By Anne M. Filiaci, Ph.D.

Mabel Hyde Kittredge joined the Henry Street family around the turn of the twentieth century. She soon became one of Wald’s close friends and confidantes. As a non-nurse resident, Kittredge initially engaged in the Settlement’s club work, but before long she found that her true calling was organizing “domestic science” (or “practical housekeeping”) classes for young, single working women who lived in the neighborhood’s tenements.

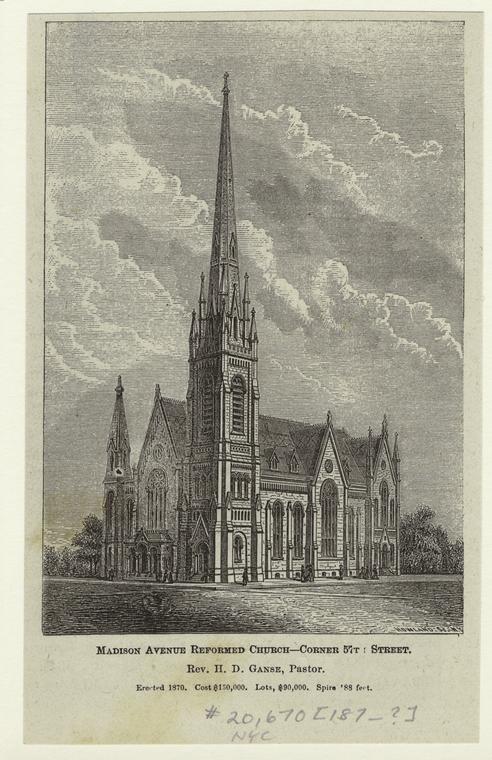

Kittredge was one of Wald’s “uptown” friends and supporters. She had a reputation as a “Park Avenue socialite who frequently played bridge whist all night after she had played in a golf tournament all day.” Born the same year as Wald (1867), Kittredge was one of three daughters of the Rev. Dr. Abbott Eliot Kittredge. Her father was a graduate of the Roxbury Latin School (MA), Williams College, and the Andover Theological Seminary. In the fall of 1886, he became pastor of the Madison Avenue Reformed Church, located on Madison Avenue and Fifty-Seventh Street in New York City. He also served as President of the General Synod of the Reformed Church in America.

