By Anne M. Filiaci, Ph.D.

Declaration of Dependence by the Children of America in Mines and Factories and Workshops Assembled / Whereas, We, Children of America, are declared to have been born free and equal, and / Whereas, We are yet in bondage in this land of the free; are forced to toil the long day or the long night, with no control over the conditions of labor, as to health or safety or hours or wages, and with no right to the rewards of our service, therefor be it / Resolved, I— That childhood is endowed with certain inherent and inalienable rights, among which are freedom from toil for daily bread; the right to play and to dream; the right to the normal sleep of the night season; the right to an education, that we may have equality of opportunity for developing all that there is in us of mind and heart. / Resolved, II— That we declare ourselves to be helpless and dependent; that we are and of right ought to be dependent, and that we hereby present the appeal of our helplessness that we may be protected in the enjoyment of the rights of childhood. / Resolved, III— That we demand the restoration of our rights by the abolition of child labor in America. – Alexander J. McKelway, 1913

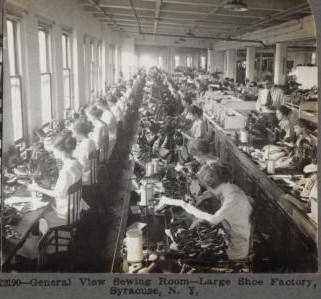

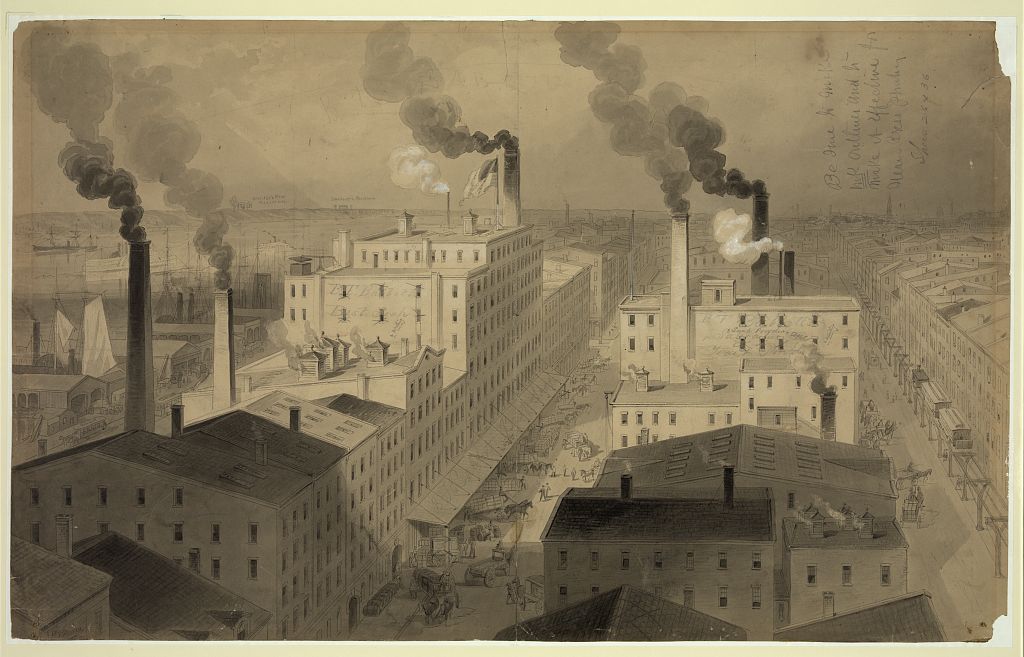

In second half of the nineteenth century, American factories could be found anywhere from large cities to small villages. They occupied sprawling complexes, single buildings, or large open rooms in warehouses. One thing that they did share in common was that virtually all employed children.

Boys and girls had worked throughout history—their labor was essential in the home, on farms and as apprentices or clerks in shops. But while most types of child labor remained widely acceptable among Americans, many viewed the presence of children in factories with suspicion. Unlike their labor in more traditional work settings, factories did not provide close adult supervision and mentoring. And while traditional workplaces could be defended as bolstering morality and providing education, skills and training, factories explicitly focused only on production, speed and profit.

