By Anne M. Filiaci, Ph.D.

While visiting the sick in New York City’s tenements, Lillian Wald regularly encountered children who lived lives of constant toil. These children worked as household drudges, in sweatshops, as messengers, shoe shine and news boys, as cash girls, factory workers, and rag pickers—in short, in just about every menial job that existed at the time.

" order_by="sortorder" order_direction="ASC" returns="included" maximum_entity_count="500"]Wald, deeply affected by what she saw, soon joined with other like-minded reformers to advocate against child labor. By the end of the 1890s, Wald had formed a close, longstanding and effective alliance against child labor with one reformer in particular, Florence Kelley. Kelley, a well-known progressive activist and anti-child labor advocate, had by the turn of the century become Wald’s long-term housemate and a part of the Henry Street family.

As early as 1889, Kelley had published Our Toiling Children, an anti-child labor polemic replete with heartrending anecdotes buttressed by solid data. A significant portion of Kelley’s data for this book came from the 1880 U.S. census, which estimated that at least 1,118,000 children between the ages of ten and fifteen toiled in

As early as 1889, Kelley had published Our Toiling Children, an anti-child labor polemic replete with heartrending anecdotes buttressed by solid data. A significant portion of Kelley’s data for this book

“every conceivable industry: glass and electric light works; silk, cotton and woolen mills; rubber, brick and pottery works; manufactories of wallpaper, snuff, cigars, shirts, crackers, baskets….”

Our Toiling Children asserted that the census actually underestimated the number of “wage-earning children… in the United States.” This was in part because so many children were employed in their homes, rendering their labor virtually invisible to most outside observers. (Kelley, Our Toiling Children, 1889, p.4.) Kelley supported her assertion with state reports, where she found that “[t]he children of clothing-makers in New York City begin work” as early as “four years of age, their labor power being available, under the sweating system of tenement house manufacture, for picking out basting threads.” (Kelley, Our Toiling Children 1889, pp.3-4, Blumberg, Florence Kelley, pp. 99-100, citing Our Toiling Children.)

In a piece written more than fifteen years later, Kelley elaborated on the ways that very young workers toiled in tenement homes. In addition to “picking out basting threads,” she wrote, they were employed to “sew on buttons, paste boxes and labels, strip tobacco and perform a multitude of simple manipulations….” They could handle these tasks, she added, “as readily as they can learn the kindergarten occupations.” (Kelley, Ethical Gains, 1905, pp. 7-8)

Kelley also used eyewitness testimony to drive home her point about the ubiquity of child labor in the home. She quoted the 1884 testimony of Brooklyn journalist Theodore Gruno, who reported that while visiting tenement “houses” where “sanitary conditions” were “terrible,” he had “seen children from four to six years of age sitting on the floor…pulling threads out of clothing.” (Kelley, Our Toiling Children, 1889, p. 19, quoting Commissioner C. F. Peck, Report of the Bureau of Labor Statistics of New York, 1884.)

Kelley also shared the testimony of a thirteen- or fourteen-year-old girl who had worked in the “tailoring” business for “nearly a year….” The girl stated,

“‘I work on a sewing machine; I have been in tenement houses and seen children seven to twelve years of age at work. * * * Sometimes two or three are employed in each shop. When busy, they work from 7 o’clock in the morning till [sic] 9 o’clock and sometimes till 10 o’clock at night. The children pull out basting threads. Some work by the piece, and the regular price is two coats for a cent.’ (Kelley, Our Toiling Children, 1889, p. 23) In the same year, a number of cigar workers testified, giving valuable information about”

In the same year, a number of cigar workers testified, giving valuable information about the centrality of child labor to their work. Some of their statements are quoted in Figure A, below.

Figure A

Cigar Workers testimony

Report for the Bureau of Labor Statistics of New York, 1884, by Commissioner C.F. Peck, (pp.171,162,181,180,148, quoted & cited in Kelley, Our Toiling Children, 1889, pp. 19-21)

“‘All the children in tenement houses work. I have seen those of nine and ten years old at work.’

‘I have seen children employed in tenement house cigar factories varying in age from six years, I should say, to fourteen; they have been kept from school and been obliged to work almost any length of time without any regulations as to time, and barely have time to go through with their meals….’

‘I have seen eight persons working in one small room about twelve by fourteen. One of the eight was a little fellow not more than nine years old, indescribably dirty and ragged.’

‘In busy seasons you can see any number of children engaged in stripping and preparing tobacco; the number so employed would average more than twenty to a house, and the ages would range from five to fourteen; they work from eleven to fourteen hours a day, sometimes more. They do not work as long hours as the grown people but enough to kill them rapidly.’

‘The children in our trade are pressed into service from the time they are nine years of age, and from then on they work pretty steadily until they reach an age at which to assume the responsibilities of manhood and womanhood. I very well remember one tenement house where manufacturing was carried on. * * * The building was used as a tenement house factory, and was inhabited by families numbering on the average about five or six members. * * * Most of these families occupied two rooms * * * These two rooms served as the workshop, and, of course, dwelling; in most cases there would be no ventilation…. They get a certain amount of tobacco from the foreman, enough to do a week or half a week, as the case may be, and that is prepared by the children for the parents to work up; the tobacco lies around the floor, and the workshop and the kitchen are in the same room. If once any of it accumulates, it begins to sweat, and the rankness of it is carried off through the air; then add to that the steaming stew kettle on the stove, where the woman is about preparing dinner, and you can imagine what the ventilation must be….’

‘In another house the children were sitting on the floor dirty and filthy; they were drying tobacco on the bed for fillers; in general I found these places to be without ventilation….’”

Jacob Riis—Wald’s close friend and mentor since her earliest days on the Lower East Side—was another partner in her fight against child labor. Riis achieved fame as a muckraking journalist with his groundbreaking work How the Other Half Lives, published in 1890. He followed up in 1892 with an expose of child labor entitled Children of the Poor. The latter relied on heart-wrenching personal anecdotes, generously illustrated with photos Riis himself had taken of the children he met.