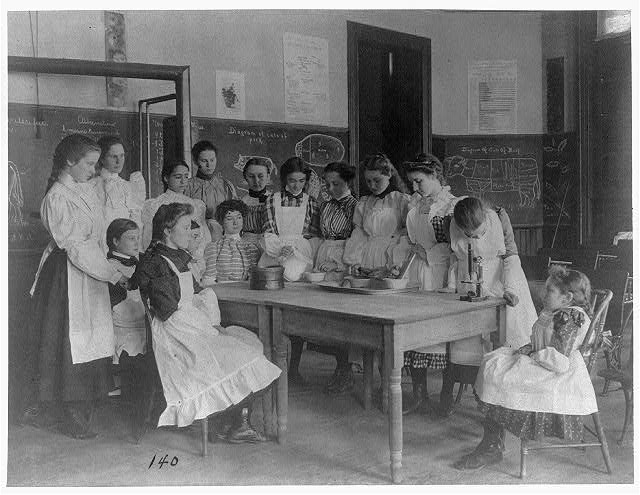

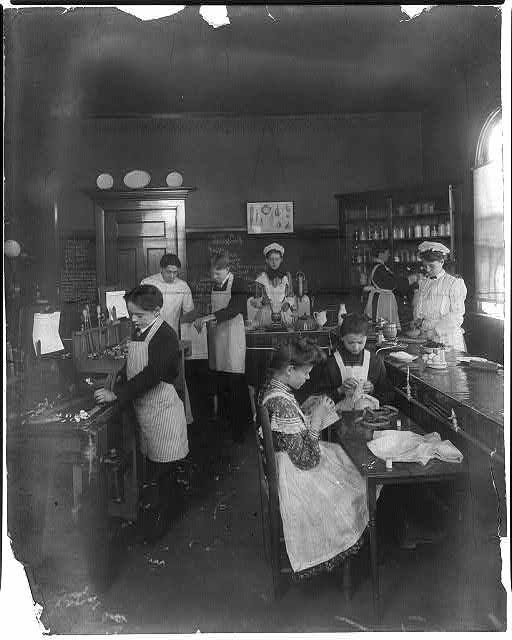

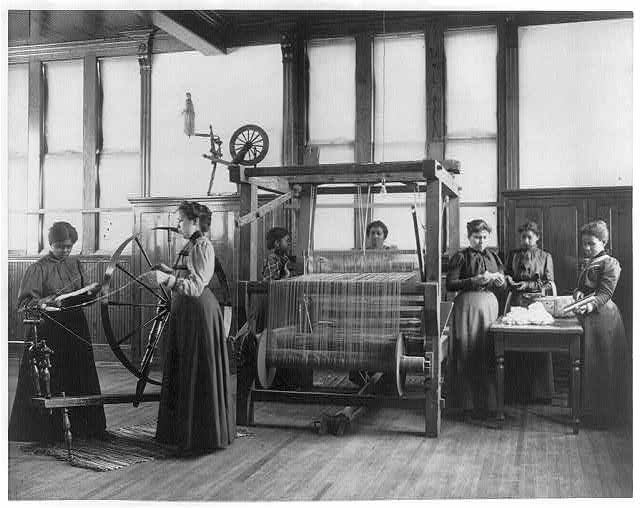

Soon after he arrived in New York, Reverend Kittredge founded and became President of the Manhattan Working Girls Society (MWGS). Organized on July 15, 1887, the purpose of this Society was to “afford refining influence to…working girls” by offering classes in “such subjects as cooking, dressmaking, calisthenics, and singing.”

In at least some of its functions, the MWGS bore a resemblance to the vocation of domestic training later chosen by Rev. Kittredge’s daughter Mabel. The younger Kittredge’s work, however, was different from that of her father in two crucial ways. She was running a secular enterprise that was not connected in any way with a church or religion. Also unlike her father, she promoted her work as an educational and skill-building opportunity rather than a vehicle for moral and social improvement. In fact, Mabel Kittredge went out of her way to avoid any appearance of class or ethnic condescension. She was adamant that

the average tenement housewife is a remarkably good housekeeper, and that for the association to attempt to teach her what might be called the rudiments of the tenement kitchen would be both presumptuous and a waste of time.

Rather than presuming to merely instruct young women, she said, the “teachers employed by the association… [while] trained…in domestic science,” sought to combine their theoretical knowledge “with the practical experience of those dwellers in tenement houses with whom they come in contact.” By taking this approach, Kittredge asserted, there was “something of value…gained on both sides.”