" order_by="sortorder" order_direction="ASC" returns="included" maximum_entity_count="500"]Reformers gave voice to the public fear that children in factories were not being adequately supervised, mentored or educated. They argued that when young people who worked in factories remained uneducated and did not learn valuable skills or develop a strong work ethic, as adults they would lack the tools universally viewed as necessary for the development of productive and informed citizens in a relatively new republic.

Florence Kelley, who would spend decades fighting for the rights of women and children workers, was one of America’s most effective advocates for ending the practice of child labor. Her 1889 expose, Our Toiling Children, provided overwhelming evidence that factories throughout the country employed not just youth, but very young children. “In New Jersey,” she wrote, “previous to the appointment of factory inspectors in 1883, the labor power of children seven and eight years old, was a commodity extensively consumed in the mills of that state.” (Kelley, Our Toiling Children, p. 4)

“In Wisconsin,” she continued, “thirteen knitting mills employ 1,583 persons. The work is performed mostly by boys and girls.” (Kelley, Our Toiling Children, pp. 5-6) The 1875 state census in Rhode Island, Kelley reported, revealed that among those who worked for wages, 146 were nine-years old, 64 were eight, eight were seven, five were six, and “three but five years old.” (Kelley’s emphasis) (Kelley, Our Toiling Children, p. 4)

Kelley found that even in the year 1888—one year before she published Our Toiling Children—the Commissioner of Ohio’s Bureau of Labor Statistics discovered girls “‘in the factories and in the planing mills running planers, and in the potteries doing men’s work.’” At the same time, fifty Columbus establishments making cigars and “stogies” employed 1,000 people, of whom fewer than 100 were adult males. The Commissioner found a large number of children workers in “the industrial establishments’” of Ironton as well. There, at least 300 of the 1,500 workers were young boys. (Kelley, Our Toiling Children, p. 5)

Late nineteenth-century American children worked in the glass industry, in “electric light works, …silk, cotton, and woolen mills, rubber works, scissors, shoe, bag, and box making, in the potteries…in needle and lamp making, in the manufacture of medicinal plasters, wall papers, snuff, crackers, button-holes, cigars, shirts, organs, saws and baskets….” (Kelley, Our Toiling Children, pp. 6-7)

“[I]n short,” Kelley concluded, children worked “in every branch in which the application of machinery” made their labor feasible. (Kelley, Our Toiling Children, pp. 6-7)

Kelley also spoke to the conditions under which these children worked, emphasizing the health and safety risks they encountered on a daily basis with chilling detail—

The conditions under which little children work are fraught with danger to life and limb, to health, morals and intelligence. The danger to life takes the form of fire, boiler explosions, unguarded machinery, uncovered vats, and tanks of boiling fluids, fatal illnesses from contagion, foul air and poisonous work. (Kelley, Our Toiling Children, p. 7)

Youngsters, she revealed, “employed in vast numbers in mills of many kinds” tended “steam-driven machinery” that left them “especially exposed to danger of explosion.” (Kelley, Our Toiling Children, p. 10) Death by fire was another risk, with horrific consequences to children. “In the Granite Mill disaster in Massachusetts in 1874,” Kelley writes, “a number of children under ten years of age were burned to death.” (Kelley, Our Toiling Children, p. 4)

In the days before government regulated workplace safety, children in factories also died by “drowning or scalding in vats and tanks of liquids,” from “being torn limb from limb by revolving shafting,” and by “cleaning machinery while in motion.” (Kelley, Our Toiling Children, p. 17-18) Kelley provided vivid, horrific, real-life details on these types of deaths. She spoke of

death by drowning or scalding in vats and tanks of liquids used in industrial processes. Take, as an illustration, the case of Albert Marsh, aged twelve years, who was drowned in September, 1888, in a Newark (N.J.) rubber works by falling into a naphtha tank. (Kelley, Our Toiling Children, p. 17)

She graphically described scalping and dismemberment—other “especially horrible” deaths that occurred with some frequency, especially to girls and women–

being torn limb from limb by revolving shafting…. menaces girls more often than boys, because skirts and hair braids are particularly liable to be caught. The New York factor[y] inspectors mention a large number of terrible ‘accidents’ of this kind to women and girls. The ‘accidents’ caused by cleaning machinery while in motion are simply countless.” (Kelley, Our Toiling Children, p. 17)