Riis’s book, like Kelley’s, described labor as a near constant in the lives of New York City’s poor children. “In nine tenements that were filled with homeworkers,” he wrote, “we found five children at work who owned that they were under fourteen. Two were girls nine years of age. Two boys said they were thirteen. (Riis, Children of the Poor, p. 95) Visiting and informally polling “an evening school class of nineteen boys and nine girls,” Riis found that

“one twelve-year-old girl sewed coats in a sweat-shop…. The four smallest girls were ten years old, and one of them worked for a sweater and ‘finished twenty-five coats yesterday’ she said with pride…. The three others minded the baby at home; one of them found time to help her mother sew coats when baby slept. (Riis, Children of the Poor, p. 111.)”

The home workers that Riis and Kelley studied made or finished most if not all small products that did not require machinery or skilled labor, including clothing, artificial flowers, costume jewelry, lace, cosmetics and hair accessories, cigarettes and more. (Trattner, Crusade for Children, p. 146).

Wald’s own early experiences on the Lower East Side echoed the studies and observations of Kelley and Riis. As a visiting nurse, Wald daily confronted a system that thrived on children doing tedious work for long hours and low wages in dirty, overcrowded, poorly ventilated and disease-ridden rooms. Looking back in 1915, she reminisced that

“when we went from house to house caring for the sick, manufacturing was carried on in the tenements on a scale that does not exist today. With no little consternation we saw toys and infants’ clothing, and sometimes food itself, made under conditions that would not have been tolerated in factories, even at that time. (Wald, House, pp. 152-153)”

Jacob Riis, using his considerable skill for plucking at the heartstrings of readers, told his audience the story of one little girl with a grave illness that, while preventing school attendance, did not preclude sweatshop work. He wrote,

“…since the sewing machine found its way, with the sweater’s mortgage, into the Italian slums also, little Antonia…has taken her place among the wage-earners when not on the school-bench. Once taken, the place is hers to keep for good. Sickness, unless it be mortal, is no excuse from the drudgery of the tenement. When, recently, one little Italian girl, hardly yet in her teens, stayed away from her class in the Mott Street Industrial School so long that her teacher went to her home to look her up, she found the child in a high fever, in bed, sewing on coats, with swollen eyes, though barely able to sit up. (Riis, Children of the Poor, p. 21)”

Like Riis, Wald also encountered the phenomenon of children forced to work while ill. “One Thanksgiving Day,” she wrote,

“I carried an offering from prosperous children of my acquaintance to a little child on Water Street whose absence from the kindergarten had been reported on account of illness. He had chicken-pox, and I found him, with flushed face, sitting on a little stool, working on knee pants with other members of the family. (Wald, House, pp. 153-155)”

Healthy children were, of course, even more productive. Riis tells the story of “Little Susie,” whose job of “pasting linen on tin covers for pocket-flasks” was “one of the hundred odd trades, wholly impossible of classification” that “one meets with in the tenements of the poor.” Riis took Little Susie’s picture as she pasted the linen, but her “hands” were “so deft and swift that even the flash could not catch her moving arm, but lost it altogether….”

Riis went on to describe Susie as

“a type of the tenement-house children whose work begins early and ends late. Her shop is her home. Every morning she drags down to her Cherry Street court heavy bundles of the little tin boxes, much too heavy for her twelve years, and when she has finished running errands and earning a few pennies that way, takes her place at the bench and pastes two hundred before it is time for evening school. Then she has earned sixty cents—‘more than mother,’ she says with a smile. ‘Mother’ has been finishing ‘knee pants’ for a sweater, at a cent and a-quarter a pair for turning up and hemming the bottom and sewing buttons on; but she cannot make more than two and a-half dozen a day, with the baby to look after besides.” (Riis, Children of the Poor, pp. 109-110) (Image of Susie is at p. 110)”

Riis was quick to point out that when it came to a life of labor, “Little Susie” was no different from most—if not all—of the children she knew—

“Of Susie’s hundred little companions in the alley—playmates they could scarcely be called—some made artificial flowers, some paper-boxes, while the boys earned money at ‘shinin’’ or selling newspapers.” (Riis, Children of the Poor, p. 111)”

Sometimes, especially when there was a sick or an absent parent, the labor of children in tenements not only supplemented the family income but ended up being the majority of its weekly wages. Riis observed that

“In nearly every instance observed by Dr. Daniels [Anne Daniel] the children’s wages, when there were working children, was the greater share of the family income. A specimen instance is that of a woman with a consumptive husband, who is under her treatment. The wife washes and goes out by day, when she can get such work to do. The three children, aged eleven, seven, and five years, not counting the baby for a wonder, work at home covering wooden buttons with silk at four cents a gross. The oldest goes to school, but works with the rest evenings and on Saturday and Sunday when the mother does the finishing. Their combined earnings are from $3 to $6 a week, the children earning two-thirds. The rent is $8 a month.” (Riis, Children of the Poor, p. 101)”

As a result of their observations, studies, and daily visits to the poor, Wald, Kelley and Riis learned that “[w]hen work is carried on in the home, all the members of the family can be and are utilized without regard to age or the restrictions of the factory laws.” (Wald, House, pp. 153-155) The three reformers, along with many other Americans, would come to argue that the tenement or sweatshop system deprived its child workers of a decent education, good health, and any form of hope for the future. (Trattner, Crusade for Children, p. 146)

Reformers like Wald, Riis and Kelley continued to use anecdotal evidence and other accumulated data to make their case on the evils of child labor to the lives of young workers. But they soon began to widen the scope of their criticism, claiming that the institution of child labor affected not only the individual workers, but also the well-being of American society as a whole. Reformers pointed out that literacy was essential to the success of a self-governing republican form of government, and that a universal public education was key to ensuring the maximum number of literate adults. They saw the tenement or sweatshop labor of children as a major factor in undermining their attempts to make universal education a reality. Kelley asserted that

