By Anne M. Filiaci, Ph.D.

Nursing School—The Decision

Julia Wald had reached the pinnacle of success for young upper-middle-class woman in late nineteenth century American society. She married into a family of wealth and prominence, and soon became a mother. Julia’s husband’s family earned its wealth in an attractive way–by growing flowers and selling seeds. The Barrys were reform-minded as well as prosperous. They went into real estate, building modestly-priced houses for their workers, and donated beautiful public spaces for the benefit of Rochester’s residents.

" order_by="sortorder" order_direction="ASC" returns="included" maximum_entity_count="500"]Yet it was not her sister Lillian Wald chose to emulate. It was the nurse whom Julia employed during her pregnancy. Lillian asked the Bellevue graduate to tell her everything about the career she had chosen. Although we do not know exactly what the woman said, we know that she described her training in great detail. If so, she would have told Lillian that student nurses worked very hard–generally twelve hours a day–and that their job consisted of many menial chores, such as scrubbing floors and cooking and serving meals for patients.

Young Lillian would also have learned that student nurses learned and performed professional and highly-skilled tasks. They made splints and bandages and dressed and cared for patients’ wounds. They studied anatomy and massage techniques. After observing their patients in a scientific manner, they made notes, recorded pulses and temperatures, and described in detail the diet and medication of each individual under their care. Doctors relied heavily on these observations to help diagnose and treat patients.

The successful student nurse witnessed the extreme pain of often delirious patients, the blood and gore of surgery, the death of some of her charges. As a result she emerged from training self-controlled, calm and composed even under the most extreme circumstances. Young Lillian saw this demeanor displayed in the nurse she met at her sister’s house. The headstrong and impetuous young woman, spoiled by her family and her circumstances, became convinced that nursing was the profession for her.

Once she had made up her mind, Lillian Wald had to persuade her parents that it would not ruin her life to reject–or at the very least postpone–marriage and motherhood. She also had to assure them that working in a hospital as a nurse would be safe and suitable employment for a respectable young woman of her background and upbringing.

This could not have been an easy task. When Max and Minnie Wald were young, hospitals were germ-ridden, filthy places. It was often dangerous and life-threatening simply to be a patient, because at the time little was understood about how diseases were spread. Doctors, nurses and orderlies did not know that they should wash their hands and their equipment before and after they operated. Because patients often got sicker, rather than better, when they went into hospitals, people widely assumed that hospitals were places where the poor went to die.

Even if hospitals had been more desirable places, the idea of their daughter becoming a nurse may have been hard for Wald’s parents to accept. Except for in those hospitals where women’s religious orders cared for patients, nurses in the first half of the nineteenth century were generally women from the lower rungs of society. The job was considered a form of servitude, and nurses were commonly ill-trained and often a danger to their patients. Some of the women who worked in hospitals as nurses were prisoners, forced to do the work as a part of their sentence. Often these women had been jailed because of drunk and disorderly conduct, and they were regularly caught using alcohol or drugs while on the job.

Hospitals began to change for the better during the last half of the nineteenth century. The discovery of anesthetics during the 1840s allowed surgeons to take more time and to be more careful during operations, cutting down on the number of patients who died during surgery. Yet even with this improvement, many still died of infections. Then, in the 1860s, Robert Koch and Louis Pasteur proved that diseases and infections were caused and spread by germs or bacteria. Joseph Lister, applying this “germ theory,” found that if you used antiseptics on instruments and patients before, during and after surgery, you could hold down the spread of germs and thus greatly reduce the risk of infection.

Scientists and medical professionals gradually adopted these new methods of disease prevention in hospitals. Lillian could argue with her parents that hospitals had become much healthier, safer places. But she still had to convince them that a woman could become a nurse and keep her good reputation. Julia’s nurse, being a Bellevue graduate, would have provided a good example. Bellevue’s Nurses Training School, established in 1873, was the first in the United States to be organized on the “Nightingale” model, a model that insisted all nurses trained under its auspices be “respectable” and well-educated women.