Kelley estimated that about “‘one-third of the accidents” were “‘caused by’” refusing to slow down production and “‘cleaning the machinery while in motion.’” (Kelley, Our Toiling Children, pp. 17-18) She pointed out that these accidents could be prevented by the simple act of shutting down the machines when they needed to be cleaned, fixed or adjusted, and asserted that the only reason for keeping the machinery running was to increase profits. As proof, she quoted Inspector Fell of New Jersey:

‘It is too much the practice of management of factories, for the purpose of saving five minutes of time, rather than stop the machinery, to allow (if they do not command) boys as well as men to replace a belt which has slipped off a pulley, while the driving shaft giving the power to the pulley, is running at full speed; or oftener, to shut down to half-speed which is a dangerous practice and should receive the fullest condemnation.’ (Kelley, Our Toiling Children, pp. 17-18)

According to Fell, factory management and owners also failed to prevent accidents because they refused to invest in safety features that would protect children from hazardous equipment—

‘The number of accidents occurring daily through unprotected machinery is really frightful. It is estimated that from fifty to sixty persons are killed or injured daily through accidents occurring by operating buzz saws. We frequently read of young girls having their scalps torn off, boys having their fingers and arms cut off, or injured; death by being carried around shafting and so on….’ (Kelley, Our Toiling Children, pp. 17-18)

Other children who worked in factories risked their long-term health if not their lives. Kelley reported on poorly-paid flower makers who suffered frequent headaches as a result of breathing the fumes from dyes day after day. An “artificial flower-maker” who “testified before the New York Bureau of Statistics of Labor” revealed

I work where twenty-one girls are employed in a little room. I know many girls working who are under fourteen years of age; we work nine hours a day and I earn $1.50 (one dollar and fifty cents) a week. The girls often have to go home with headaches especially when we work on carmine or yellow.” (New York Bureau of Statistics of Labor Report for 1884, p. 181, quoted in Kelley, Our Toiling Children, p. 24)

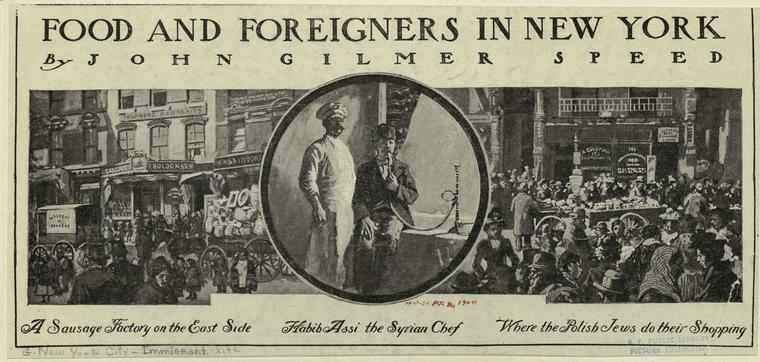

Children who worked in bakeries suffered from smoke inhalation, as reported by a cigar maker whose testimony was included in the same report—

‘In the city of New York there are places which are known as cruller bakeries, and in these exist some of the worst evils I have ever seen of child labor. The whole place is one mass of smoke from the heated oil, and I have seen children start for these places to work from 11 to 12 at night till 1 o’clock in the morning, and then work the whole night through, or until 4 o’clock in the morning. And you see children lying upon barrels or about the stoves, and they are children from thirteen years old down to nine.’” (New York Bureau of Statistics of Labor Report for 1884, p. 155, quoted in Kelley, Our Toiling Children, p. 24)

Those who worked in cotton mills faced the prospect of getting “white lung” from breathing cotton dust in high temperatures. This could prove deadly. A Massachusetts mill operative testified in 1881 that “‘a child of a tender age” who “‘goes to work in the mill,’” and constantly breathes its air in “‘a temperature of ninety degrees both winter and summer, …is sure to grow up puny and die early.’” (Bureau of Statistics of Labor of Massachusetts, Report, 1881, quoted in Kelley, Our Toiling Children, pp. 26-27)

When states and local governments did pass laws limiting child labor in factories, industrialists generally conspired to undermine the laws. Opponents of child labor regulations made sure that the legislation often contained no funding or mechanisms for enforcement. As a result, these early laws had little if any effect on child labor in factories.