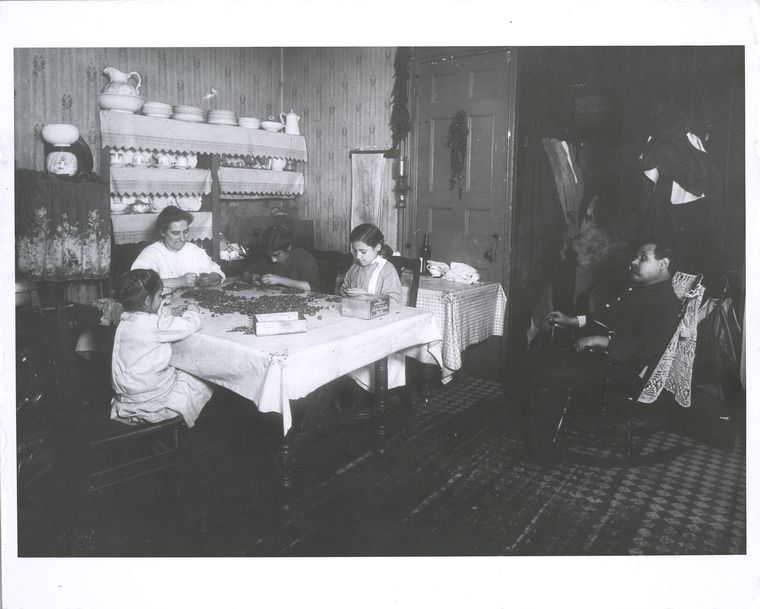

Lillian Wald encouraged and supported Kittredge’s work—which was initially sponsored by the Henry Street Settlement—because it was a good fit with Wald’s specific public health goals. Wald had, after all, been fighting to improve her patients’ living conditions since she moved to the Lower East Side in 1893. She later provided the example of one patient, “Annie F,” whom she encountered in an upper flat of a Monroe Street tenement, “lying on a tumbled bed, rigid in the braces which encased her from head to feet.” Annie’s home also served as a sweatshop, and “All about her white goods were being manufactured.” Realizing that the girl’s well-being depended on more than nursing care, Wald tried her best to transform the sick girl’s environment—“A sweatshop was transfigured for Annie,” she wrote, “when we put pretty white curtains at the window upon which she gazed, hung up a bird-cage, and placed a window-box full of growing plants for her to look at during the long days.”

Throughout the 1890s, Wald also testified before and worked with New York City’s Tenement House Commissions and Committees, which sought to clean up the streets and to ensure that the city’s poor lived in buildings that were clean and safe. Wald’s early letters to her benefactors are replete with instances that make it clear that she saw creating a hygienic environment as an integral part of her work. On August 29, 1893, she wrote,

Mrs. Silverstein, to whom you sent money is still living and… one of the nurses goes daily, buys food, washes her and the children and occasionally also we pay a woman to scrub the place and clean up more thoroughly….

By March of 1894, the Ethical Culture Society was providing Wald with a source of income that she used for cleaning the apartments of patients:

The money allowed by the Women’s Conference of the Ethical Society has been increased to $20 a week and that money is all spent, employing women to clean the rooms of the tenements where illness takes us.

When she attempted to clean and beautify her patients’ tenement homes, Wald was often stymied by the presence of sweatshops. This widespread use of the home as a workplace created a crowded and unsanitary environment, and also interfered with the benefits that accrued from a private, structured family life. She had observed that children who lived in tenements often grew up without the benefit of the family dinner, a daily ritual where the whole family sat down together, where children could inform their parents of their struggles and triumphs and parents could pass on their knowledge of traditions, culture, current events and manners to their children. This, she argued, greatly reduced the chances that poor children had to take advantage of America’s promise of upward mobility. “[C]hildren in normal [sic] homes,” she wrote, “get education apart from formal lessons and instruction. Sitting down to a table at definite hours, to eat food properly served, is training, and so is the orderly organization of the home….” She asked Americans to compare a “regulated domestic life with the experience of children…who may never have been seated around a table in an orderly manner, at a given time, for a family meal,” “[w]here the family is large and the rooms small, and those employed return at irregular hours, its members…fed at different times…”

Wald believed that Kittredge’s efforts to train young women in “domestic science” would serve to create cleaner, more pleasing and attractive homes, and also to promulgate traditions (such as the family dinner) that she asserted would give tenement children a greater chance for success. While the city’s public schools offered some instruction in “domestic science” subjects, neither Wald nor Kittredge found the curriculum comprehensive or satisfactory. Wald, with her usual tact and diplomacy, granted that “instruction” offered in the schools “is of great value to those admitted to the classes.” However, she expressed regret in the lack of “sufficient” funds “to meet all the requirements.” She also pointed out that by the time the subjects were taught, many young teenage women had already quit school and “gone to work.” These girls, Wald said, “will perhaps never again have the leisure or inclination to prepare meals for husband and children….”