Nightingale-type programs in the United States followed the example set by Florence Nightingale, who had revolutionized nursing in England. Nightingale, who developed her methods during the Crimean War, believed that nursing was a noble calling and that nurses should be well-educated women of good character. She also asserted that only a trained, professional nursing staff could provide the proper hygiene and the clean environment that the best doctors and hospitals were beginning to demand. After the Crimean War ended, Nightingale found enough support and money to start her own nursing school in England, where she put her beliefs into practice with great success. Lillian’s parents did not need to visit England or even Bellevue to witness the changes in nursing education. Dr. William S. Ely, a prominent local physician, had been instrumental in starting a Nightingale-influenced nurses’ training program for the Rochester City Hospital in the summer of 1880. Aurora Smith, a Bellevue graduate, had designed the school’s curriculum.

Lillian and her parents could also find numerous other local examples of respectable women involved in health care. Just down the road from Rochester, in Danville, New York, Clara Barton had founded the American Red Cross. In October of 1881, Susan B. Anthony helped Ms. Barton to form its second branch, in Rochester. A few years later, in 1886, a group of Rochester’s women physicians–of whom there were now a substantial number–banded together to form and staff the Provident Dispensary, a health clinic for sick women and children.

Lillian was thus able to provide her parents with many examples of successful, respectable women who pursued professional careers in health care. And she was, as she herself said, a very “spoiled” and persistent young woman. So she persisted in making her case.

Whether or not Lillian’s parents were happy with her decision to become a nurse, in this, as in most other things, they not only indulged her, they gave her their support. She applied to nursing school.

Lillian Wald could have chosen to stay close to her family in Rochester and attend the nurse’s training school there. She noted that Dr. Ely had “most cordially desired me to join the Rochester training school.” But she chose instead to move away to New York City, but applied not to Bellevue, but rather to the New York Hospital Training School for Nurses.

New York Hospital had been chartered by George III on June 13, 1771. Its first years were marred by fire, scandal, and the chaos of the American Revolution. However, by the end of the eighteenth century it was beginning to attain a solid reputation. Dr. Valentine Seaman, who was the hospital’s attending surgeon from 1796 until he died in 1817, gave smallpox vaccines and instituted a regular nurses training that included lectures, ward experience, and maternity training.

When Wald applied for nursing school, New YorkHospital was at the forefront of the medical field. By the late 1860s, it had adopted the practices of sterilizing sheets, towels and surgical instruments and applying disinfectants to the hands of hospital staff. Staff also began to use masks during operations.

Wald explained why she chose New YorkHospitalTraining School for Nurses instead of RochesterCityHospital’s program in her application. She admitted that she was familiar with the Rochester program—even using Dr. Ely’s name as a reference—but announced that “should you accept me as a pupil, I would be more pleased, …because I have many social ties in Rochester, which might interfere with earnest, uninterrupted work there.”

Wald also offered, if she were accepted, to “make” herself “personally known” to the staff of the training school when she joined her “brother and sister–Mr. & Mrs. Charles P. [and Julia] Barry of Rochester, at the seashore [near New York City] some time in July….” True to her word, Wald visited the New YorkHospital that summer accompanied by her brother-in-law Charles. There she met with Miss Irene Sutliffe, a graduate of the Hospital’s School of Nursing who was now in charge. Miss Sutliffe took Lillian and her brother-in-law on a tour. While they were going through one of the children’s wards, Lillian, seeing a boy with his legs suspended in braces, could not help but shudder. Miss Sutliffe, noting the future student’s discomfort, said, “That boy is not suffering. He is a hero in the ward, and if you come here you and he will have great fun together.” Miss Sutliffe was already preparing her young charge to exhibit calm in the midst of suffering.