When states tried to enforce minimum age laws by hiring factory inspectors, industrialists—with the help of parents and even children themselves—often engaged in subterfuge. Sometimes, as Wald shows, this subterfuge had an almost slapstick nature–

One mill owner greeted the government inspectors most cordially and, to show his patriotism, ordered the flag to be raised above the works. The raising of the flag, as it afterwards transpired, was a signal to the children employed in the mill to go home. In the early days of child labor reform in New York the children on Henry Street would sometimes relate vividly their experience of being suddenly whisked out of sight when the approach of the factory inspector was signaled.” (Wald, House on Henry Street, p. 145-146)

Writing in 1892, Jacob Riis admitted that reformers had achieved some success in legislating against the worst child labor abuses. Yet he also acknowledged that the existence of laws did not necessarily mean that they would be enforced. “Here in New York,” he wrote, “…we have compulsory education and a factory law prohibiting the employment of young children.” All children between the ages of “eight and fourteen years” were required to attend “school at least fourteen weeks in each year.” No one could “labor in factories under the age of fourteen,” while no one under sixteen was allowed to do factory work “unless able to read and write simple sentences in English.”

Riis and fellow reformers sent “half a dozen factory inspectors” to canvass “more than twice as many thousand workshops.” The inspectors not only found gross violations. They could do little to enforce the law. The great majority of underage children working lied to them and stayed on the job. Since the states did not yet generally record births, there was little reformers could do to disprove the lies. Even those whom they succeeded in turning away returned the “next day to that or some other shop.” (Riis, Children of the Poor, pp. 92-93)

Children themselves often collaborated in breaking laws that were meant to protect them. Once states passed minimum age laws, they learned to routinely and automatically lie about their age. Riis conceded that “The habit of saying fourteen or sixteen” in answer to questions about their age “becomes an unconscious one….” (Riis, Children of the Poor, p. 96) In “seven back-yard factories,” he witnessed “a total of 63 children, of whom 5 admitted being under age, while of the rest 45 seemed surely so. To the other 13 we gave the benefit of the doubt, but I do not think they deserved it.” (Riis, Children of the Poor, p. 95) In one instance, he found a “girl, who could not have been twelve years old…hard at work at a sewing-machine in a Division Street shirt factory….” The “moment she saw” Riis and his colleagues, she “got up and ran.” They soon caught up with her “in the next room hiding behind a pile of shirts,” yet when they confronted her, the girl “said at once that” not only was she “fourteen years old;” she didn’t even “work there….” (Riis, Children of the Poor, p. 96)

Riis made it a mission to visit “a number of factories, in a few instances accompanied by the deputy factory inspector,” but “more frequently alone.” At one location, he “found boys at work, posing as seventeen, who had been” recorded as the same age in the same shop for “three full years, and were thirteen at most.” Some of these boys “were working at power-presses and doing other work beyond their years.” Riis wryly commented that if they were truly seventeen-years old, they could “have made more money in a dime museum” as “freaks” than “at the work-bench.” (Riis, Children of the Poor, pp. 102-103)

Even though many disapproved of children working in factories, whole communities often ignored the reality rather than confronting it. Florence Kelley asserted that the underlying reason for this wholesale refusal to act was economic. Factory owners did not want to relinquish the benefit of paying lower wages to children. Parents coached their offspring to lie to inspectors because they needed the money. And community leaders were fearful that the absence of wage-earning children might result in higher taxes, more spending for schools, and a greater need for philanthropy. (Kelley, Ethical Gains…., pp. 58, 61, 63-64)

By the time Wald moved to the Lower East Side, reformers had made some inroads against child labor in factories. But the practice persisted. Fortunately, so did the efforts of reformers—including Wald.

Bibliography

Adler, Cyrus, Jacob H. Schiff: His Life and Letters, Garden City, NY: Doubleday, Doran and Co., Inc., 1929, vols. I & II.