The noblest duty of the Republic is that of self preservation by so cherishing all its children that they, in turn, may become enlightened self-governing citizens.” (Kelley, Ethical Gains, 1905, p. 3)

. Wald gave numerous accounts of eyewitness evidence that tenement sweatshop labor often kept children from learning. She wrote that

Examination of the school attendance of children who do home work bears testimony to its relation to truancy. Josephine, eleven years of age, stays out of school to work on finishing; Francesca, aged twelve, to sew buttons on coats; Santa, nine years old, to pick out nut meats; Catherine, eight years old, sews on tags; Tiffy, another eight-year-old, helps her mother finish; Giuseppe, aged ten, is a deft worker on artificial flowers.” (Wald, House, p.155)

Wald also revealed that one day, a child came “for help to the nurse at the First Aid Room at the settlement.” When the nurse discovered that “his head showed evidence of neglect” (in other words, he had lice), she asked how his condition had “escaped” the attention of the school’s medical inspectors. His response (or lack of it) made it obvious to her that the boy “had never been in school.” Further immediate “inquiry…revealed” the existence of “a basement sweatshop” where “five children” who lived there “engaged in making paper bags which the mother sold to small dealers.” None of the five children, “all of whom had been born in America, had ever been to school.” When settlement workers “reproved the other children in the tenement for not having drawn…attention to their little neighbors, they answered that they themselves had not known of the existence of” the five children “because ‘they never came out to play.’” (Wald, House, p. 155-156, story retold in Wald, Windows, pp. 195-196)

Kelley illustrated the ill effects of home work and child labor on education in a story that took place even after child labor laws had gone into effect—

in the spring of 1903, a kindergartner [teacher] in New York City, on missing from her class an Italian brother and sister aged four and five years, and visiting them in their homes was told by their mother that they could not be spared from their work to go to the kindergarten. They were engaged in wrapping colored paper around pieces of wire, to form the stems of artificial flowers which the family manufactured in their tenement home, the older sisters making the leaves and petals, and the other members of the group forming whole flowers and sprays.” (Kelley, Ethical Gains, 1905, pp. 6-7)

Existing laws supposedly forbidding this type of child labor could not help in this situation, because of the numerous loopholes in the legislation. When concerned adults brought the matter to the attention of a school “attendance agent,” they were informed that, under the law of 1903, the children were “exempted” from attending school until their “seventh birthday.” When reformers then brought the matter to the “attention” of the “factory inspector,” he

observed that the case did not appear to constitute a violation of the factory law, since the children were not receiving wages, and the group at work did not exceed the number authorized under the license to manufacture artificial flowers in their tenement home. (Kelley, Ethical Gains, 1905, pp. 6-7)

When goods had to be transported from jobber to tenement workers, Kelley later wrote, some children “were sacrificed by being kept from school to serve as beast of burden, whenever the goods are such as can safely be trusted to a child.” (Kelley, Ethical Gains,1905, p. 24) In an effort to raise awareness—and no doubt to poke at the conscience of her (mostly female) audience, Kelley gave a speech in Ohio where she noted that

yesterday, on the street here in Cincinnati, I saw a very small boy carrying home frames and lining, and velvet, for what were evidently going to be very good-looking bonnets for the women in Cincinnati to wear. They will have been finished under the sweating system.” (National Child Labor Committee, Report, Jan. 1907, pp. 178-179

Other investigators amplified the horror stories of youngsters who worked. They found children as young as three straightening tobacco leaves, and four-year-old youngsters putting covers onto boxes. A Consumers’ League investigator found to her horror that a seven-year-old girl had been paralyzed as a result of her never-ending labor in a tenement sweatshop. The youngster had been working since she was three, “‘day after day with little legs crossed, pulling out bastings from garments.’” Her constantly-crossed legs, combined with lack of movement, had caused the girl’s paralysis. (Lubove, Progressives, p. 210).

Mary Van Kleeck, Secretary for the New York Committee on Women’s Work, published a report in 1910 that outlined how these atrocities continued even after decades of attempts by reformers to end child labor in tenements. The report, entitled Child Labor in Home Industries, noted that, as Kelley described above, one could easily observe underaged children “who would not be permitted to enter a factory” in the streets “carrying bundles of clothing or boxes of artificial flowers from work-shop to home.” Once inside the tenement sweatshop—this one located on Thompson Street—an investigator employed by the committee found

a mother and four children making artificial flowers. The oldest girl was eleven years old. Her sister was nine, her little brother was seven, and a little sister was five. The three older children had just come home from school, but the youngest child was too young to go, and worked all day separating the petals of artificial flowers. The oldest child of eleven years was deformed. She was not larger than a child of five. (Van Kleeck, Child Labor, 1910, p. 145)

The investigator also learned, upon questioning the workers, that

mother and children work until ten or eleven o’clock at night, and what they do not finish at night they must get up in time to finish in the morning before school begins. The little girl, Angelina, said she did the work the teacher gave her to do at home before school in the morning. “This morning, first I did the writing,” she said, “then I did the two times, and then the three times, so I won’t have so much to do.” (Van Kleeck, Child Labor, 1910, p. 145)

School seemed almost like a vacation to children like Angelina, who also told the investigator, “I like school better than home. I don’t like home. There’s too many flowers.” (Van Kleeck, Child Labor, 1910, p. 146)

Kelley acerbically described the situation—

The children whose school life is sacrificed to the need of being on hand to fetch and carry are losers, pure and simple. So are the wretched little boys and girls who are still too young to fetch and carry, but can be employed in stringing beads and pulling out basting threads, in pasting boxes and bags, in wrapping paper around strips of wire to make stems for artificial flowers, in digging the kernels out of nuts, or in cracking the nuts themselves.” (Kelley, Ethical Gains, 1905, p. 48)

Wald echoed Kelley, if less provocatively, summarizing the ill-effects of child labor on the later success of individual workers and society:

We know that physical well-being in later life is largely dependent upon early care, that only the exceptional boys and girls can escape the unwholesome effects of premature labor, and that lack of training is responsible for the enormous proportion of unskilled and unemployable among the workers.” (Wald, House, p. 133)

In addition to their writing, reformers like Kelley, Riis and Wald took their poignant stories on the lecture circuit and into the banquet halls and drawing rooms of their wealthy friends. From there they gained access to legislative chambers and state houses. At his talks, Riis showed lantern slides of the photographs he took. Kelley, by all accounts a dynamic and compelling speaker, addressed women’s groups around the country, rousing them to take action in their communities. Wald was adept at convincing her ever-widening circle of wealthy philanthropist friends and donors to use their considerable political weight—as well as their money—to support the cause of abolishing child labor.