Bibliography

Armeny, Susan, “Organized Nurses, Women Philanthropists, and the Intellectual Bases for Cooperation Among Women, 1898-1920,” in Lagemann, Ellen Condliffe, Nursing History: New Perspectives, New Possibilities, NY: Teachers College, ColumbiaUniversity, 1983.

Bullough, Vern and Bonnie, The Care of the Sick: the Emergence of Modern Nursing, NY: Prodist, 1978.

Bullough, Vern L., and Bonnie Bullough, The Emergence of Modern Nursing, 2d ed., London: The Macmillan Co., 1969.

Bullough, Vern L., and Bonnie Bullough, History, Trends, and Politics of Nursing, Norwalk: Appleton-Century-Crofts, 1984.

Daniels, Doris Groshen, Always a Sister: The Feminism of Lillian D. Wald, New York, Feminist Press, 1989.

Davies, Celia, “Professionalizing Strategies as Time- and Culture-Bound: American and British Nursing, Circa 1893,” in Lagemann, Ellen Condliffe, Nursing History: New Perspectives, New Possibilities, NY: Teachers College, ColumbiaUniversity, 1983.

Dock, Lavinia L., A Short History of Nursing: From the Earliest Times to the Present Day, In Collaboration with Isabel Maitland Stewart. NY: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1920.

Dolan, Josephine A., Goodnow’s History of Nursing, Eleventh Edition, Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders Co., 1963.

Duffus, R.L., Lillian Wald: Neighbor and Crusader, New York: The Macmillan Company, 1939.

[Epstein], Beryl Williams, Lillian Wald: Angel of Henry Street [author’s name on title page is “Beryl Williams”], NY: Julian Messner, Inc., 1948.

Feld, Marjorie N., Lillian Wald: A Biography, Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2009.

Jordan, Helen Jamieson, Cornell University-New York Hospital School of Nursing, 1877-1952, [NY], The Society of the New York Hospital, 1952.

Lagemann, Ellen Condliffe, A Generation of Women: Education in the Lives of Progressive Reformers, Cambridge, Mass.: HarvardUniversity Press, 1979.

Lehr, Teresa and Philip G. Maples, To Serve the Community: A celebration of Rochester General Hospital 1847-1997, The Donning Company Publishers, 1997.

McKelvey, Blake, “Historic Origins of Rochester’s Social Welfare Agencies,” Rochester History, Vol. IX, Nos. 2 & 3, April, 1947.

Mottus, Jane E., New York Nightingales: The Emergence of the Nursing Profession at Bellevue and New York Hospital 1850-1920, [Revision of thesis-Ph.D., New York University, 1980], Ann Arbor, MI, UMI Research Press, c1981, 1980.

Nutting, M. Adelaide and Lavinia L. Dock, A History of Nursing: The Evolution of Nursing Systems from the Earliest Times to the Foundation of the First English and American Training Schools for Nurses…In Two Volumes, Volume II, NY: GP Putnam’s Sons, 1907.

Wald, Lillian, “Copy of letter sent by Lillian D. Wald to the New York Hospital in Applying for Admission to the School of Nursing. Mr. Ludlum was Superintendent of the Hospital. From Files of the CornellUniversity-New YorkHospitalSchool of Nursing. (Excerpts from this letter were read by Miss Dunbar at the Tea on March 10, 1952, the anniversary of Miss Wald’s birthday.) Dated “Fostoria, Ohio, May 27, 1889,” Lillian D. Wald Papers, New York Public Library.

Yost, Edna, American Women of Nursing, Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott Co., 1947.