Blumberg, Dorothy Rose, Florence Kelley: The Making of a Social Pioneer, New York: Augustus M. Kelley, 1966, pp. 99-105.

Bradbury, Dorothy E., Four Decades of Action for Children; A Short History Of The Children’s Bureau, Dorothy E. Bradbury, Assistant Director, Division Of Reports, Children’s Bureau, To the Future, Martha M. Eliot, M.D., Chief Children’s Bureau; U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, Social Security Administration • Children’s Bureau, For Sale By The Superintendent Of Documents, U. S. Government Printing Office, Washington 25, D. C. – Price 35 Cents., 1956

Carson, Mina, Settlement Folk: Social Thought and the American Settlement Movement, 1885-1930, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1990

Daniels, Doris Groshen, Always a Sister: The Feminism of Lillian D. Wald, New York, Feminist Press, 1989

Davis, Allen F., Spearheads for Reform: The Social Settlements and the Progressive Movement, 1890-1914, New York, Oxford University Press, 1967

Duffus, R.L., Lillian Wald: Neighbor and Crusader, New York: The Macmillan Company, 1939

Goldmark, Josephine, Impatient Crusader: Florence Kelley’s Life Story, Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1953

Kelley, Florence, Some Ethical Gains Through Legislation, by Florence Kelley, New York: The Macmillan Company, 1905, pp. 58, 61, 61, 63-64)

[Kelley] Wischnewetzky, Florence Kelley, Our Toiling Children, Chicago, Women’s Temperance Publication Association, 1889, pp. 4-7, 10, 17-18, quoting New York Bureau of Statistics of Labor Report for 1884, pp.155,181, p. 24, quoting Bureau of Statistics of Labor of Massachusetts, Report, 1881, pp. 26-27.

Lubove, Roy, The Progressives and the Slums: Tenement House Reform in New York City, 1890-1917, np: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1962.

Riis, Jacob, The Children of the Poor, New York, Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1908 (c1892), pp. 92-93, 95, 96, 102-103.

Trattner, Walter I., Crusade for the Children: A History of the National Child Labor Committee and Child Labor Reform in America, Chicago: Quadrangle Books, 1970.

Wald, Lillian D., The House on Henry Street, NY: Henry Holt & Co., 1915, pp. 145-146.

Wald, Lillian D., Windows on Henry Street, Boston: Little Brown, and Company, 1934.

Illustrations

The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Photography Collection, The New York Public Library. “Cold Spring.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1875. Link to Illustration Current 12/18/19

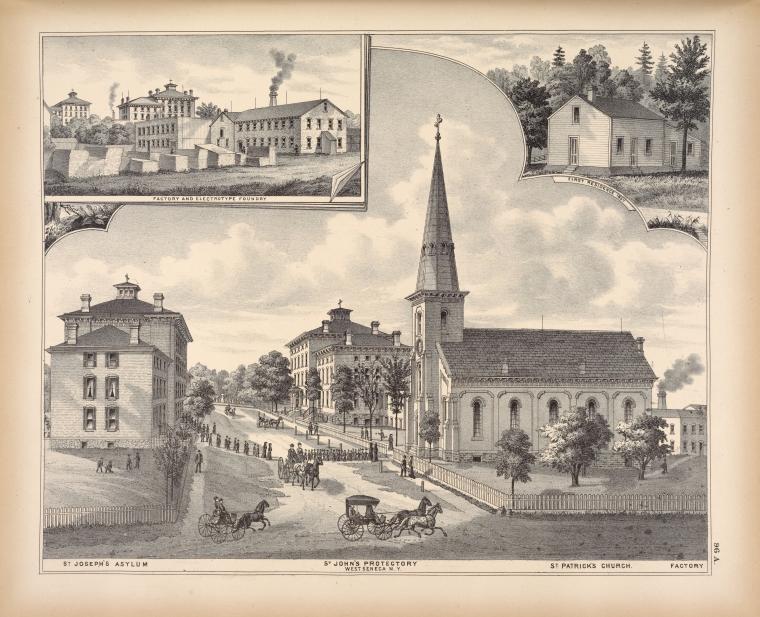

Lionel Pincus and Princess Firyal Map Division, The New York Public Library. “Factory and Electrotype Foundry ; First Residence 1857; St. Joseph’s Asylum, St. John’s Protectory West Seneca, N.Y., St. Patrick’s Church. , Factory” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1880. Link to Illustration Current 12/18/19