By 1904, Wald’s mentor Jacob Schiff, a businessman and philanthropist who had financially backed her and the Henry Street Settlement from the beginning, admitted that Wald had influenced him to take action as an ally on the subject of child labor. While he considered himself to be much more conservative than most progressives, he too believed, like Wald, Kelley and others, that standing up against child labor not only helped individual children but furthered the goals of the republic. In a letter he wrote that year to Ethical Culture leader Felix Adler (title), he stated that

‘My heart, I need not tell you, is, like yours, in the cause of the children, both for sympathetic and practical reasons, for we cannot expect that the future American race be sturdy, if we permit the health and the morals of the child to be undermined.’ (Adler, Jacob H. Schiff, I, p. 296)

Through their hard work, persistence and advocacy during the waning years of the nineteenth century, progressive reformers like Wald, Riis and Kelley succeeded in broadening support for the cause against child labor. They did so with a growing number of firm allies—from grass roots community-minded citizens in towns and cities across the country, to academics, politicians, and wealthy movers and shakers who knew how to negotiate political thickets and get legislation out of committee, passed, and signed into law.

Bibliography

Adler, Cyrus, Jacob H. Schiff: His Life and Letters, Garden City, NY: Doubleday, Doran and Co., Inc., 1929, vols. I & II. Schiff to Professor Felix Adler, January 22, 1904, I p. 296.

Blumberg, Dorothy Rose, Florence Kelley: The Making of a Social Pioneer, New York: Augustus M. Kelley, 1966, pp. 99-100, 163, 165-169.

Bradbury, Dorothy Edith, Four Decades of Action for Children; A Short History of the Children’s Bureau, Washington, D.C. : U.S. G.P.O., 1956. Series: Bureau publication (United States. Children’s Bureau), no. 358. Prologue. Full text PDF available at https://www.ssa.gov/history/pdf/child1.pdf Current 9/8/2021

Carson, Mina, Settlement Folk: Social Thought and the American Settlement Movement, 1885-1930, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1990. Carson noted: “The settlers believed [in] … what Florence Kelley called ‘the right to childhood’: provision of the minimal conditions conducive to the child’s healthy development.” p. 110 “In Some Ethical Gains through Legislation (1905), Florence Kelley [said]…: ‘The noblest duty of the Republic is that of self-preservation by so cherishing all its children that they, in turn, may become enlightened self-governing citizens.’” p. 110.

Duffus, R.L., Lillian Wald: Neighbor and Crusader, New York: The Macmillan Company, 1939, p. 87.

Goldmark, Josephine, Impatient Crusader: Florence Kelley’s Life Story, Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1953.

[Kelley] Wischnewetzky, Florence Kelley, Our Toiling Children, Chicago: Women’s Temperance Publication Association, 1889, pp. 3-4, p. 19-21, (quoting Commissioner C.F. Peck, Report of the Bureau of Labor Statistics of New York, 1884, p. 143), 23. Full text available at http://florencekelley.northwestern.edu/archives/kelley/ Current 9/8/2021

Kelley, Florence, Some Ethical Gains Through Legislation, New York: The Macmillan Company, 1905, pp. 3, 6-7 7-8, 24, 48.

Lindenmeyer, Kriste, “A Right to Childhood”: The U.S. Children’s Bureau and Child Welfare, 1912-46, Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1997.

Lindenmeyer writes, “In her 1905 publication, Some Ethical Gains through Legislation, Progressive Era reformer Florence Kelley wrote that ‘a right to childhood…follows from the existence of the Republic and must be guarded in order to guard its life.’” p. [1]

Lubove, Roy, The Progressives and the Slums: Tenement House Reform in New York City, 1890-1917, np: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1962, p. 210.

National Child Labor Committee, Florence Kelley, Secretary. Reports from State and Local Child Labor Committees and Consumers’ Leagues, George Hall, Arthur O. Lovejoy, Henry J. Harris, H. Wirt Steele, Edward W. Frost, Scott Nearing, I. A. Loos, C. B. Wilmer, Benjamin J. Baldwin, Charles L. Cone, A. J. McKelway, Millie R. Trumbull, Phebe T. Sutliff, A. M. Beardsley, Florence L. Sanville, Daniel Miller, Edith M. Howes, Florence G. Taylor, Catharine Avery, Geraldine Gordon, Florence Kelley and Samuel McCune Lindsay, Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science , Vol. 29, Child Labor (Jan., 1907), pp. 142-183. Published by: Sage Publications, Inc. in association with the American Academy of Political and Social Science Article Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1010431 Jan. 1907, pp. 178-179.

Riis, Jacob, The Children of the Poor, New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1908 (c1892), pp. 21, 95, 101, 109-110, 111. Full text available at: https://archive.org/details/childrenofpoor00riisuoft/mode/2up?view=theater (openlibrary.org) Current 9/8/2021

Riis, Jacob A., How the Other Half Lives How the other half lives, studies among the tenements of New York, by Jacob A. Riis, New York: C. Scribner’s Sons, 1890. Full text available at https://www.gutenberg.org/files/45502/45502-h/45502-h.htm Image of “Susie” is at p. 110 Current 12/21/2021.