Illustrations:

“RochesterCityHospital on West Main Street in 1877,” (date 1890-1910?). Rochester Public Library Local History Division Picture File, Rochester Images Database, Monroe County (NY) Library System, Postcard image at: Link to Illustration Current 1/29/13

Bellevue Hospital, Old-Time View of Blood Transfusion, 1890-1900, Detail View: DPC: Public Charities & Hospitals: dpc_0055, NYC Dept. of Records

Link to Illustration Current 1/29/13

BellevueHospital, Nurses with little boys seated in cots. In foreground man is seated with little boy in his lap. 1890-1910. Detail View: dpc_0057 Public Charities & Hospitals, NYC Dept. of Records

Link to Illustration Current 1/29/13

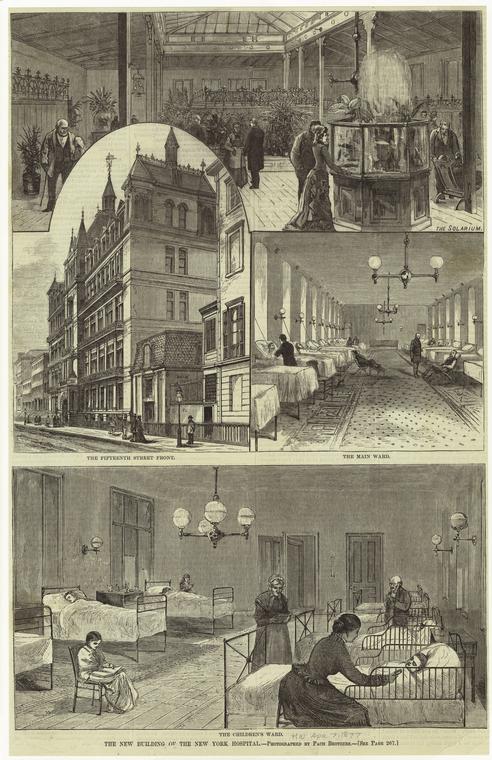

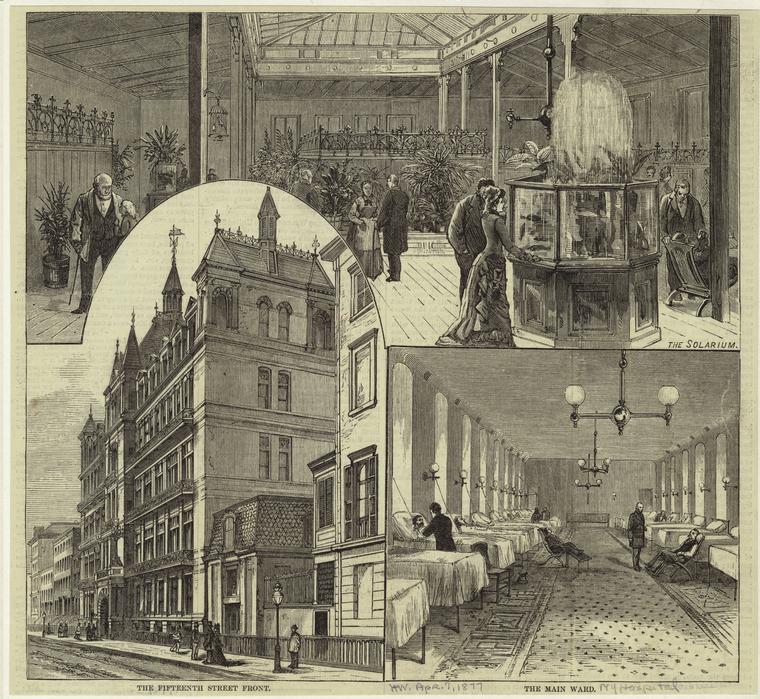

NYPL Digital Gallery, New York Hospital, 1878 Image ID: 805170

New YorkHospital. (1878)

Link to Illustration Current 1/29/13

NYPL Digital Gallery, Private patient’s room, New YorkHospital. ([1878]) Link to Illustration Current 1/29/13

NYPL Digital Gallery, The New Building of the New York Hospital, 1877 Link to Illustration Current 1/29/13

NYPL Digital Gallery, The Solarium, Fifteenth Street Front, Main Ward, 1877, Link to Illustration Current 1/29/13

Copyright Anne M. Filiaci 2016