Private patient’s room, New YorkHospital. ([1878]) Link to Illustration Current 1/29/13

NYPL Digital Gallery, The New Building of the New York Hospital, 1877 Link to Illustration Current 1/29/13

NYPL Digital Gallery, The Solarium, Fifteenth Street Front, Main Ward, 1877, Link to Illustration Current 1/29/13

Copyright Anne M. Filiaci 2014