Wald and Kittredge, along with other leading domestic science educators, also found fault with the purely theoretical approach to housekeeping being taught in schools. “[T]he…method employed in the schools,” Wald wrote, “never seemed to us sufficiently related to the home conditions of vast numbers of the city’s population….” Kittredge was more specific (and blunt)—“New York’s public schools, of course, teach domestic science—out of a book,” she said.

In an attempt to respond to these challenges, Kittredge implemented the “experiment of housekeeping centers.” The program was one that Wald was years later proud to proclaim had begun at the Henry Street Settlement. These centers taught young neighborhood women cooking, housekeeping, decorating, budgeting, and other domestic skills.

At first, Wald said, “when the settlement undertook the teaching of domestic science,” teachers used the Settlement’s own “stove, refrigerator, bedrooms, and so on….” But they soon found that “neither … single bedrooms” nor “rooms set apart for distinct purposes” were “entirely satisfactory in teaching domestic procedure to the average neighbor.” Kittredge eventually purchased or rented actual tenement house flats that she used as model “Practical Housekeeping Centers”—a concept that evolved under her guidance through trial and error over time.

In November of 1901, while still living at the Settlement, Mabel Hyde Kittredge rented a four-room “model flat” in a “typical Henry Street tenement” at 226 Henry Street. Kittredge left the flat empty of the “stage properties which had characterized early [model] kitchens and bedrooms.” Instead, she provided “a series of talks on furnishing.” At the end of these, the class itself furnished the flat. The teacher made sure that this was done “inexpensively and with furniture that required the least possible labor to keep it free from dirt and vermin.”

With cleanliness and efficiency in mind, teachers discouraged rugs and hangings as dust- and dirt-catchers, showed people how to use front rooms as bedrooms, encouraged bare and open spaces, and demonstrated the use of space-saving furniture like trundle beds. Those who taught the classes “used nothing which the people themselves could not procure—a tiny bathroom, a gas stove, no ‘model tubs,’ but such as the landlord provided for washing.” Once the flat was furnished, the center offered classes in “[c]ooking, preservation of food, care of beds, ventilation, cleaning, and all the round of household duties…taught under actual conditions of life.”

Perhaps because of her desire to avoid appearing “condescending,” Kittredge did not target “the average tenement housewife,” but instead sought and attracted young single working girls of marriageable age. Wald declared, “[t]he first winter that the center was opened the entire membership of a class consisted of girls engaged to be married—clerks, stenographers, teachers; none were prepared and all were eager to have the homes which they were about to establish better organized and more intelligently conducted….” Kittredge also attracted young women who looked forward to marriage but were not yet engaged—“When one young woman announced her betrothal, she added, ‘And I am fully prepared because I have been through the Housekeeping Center.’”

Kittredge’s work had started—but it was far from finished. She would soon leave Henry Street Settlement to make her own mark in the nascent field of domestic science. But she and Wald would continue to act as allies throughout their careers.

Bibliography

American Journal of Nursing, “Editor’s Miscellany,” The American Journal of Nursing, Vol. 2, No. 12 (Sep., 1902), pp. 1042-1043.

Carson, Mina, Settlement Folk: Social Thought and the American Settlement Movement, 1885-1930, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1990, pp. 92-93

“Christmas For Working Girls: Entertainment by Their Society at Bethany Chapel—Addresses by Miss Kyle and Chauncey M. Depew,” New York Times, January 10, 1896.

Davis, Allen F., Spearheads for Reform: The Social Settlements and the Progressive Movement, 1890-1914, New York, Oxford University Press, 1967, p. 46.

Duffus, R.L., Lillian Wald: Neighbor and Crusader, New York: The Macmillan Company, 1939, quoting Wald, pp. 115-116.

Dynes, Wayne R. and Stephen Donaldson, eds., Homosexuality and Government, Politics, and Prisons, (Studies in Homosexuality, v. X), NY: Garland Publishing, Inc., 1992, p. 42-43.