Stambler, Moses, The Effect of Compulsory Education and Child Labor Laws on High School Attendance in New York City, 1898-1917, Source: History of Education Quarterly, Vol. 8, No. 2 (Summer, 1968), pp. 189-214 Published by: History of Education Society. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/367352

Stambler writes, “The General Secretary of the National Child Labor Committee, Owen R. Lovejoy, noted the extensive lobbying conducted by the Committee and stressed the intimate connection between child labor legislation and compulsory education. In his article appropriately entitled, ‘The Functions of Education in Abolishing Child Labor,’ [1908] he perceived compulsory education as a means to humanitarian ends and a positive way of meeting the pressure of displaced children. Lovejoy realized that, ‘Reforms of the abuses of child labor are accomplished by two methods: compulsion and attraction.’ He stressed the need for both the negative prohibition of child labor legislation plus the ‘positive legislation for compulsory school attendance.’ (24),” pp. 197-198

Trattner, Walter I., Crusade for the Children: A History of the National Child Labor Committee and Child Labor Reform in America, Chicago: Quadrangle Books, 1970, p. 146-7.

Historian Trattner’s research further validates the anecdotes and data of Wald and Kelley. He succinctly and eloquently summarizes their findings in his work on American child labor as follows:

“Child labor in the tenements combined the evils of long hours, low wages, and monotonous work in filthy, badly ventilated, and overcrowded rooms, with the degradation of neglected education and shattered health; few other kinds of labor sapped the strength and spirits of children quite so pervasively.” p. 146.

“Almost any commodity small enough to be carried and not requiring the use of elaborate machinery or highly skilled labor could be manufactured or finished at home. The work varied from pulling bastings—usually the task of the youngest ones—to sewing on buttons, putting linings in coats, making artificial flowers, stringing beads, embroidering lace, or making cigarettes, hair brushes, powder puffs, and other small items.” p. 146.

“Children in households that did home work had little chance of receiving a decent education. Because most of the work could be done by unskilled labor, parents frequently kept their children out of school to help them. Those children who did attend school would work at home before or after classes, often into the early morning hours, making it virtually impossible for them to keep up with their lessons; thus they would fall behind and then drop out. If they were of pre-school age—and studies showed that many were—so much the better, for they could work all day without being bothered about school.” p. 147.

Van Kleeck, Mary, Child Labor in Home Industries Author(s): Mary van Kleeck Source: The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, Mar., 1910, Vol. 35, Supplement. Child Employing Industries (Mar., 1910), pp. 145-149 Published by: Sage Publications, Inc. in association with the American Academy of Political and Social Science Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1011407 pp. 145, 146.

Wald, Lillian D., The House on Henry Street, NY: Henry Holt & Co., 1915, pp. 133, 152-156.

Wald, Lillian D., Windows on Henry Street, Boston: Little Brown, and Company, 1934, pp. 195-196.

Illustrations

Images are from the National Child Labor Committee Collection at the Library of Congress

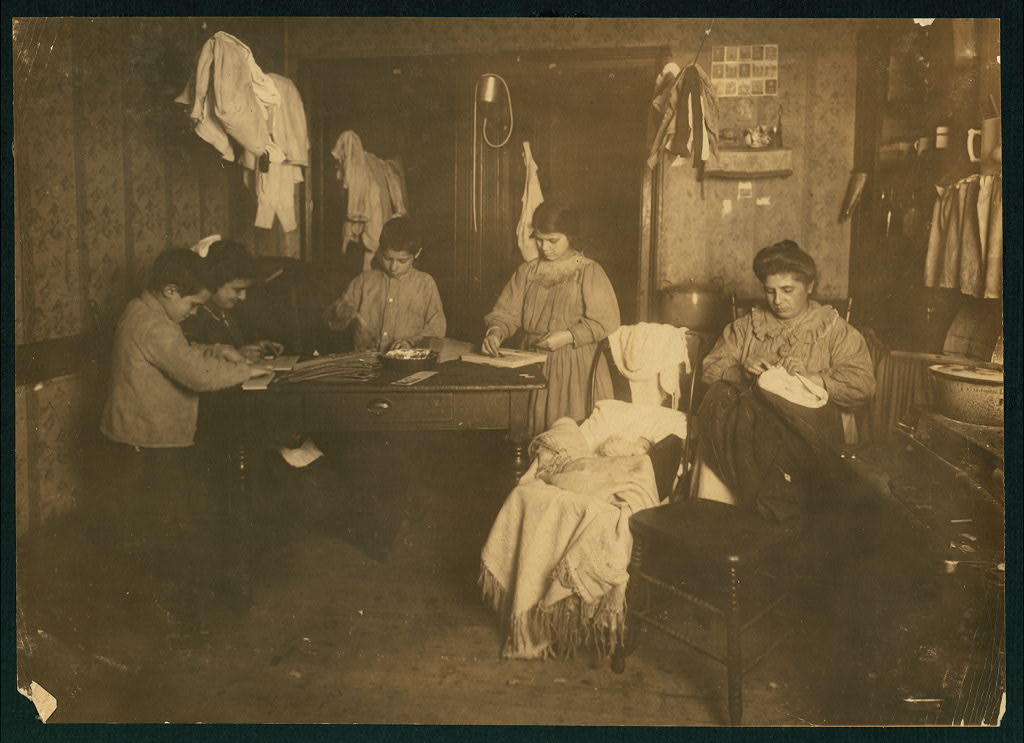

Hine, Lewis Wickes, photographer. [1 P.M. Family of Onofrio Cottone, 7 Extra Pl., N.Y., finishing garments in a terribly run down tenement. The father works on the street. The three oldest children help the mother on garments. Joseph, 14, Andrew, 10, Rosie, 7, and all together they make about $2 a week when work is plenty. There are two babies.Location: New York, New York State]. January, 1913. Image. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/pictures/collection/nclc/item/2018676689/ Current 04/23/2024