Girls Sew Link to Illustration Current 12/10/19

Kelley, Florence, Portrait, public domain Link to Illustration Current 12/10/19

Kelley, Florence, 1925, Public domain Link to Illustration Current 12/10/19

The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Photography Collection, The New York Public Library. “General View Sewing Room — Large Shoe Factory, Syracuse, N.Y.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1895. Link to Illustration Current 12/18/19

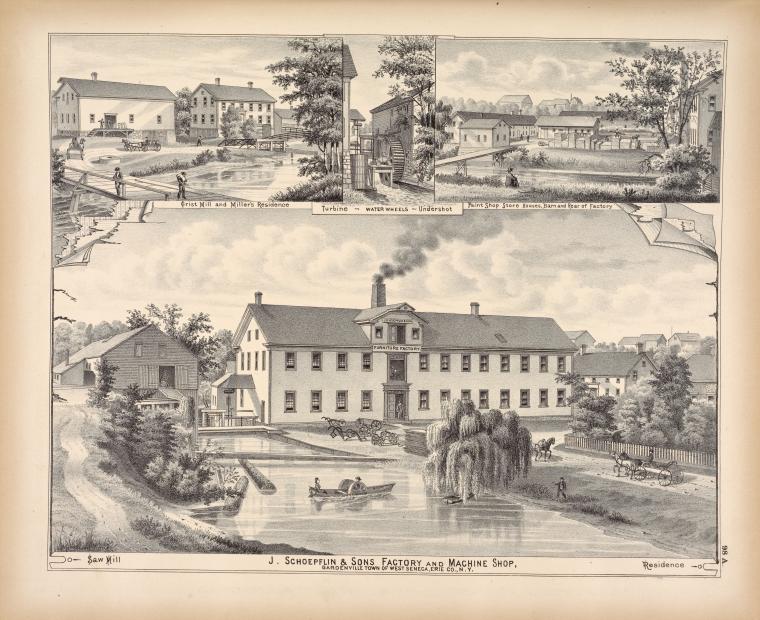

Lionel Pincus and Princess Firyal Map Division, The New York Public Library. “Grist Mill and Miller’s Residence , Turbine – Water Wheels – Undershot, Paint Shop Store Houses, Barn and Rear of Factory; Saw Mill, J. Schoepflin & Sons Factory and Machine Shop, Gardenville town of West Seneca, Erie Co., N.Y.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1880. Link to Illustration Current 12/18/19

The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Photography Collection, The New York Public Library. “Interior of a Factory.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1870. Link to Illustration Current 12/18/19

The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Picture Collection, The New York Public Library. “New York City–destruction by fire of Hale’s piano factory, on West Thirty-fifth Street, September 3d.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1877-09-22. Link to Illustration Current 12/18/19

Lionel Pincus and Princess Firyal Map Division, The New York Public Library. “P.K. Kennedy’s Peddling Wagon & Cigar & Tobacco Factory No. 5 Exchange St. Auburn, New York” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1875. Link to Illustration Current 12/18/19

Riis, Jacob, Portrait(s) Jacob Riis, American journalist. Pirie MacDonald – This image is available from the United States Library of Congress’s Prints and Photographs division under the digital ID cph.3b05563. This tag does not indicate the copyright status of the attached work. A normal copyright tag is still required. See Commons: Licensing for more information. Public Domain File:Jacob Riis 2.jpg Created: 31 December 1905

Link to Illustration Current 12/10/19

The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Picture Collection, The New York Public Library. “Sausage Factory On The East Side ; Habib Assi The Syrian Chef ; Where The Polish Jews Do Their Shopping.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1900. Link to Illustration Current 12/18/19

Shearman, James A., artist. [View of B.T. Babbitt’s “best soap” factory buildings, New York City] [graphic] / J.A. Shearman. Published/Created between 1870 and 1880] Link to Illustration Current 12/18/19

A sweatshop in the United States c.1890 Link to Illustration Current 12/10/19

Copyright Anne M. Filiaci 2021