Kittredge, Mabel Hyde, Papers, birth date, WorldCat subject entry, Born in 1867 (d. 1955) Link to Site Current 2/15/18.

“Rev. Dr. A.E. Kittredge Dies; Pastor Emeritus of Madison Avenue Reformed Church Was 78,” New York Times, December 18, 1912.

Schrom Dye, Nancy, As Equals and As Sisters: Feminism, the Labor Movement, and the Women’s Trade Union League of New York, Columbia, Univ. of Missouri Press, 1980, p. 10.

“Teaching the Wives and Mothers of the Future: Unique Experiment in Four City ‘Housekeeping Centres.’” New York Times, Feb. 6, 1910.

Wald, Lillian D., The House on Henry Street, N:Y: Henry Holt & Co., 1915, pp. 107-111, p. 115.

Wald, Lillian D., Lillian Wald Papers. New York: New York Public Library, 1983, Ltr. to Jacob H. Schiff, 59 Cedar St., from LDW, 95 Rivington St., Aug. 29, 1893. LDW to Hon. Jacob H. Schiff and Mrs. Solomon Loeb, from LDW, 27 Jefferson Street, March 4, 1894.

Woods, Robert A. & Albert J. Kennedy, Handbook of Settlements (Russell Sage Foundation), NY: Charities Publication Committee, 1911, pp. 191-192

Woods, Robert A. and Albert J. Kennedy, The Settlement Horizon: A National Estimate, New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 1922, p. 143.

Illustrations

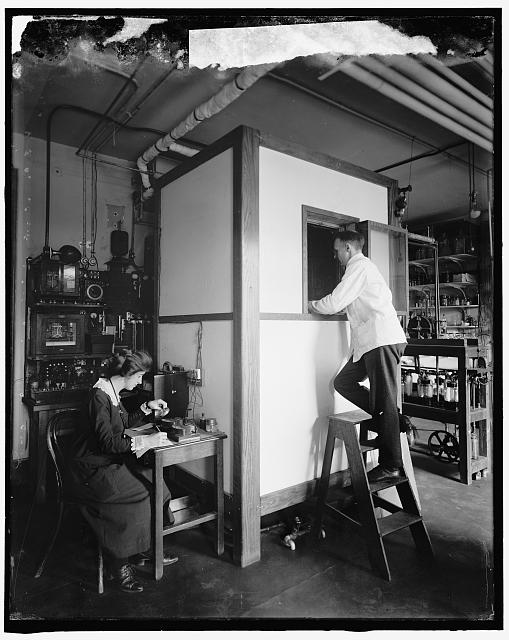

Baker & Cornwall, photo, “A modern manual training school,” 1905 LOC Prints & photos, Link to Illustration Current 10//15/18

Harris & Ewing, photographer, “Home Economics Section,” [between 1910-1920]. LOC Prints & Photos Link to Illustration Current 10//15/18

Harris & Ewing, photographer, “Home Economics Section,” [between 1910-1920]. LOC Prints & Photos Link to Illustration Current 10//15/18

Housekeeping Notes Paperback – February 28, 2010, by Mabel Hyde Kittredge (Author) Link Current 10//15/18

Housekeeping Notes Paperback – February 28, 2010, by Mabel Hyde Kittredge (Author) Link Current 10/15/18

Johnston, Frances Benjamin, “African-American women weaving rug in home economics class at Hampton Institute, Hampton, VA,” 1899 or 1900, LOC Prints and Photographs, Link to Illustration Current 10/15/18