Hine, Lewis Wickes, photographer. [Mrs. Tony Racioppo, 260 Elizabeth St., N.Y. 1st floor rear, finishing pants in dirty tenement home. Although it is a licensed house, the whole place is very much run down. The ahllway i.e., hallway is in the same condition as that one at 266 Elizabeth see photo. Baby had bad cough. Mother said recovering from measles.Location: New York, New York State]. February, 1912. Image. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/pictures/collection/nclc/item/2018677014/ Current 12/8/2021

Hine, Lewis Wickes, photographer. 6 P.M. Callabria family, 647 E. 12th St., N.Y. see schedule Mother finishes clothing. The children paste needle packages onto cards and said they all work at times until 10 or 11 P.M. They are 9, 12, 14 and 15 years old and all go to school. They are undersized. The baby in the cart is one month old. Location: New York, New York State. February, 1912. Image. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/pictures/collection/nclc/item/2018677012/ Current 04/22/2024

Hine, Lewis Wickes, photographer. Cutting out embroidery on the dirty kitchen floor. Battista family, 259 E. 151 St. N.Y. On the right is the married daughter, who lives down stairs and usually works there. On her right next to the boy is Flora, said to be 9 years old and very much stunted in size. “Been sick.” Next to her is the mother and next is Linda, 11 years old. The baby, dirty and covered with sores, was being handed about. Probably has impetego. Location: New York, New York State. January, 1912. Image. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/pictures/collection/nclc/item/2018674695/ Current 04/22/2024

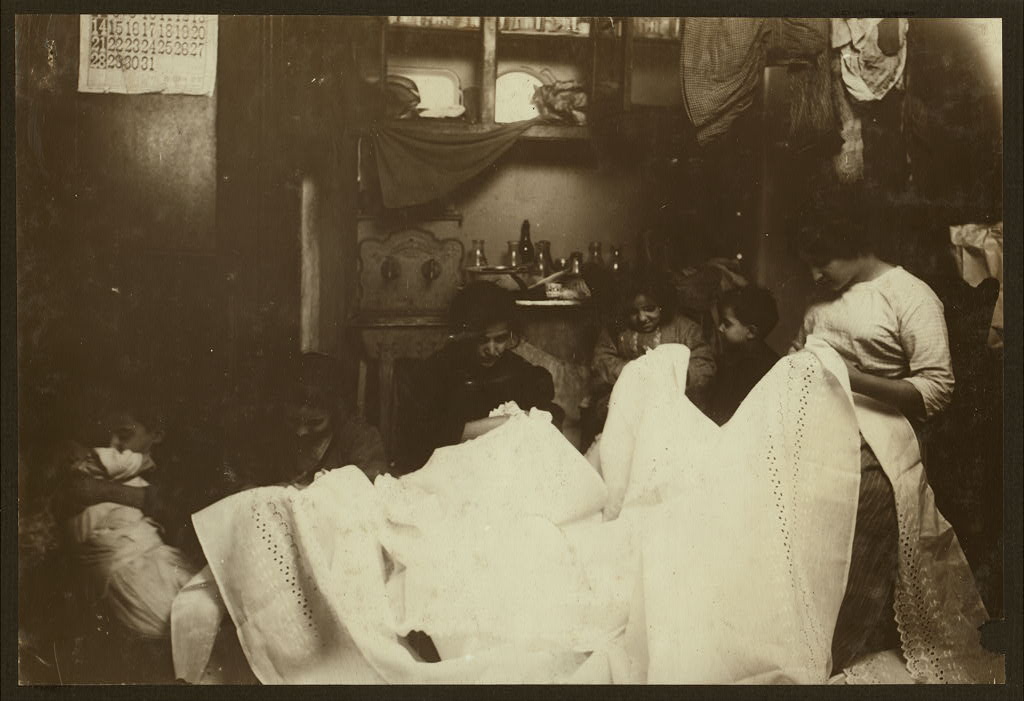

Hine, Lewis Wickes, photographer. [Mrs. Raphael Marengin, … St., first floor rear. Pepine, 10 yrs. old, cracking nuts with her teeth. The mother had just been doing the same. Carmine, 8 years old, has cross eyes, and with the boy about same age works too. Some of them work until 8 or 9 p.m. at times. Boy holding baby is foolish. Husband works on railroad part of the time. 10-year-old-girl cracking nuts with her teeth. The mother had just been doing the same. 8-year-old child has cross eyes and works, as well as the boy. New York City, 1911. Manufacture of food in tenement homes is now prohibited in New York State. Location: New York, New York State]. December, 1911. Image. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/pictures/collection/nclc/item/2018676884/ Current 04/22/2024

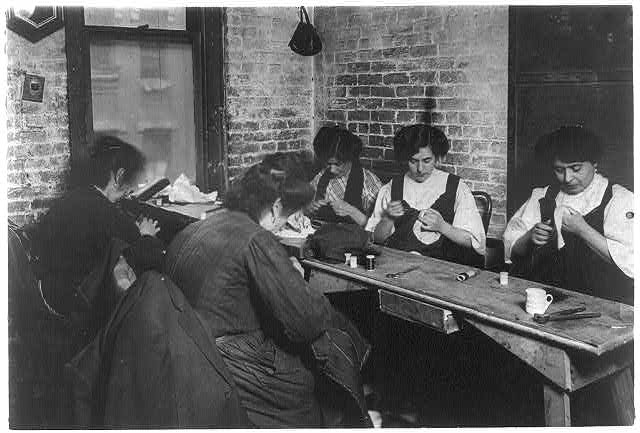

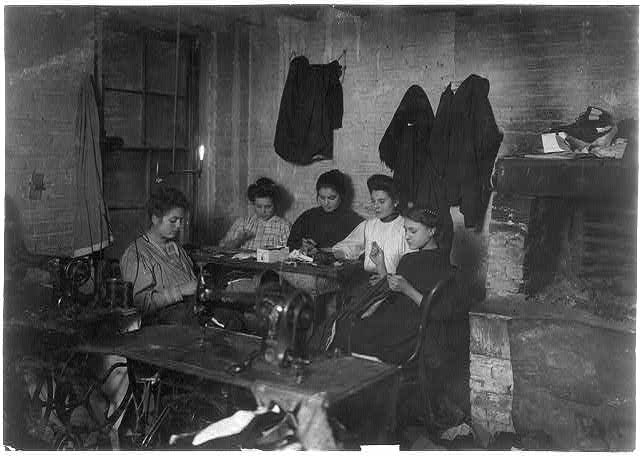

Hines, Lewis Wickes, Title: Group of sweatshop workers in shop of M. Silverman. 30 Suffolk St., N.Y. Feb. 21, 1908. Location: New York, New York (State) Creator(s): Hine, Lewis Wickes, 1874-1940, photographer Date Created/Published: 1908 February 21.