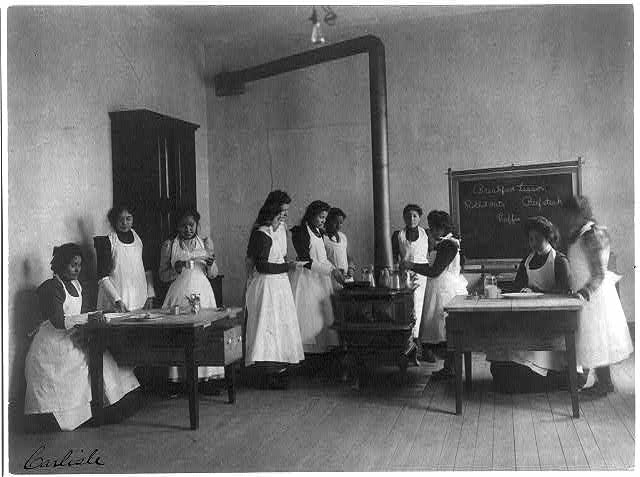

Johnston, Frances Benjamin, “[Breakfast lesson in home economics class for women, Carlisle Indian School, Pa.]”, 1901, LOC Prints and Photographs, Link to Illustration Current 10/15/18

Johnston, Frances Benjamin, “[Girls posed in home economics class, 1st Division, Washington, D.C.]” Washington, DC, 1899? LOC Prints and Photographs, Link to Illustration Current 10/15/18

Johnston, Frances Benjamin, “Home Economics Class,” (1899?), Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Link to Illustration Current 3/14/18

Johnston, Frances Benjamin, “[Home Economics Class,” 2nd Division]” Washington, DC, 1899? LOC Prints and Photographs, Frances Benjamin Johnston Collection, Link to Illustration Current 10/15/18

Mabel Hyde Kittredge, from a 1917 publication. 1 January 1917 “You Might Do This In Your City” The Woman Citizen (September 15, 1917): 294. No photographer named in original source. Wikipedia Commons, Link to Illustration Current 10//15/18.

Madison Avenue Reformed Church, corner of 57th Street, New York Art and Picture Collection, The New York Public Library. “Madison Avenue Reformed Church — corner 57th Street” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 187?-. Link to Illustration Current 10//15/18.

The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Photography Collection, The New York Public Library. “Doing piece work at home making artificial flowers” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1900 – 1937. Link to Illustration Current 10//26/18

The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Photography Collection, The New York Public Library. “Doing piece work at home while father watches, New York tenement” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1900 – 1937. Link to Illustration Current 10//26/18

The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Photography Collection, The New York Public Library. “Making artificial flowers” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1900 – 1937. Link to Illustration Current 10//15/18

The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Photography Collection, The New York Public Library. “Mrs. Rena shelling nuts with a neighbor” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1900 – 1937. Link to Illustration Current 10/15/18

The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Photography Collection, The New York Public Library. “Sewing work at home” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1900 – 1937. Link to Illustration Current 10/15/18

The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Photography Collection, The New York Public Library. “Shelling nuts at home” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1900 – 1937. Link to Illustration Current 10/15/18

The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Photography Collection, The New York Public Library. “Shelling pecans at home” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1900 – 1937. Link to Illustration Current 10/15/18

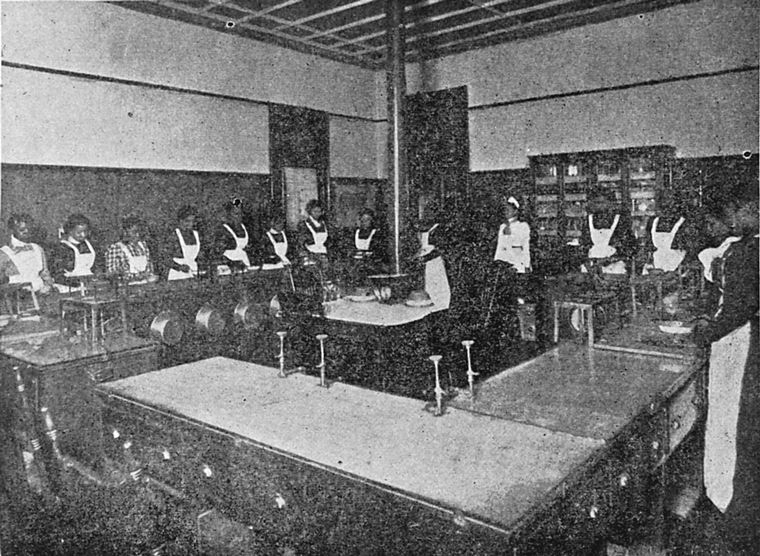

Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Jean Blackwell Hutson Research and Reference Division, The New York Public Library. “Class in Domestic Science, Summer High School, St. Louis, Missouri.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1902. Link to Illustration Current 10/15/18