Medium: 1 photographic print. Reproduction Number: LC-DIG-nclc-04454 (color digital file from b&w original print) Rights Advisory: No known restrictions on publication. For information see: “National Child Labor Committee (Lewis Hine photographs),”(https://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/res.097.hine ) Access Advisory: For reference access, please use the digital item to preserve the fragile original item.

Call Number: LOT 7483, v. 1, no. 0027-A [P&P] Repository: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA https://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/pp.print

Link to photo: https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2018673656/ Current 04/22/2024

Hines, Lewis Wickes, Title: Sweatshop of Mr. Goldstein 30 Suffolk St. Witness Mrs. L. Hosford. Location: New York, New York (State) Creator(s): Hine, Lewis Wickes, 1874-1940, photographer. Date Created/Published: 1908 February. Medium: 1 photographic print. Reproduction Number: LC-DIG-nclc-04455 (color digital file from b&w original print) LC-USZ62-51765 (b&w film copy negative). Rights Advisory: No known restrictions on publication. For information see: “National Child Labor Committee (Lewis Hine photographs),”(https://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/res.097.hine ) Access Advisory: For reference access, please use the digital item to preserve the fragile original item.

Call Number: LOT 7483, v. 1, no. 0028-A [P&P] Repository: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA https://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/pp.print Link to photo: https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2018673658/ Current 04/22/2024

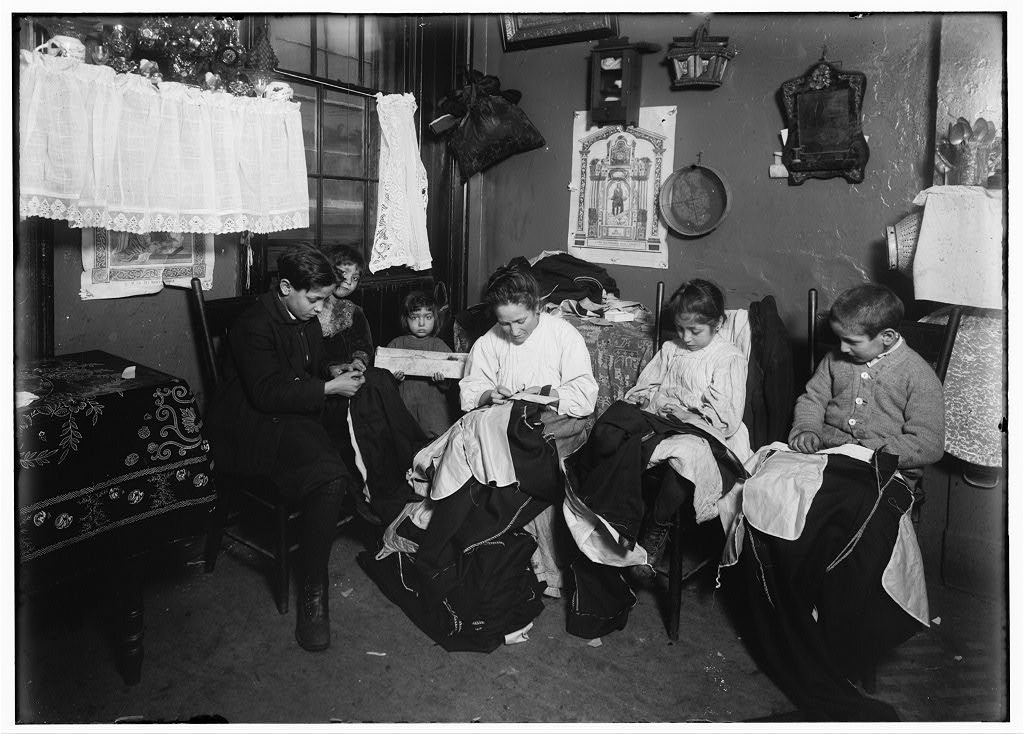

Hines, Lewis Wickes, Title: Group in Sweatshop. Mr. Schneider, 87 Ridge Street Shop located in the second inner court. Group just finishing week’s work. Witness Mrs. Lillian Hosford. Location: New York, New York (State) / Photo 4 P.M. February 21[?], 1908. By Lewis W Hine. Creator(s): Hine, Lewis Wickes, 1874-1940, photographer

Date Created/Published: 1908 February 21. Medium: 1 photographic print.

Reproduction Number: LC-DIG-nclc-04456 (color digital file from b&w original print) LC-USZ62-19966 (b&w film copy negative) Rights Advisory: No known restrictions on publication. For information see: “National Child Labor Committee (Lewis Hine photographs),”(https://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/res.097.hine ) Access Advisory: For reference access, please use the digital item to preserve the fragile original item.

Call Number: LOT 7483, v. 1, no. 0030-A [P&P] Repository: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA https://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/pp.print Link to photo: https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2018673661/ Current 04/22/2024

Hines, Lewis Wickes, Title: Group of women in sweatshop of Mr. Sentrei, 87 Ridge Street, second inner court. Small girl is Mamie Gerhino, 202 Elizabeth Street. She might have been 14 years old. Photo 5 P.M., February 21, 1908. Witness Mrs. Lillian Hosford. Location: New York, New York (State) / by Lewis W. Hine. Creator(s): Hine, Lewis Wickes, 1874-1940, photographer. Date Created/Published: 1908 February 21.

Medium: 1 photographic print. Reproduction Number: LC-DIG-nclc-04457 (color digital file from b&w original print) LC-USZ62-55967 (b&w film copy negative). Rights Advisory: No known restrictions on publication. For information see: “National Child Labor Committee (Lewis Hine photographs),”(https://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/res.097.hine )

Access Advisory: For reference access, please use the digital item to preserve the fragile original item. Call Number: LOT 7483, v. 1, no. 0031-A [P&P]. Repository: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA https://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/pp.print Link to photo: https://www.loc.gov/pictures/resource/cph.3b03845/ Current 04/22/2024

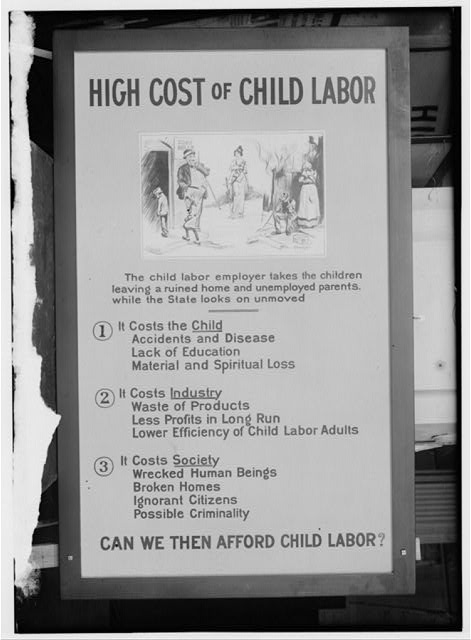

Hine, Lewis Wickes, Title: Exhibit panel. Creator(s): Hine, Lewis Wickes, 1874-1940, photographer. Date Created/Published: [1913 or 1914?]. Medium: 1 photographic print.

1 negative : glass ; 5 x 7 in. Reproduction Number: LC-DIG-nclc-04927 (color digital file from b&w original print) LC-DIG-nclc-05552 (b&w digital file from original glass negative). Rights Advisory: No known restrictions on publication. For information see: “National Child Labor Committee (Lewis Hine photographs),” (https://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/res.097.hine ) Access Advisory: For reference access, please use the digital item to preserve the fragile original item. Call Number: LOT 7483, v. 2, no. 3746 [P&P] LC-H5- 3746. Repository: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA https://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/pp.print https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2018676382/ Current 04/22/2024

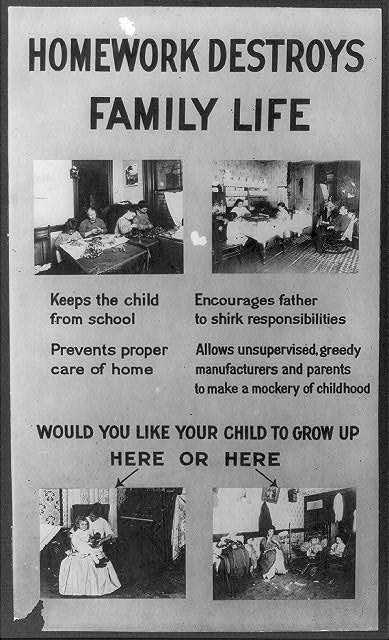

Hine, Lewis Wickes, Title: Exhibit panel. Creator(s): Hine, Lewis Wickes, 1874-1940, photographer. Date Created/Published: [1913 or 1914?]. Medium: 1 photographic print.

1 negative : glass ; 5 x 7 in. Reproduction Number: LC-DIG-nclc-04313 (color digital file from b&w original print) LC-DIG-nclc-04931 (color digital file from b&w original print) LC-DIG-nclc-05554 (b&w digital file from original glass negative) LC-USZ62-46384 (b&w film copy negative). Rights Advisory: No known restrictions on publication. For information see: “National Child Labor Committee (Lewis Hine photographs),” (https://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/res.097.hine ) Access Advisory: For reference access, please use the digital item to preserve the fragile original item. Call Number: LOT 7481, no. 3750 [P&P] LOT 7483, v. 2, no. 3750 LC-H5- 3750 Repository: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA https://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/pp.print Link to photo: https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2018676386/ Current 4/22/2004

Hine, Lewis Wickes, Title: [Taking bags home to be mended. 5 to 11 years old. Market.] Location: [Boston, Massachusetts]. / [Lewis W. Hine] Creator(s): Hine, Lewis Wickes, 1874-1940, photographer. Date Created/Published: [1917 January 27]. Medium: 1 photographic print. Reproduction Number: LC-DIG-nclc-05155 (color digital file from b&w original print). Rights Advisory: No known restrictions on publication. For information see: “National Child Labor Committee (Lewis Hine photographs),” (https://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/res.097.hine ) Access Advisory: For reference access, please use the digital item to preserve the fragile original item. Call Number: LOT 7483, v. 2, no. 4683-A [P&P]. Repository: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA https://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/pp.print Link to photo: https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2018677483/ Current 04/22/2024

Hine, Lewis Wickes, Title: Taking bags home to be mended. 5 to 11 years old. Market. Location: Boston, Massachusetts / Lewis W. Hine. Creator(s): Hine, Lewis Wickes, 1874-1940, photographer. Date Created/Published: 1917 January 27. Medium: 1 photographic print. Reproduction Number: LC-DIG-nclc-05154 (color digital file from b&w original print). Rights Advisory: No known restrictions on publication. For information see: “National Child Labor Committee (Lewis Hine photographs),” (https://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/res.097.hine ) Access Advisory: For reference access, please use the digital item to preserve the fragile original item. Call Number: LOT 7483, v. 2, no. 4683 [P&P]. Repository: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA https://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/pp.print Link to photo: https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2018677482/ Current 04/22/2024

Copyright Anne M. Filiaci 2024