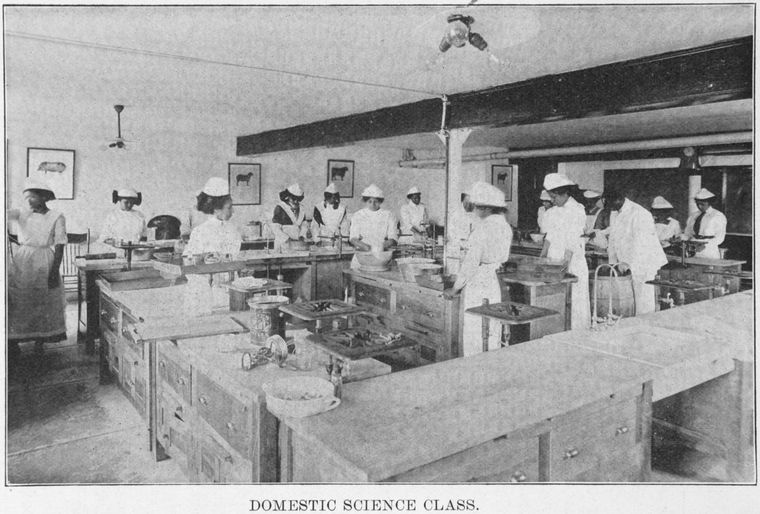

Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Manuscripts, Archives and Rare Books Division, The New York Public Library. “Domestic Science class.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1915. Link to Illustration Current 10/15/18

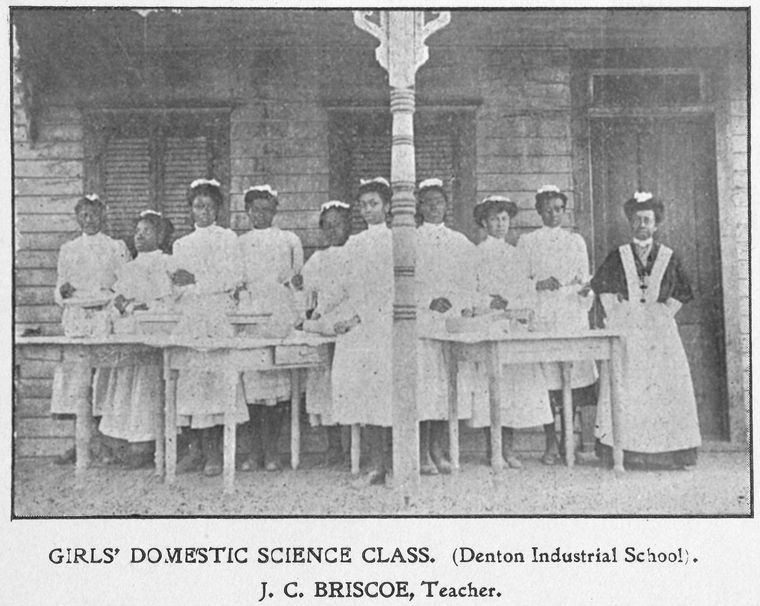

Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Jean Blackwell Hutson Research and Reference Division, The New York Public Library. “Girls’ Domestic Science Class; [Denton Industrial School]; J. C. Briscoe, teacher.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1907-. Link to Illustration Current 10/15/18

“YWCA Domestic Science Class,” Boston Young Women’s Christian Association, American Kitchen Magazine, Nov. 1902, Wikimedia Commons Link to Illustration Current 10/14/18

Copyright Anne M. Filiaci 2018